15.3 Using the Model

Let’s now use the dynamic AD–AS model to analyze how the economy responds to changes in the exogenous variables. The four exogenous variables in the model are the natural level of output  , the supply shock υt, the demand shock εt, and the central bank’s inflation target

, the supply shock υt, the demand shock εt, and the central bank’s inflation target  . To keep things simple, we assume that the economy always begins in long-run equilibrium and is then subject to a change in one of the exogenous variables. We also assume that the other exogenous variables are held constant.

. To keep things simple, we assume that the economy always begins in long-run equilibrium and is then subject to a change in one of the exogenous variables. We also assume that the other exogenous variables are held constant.

Long-Run Growth

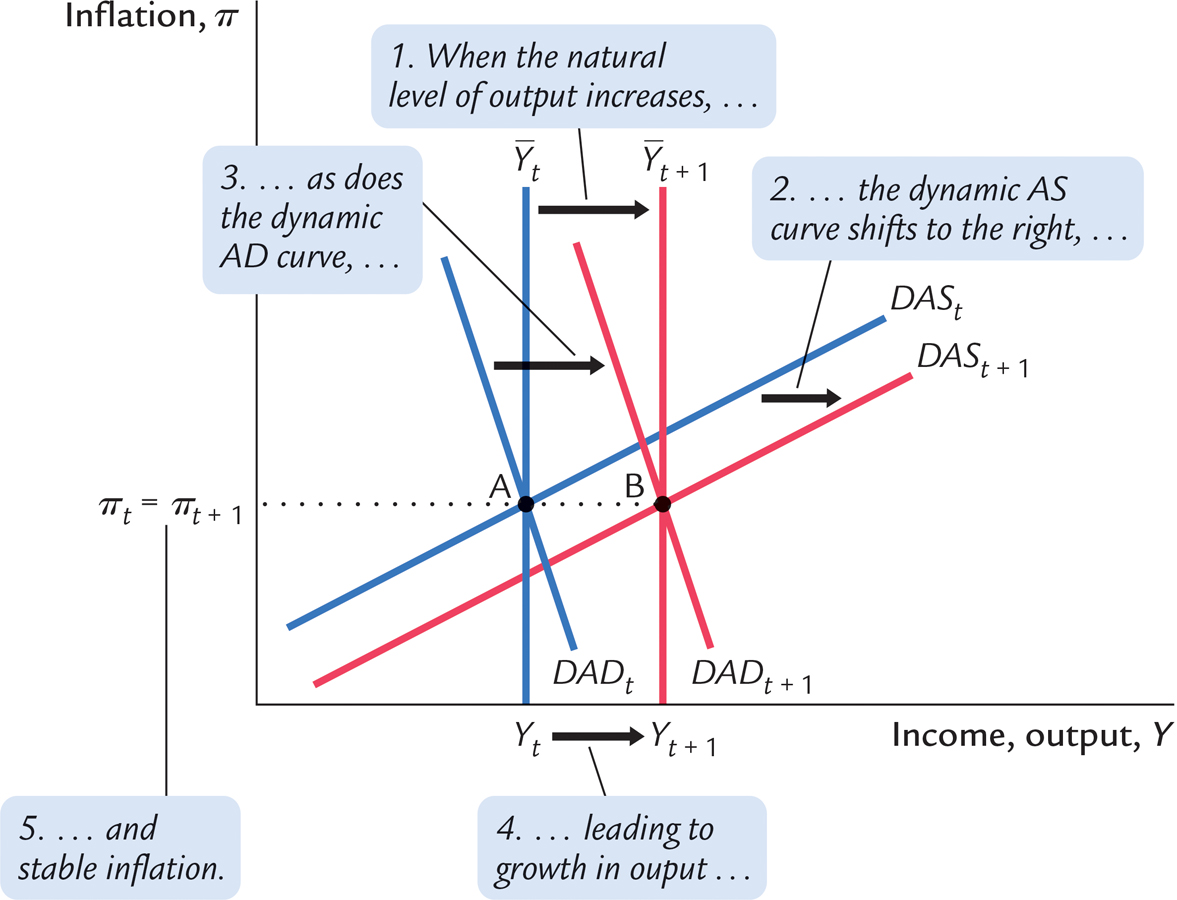

The economy’s natural level of output  grows over time because of population growth, capital accumulation, and technological progress, as discussed in Chapter 8 and Chapter 9. For our purposes here, we can take such growth as exogenous—that is, determined outside of this model. Figure 15-5 illustrates the effect of an exogenous increase in

grows over time because of population growth, capital accumulation, and technological progress, as discussed in Chapter 8 and Chapter 9. For our purposes here, we can take such growth as exogenous—that is, determined outside of this model. Figure 15-5 illustrates the effect of an exogenous increase in  . Because the natural level of output affects both the dynamic aggregate demand curve and the dynamic aggregate supply curve, both curves shift. In fact, they both shift to the right by exactly the amount that

. Because the natural level of output affects both the dynamic aggregate demand curve and the dynamic aggregate supply curve, both curves shift. In fact, they both shift to the right by exactly the amount that  has increased.

has increased.

to increase, both the dynamic aggregate demand curve and the dynamic aggregate supply curve shift to the right by the same amount. Output Yt increases, but inflation πt remains the same.

to increase, both the dynamic aggregate demand curve and the dynamic aggregate supply curve shift to the right by the same amount. Output Yt increases, but inflation πt remains the same.

The shifts in these curves move the economy’s equilibrium in the figure from point A to point B. Output Yt increases by exactly as much as the natural level  . Inflation is unchanged.

. Inflation is unchanged.

The story behind these conclusions is as follows: When the natural level of output increases, the economy can produce a larger quantity of goods and services. This is represented by the rightward shift in the dynamic aggregate supply curve. At the same time, the increase in the natural level of output makes people richer. Other things equal, they want to buy more goods and services. This is represented by the rightward shift in the dynamic aggregate demand curve. The simultaneous shifts in supply and demand increase the economy’s output without putting either upward or downward pressure on inflation. In this way, the economy can experience long-run growth and a stable inflation rate.

455

A Shock to Aggregate Supply

Consider now a shock to aggregate supply. In particular, suppose that υt rises to 1 percent for one period and subsequently returns to zero. This shock to the Phillips curve might occur, for example, because turmoil in the Middle East pushes up world oil prices or because new union agreements raise wages and, thereby, the costs of production. In general, the supply shock υt captures any event that influences inflation other than expected inflation Et−1πt and current economic activity, as measured by  .

.

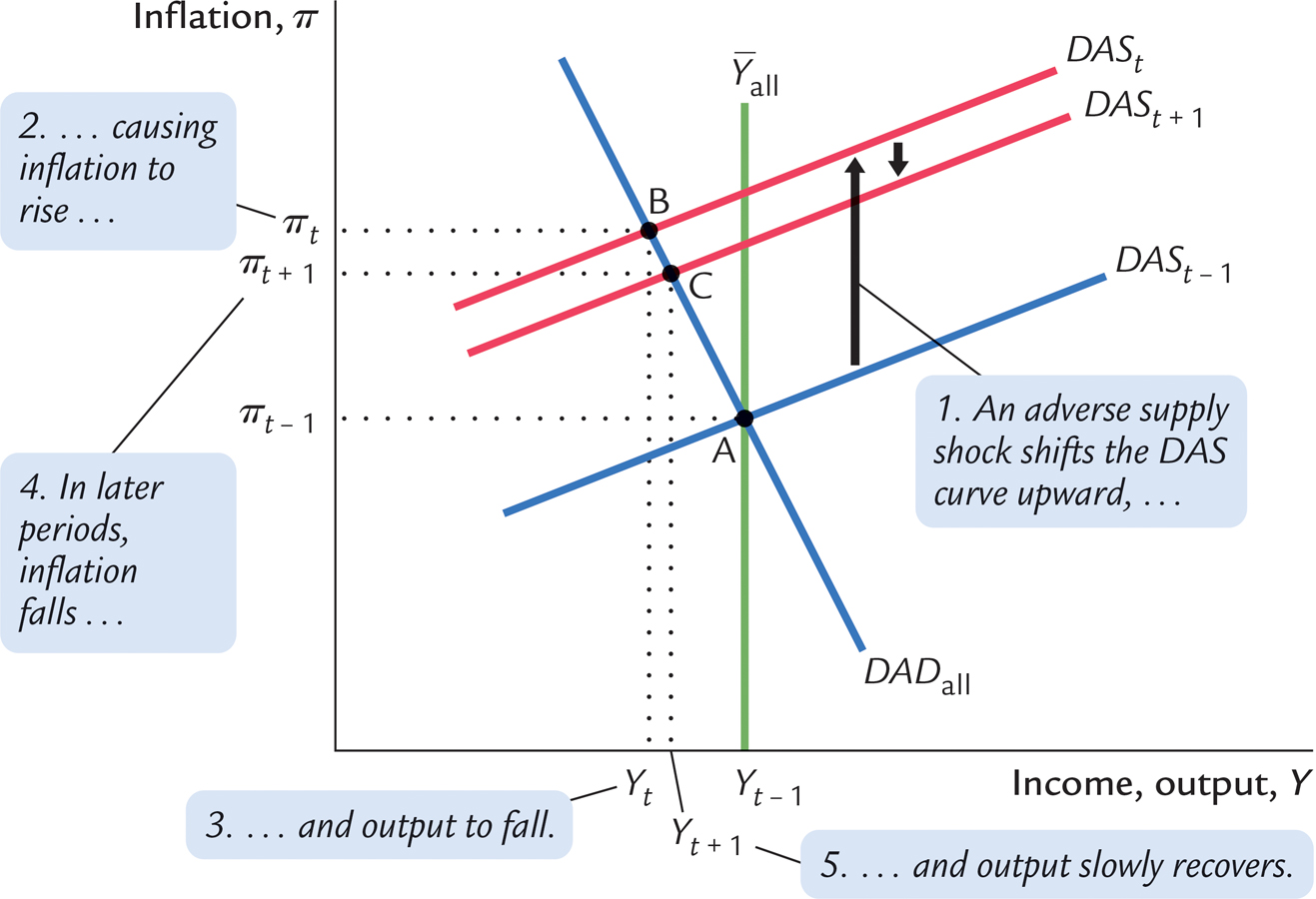

Figure 15-6 shows the result. In period t, when the shock occurs, the dynamic aggregate supply curve shifts upward from DASt−1 to DASt. To be precise, the curve shifts upward by exactly the size of the shock, which we assumed to be 1 percentage point. Because the supply shock υt is not a variable in the dynamic aggregate demand equation, the DAD curve is unchanged. Therefore, the economy moves along the dynamic aggregate demand curve from point A to point B. As the figure illustrates, the supply shock in period t causes inflation to rise to πt and output to fall to Yt.

456

These effects work in part through the reaction of monetary policy to the shock. When the supply shock causes inflation to rise, the central bank responds by following its policy rule and raising nominal and real interest rates. The higher real interest rate reduces the quantity of goods and services demanded, which depresses output below its natural level. (This series of events is represented by the movement along the DAD curve from point A to point B.) The lower level of output dampens the inflationary pressure to some degree, so inflation rises somewhat less than the initial shock.

In the periods after the shock occurs, expected inflation is higher because expectations depend on past inflation. In period t + 1, for instance, the economy is at point C. Even though the shock variable υt returns to its normal value of zero, the dynamic aggregate supply curve does not immediately return to its initial position. Instead, it slowly shifts back downward toward its initial position DASt−1 as a lower level of economic activity reduces inflation and thereby expectations of future inflation. Eventually, the economy finds itself back at point A. Throughout the transition process, however, output remains below its natural level.

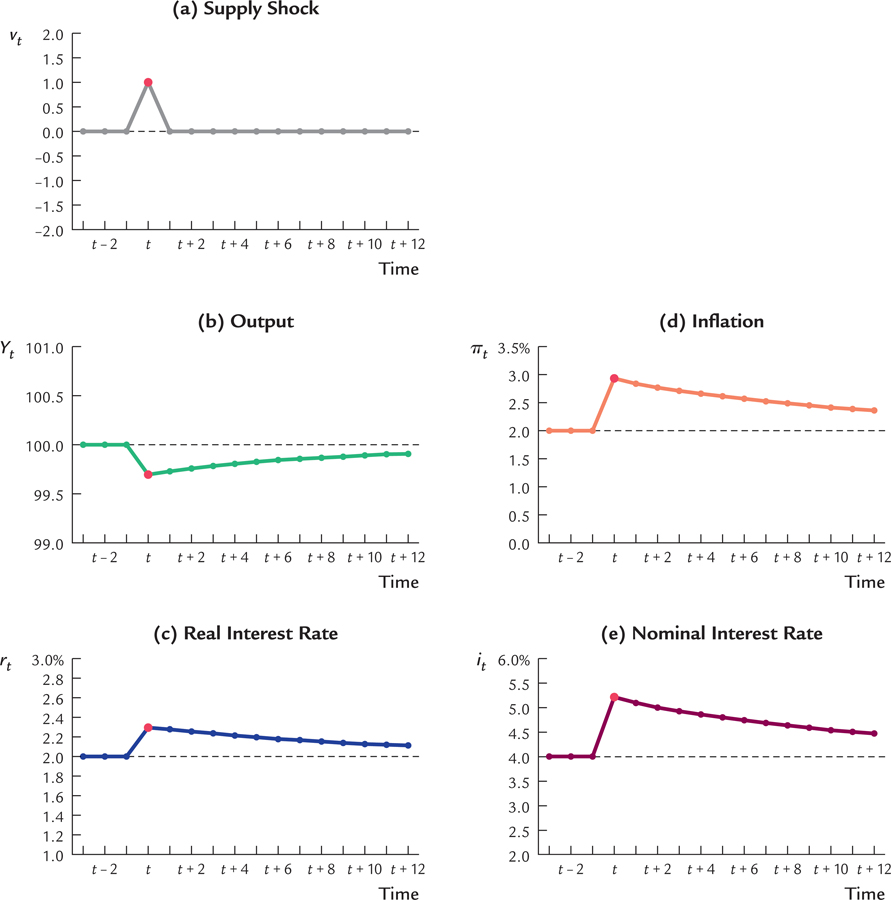

As the economy responds to the supply shock by moving in Figure 15-6 from point A to B to C and then gradually back to point A, all the variables in the model respond accordingly. Figure 15-7 shows the time paths of the key variables. (These simulations are based on realistic parameter values: see the nearby FYI box for their description.) As panel (a) shows, the shock υt spikes upward by 1 percentage point in period t and then returns to zero in subsequent periods. Inflation, shown in panel (d), rises by 0.9 percentage point and slowly returns to its target of 2 percent over a long period of time. Output, shown in panel (b), falls in response to the supply shock but also gradually returns to its natural level.

457

Figure 15-7 also shows the paths of nominal and real interest rates. In the period of the supply shock, the nominal interest rate, shown in panel (e), increases by 1.2 percentage points, and the real interest rate, in panel (c), increases by 0.3 percentage point. Both interest rates return to their normal values as the economy returns to its long-run equilibrium.

458

These figures illustrate the phenomenon of stagflation in the dynamic AD–AS model. A supply shock causes inflation to rise, which in turn increases expected inflation. As the central bank applies its rule for monetary policy and responds by raising interest rates, it gradually squeezes inflation out of the system, but only at the cost of a prolonged downturn in economic activity.

A Shock to Aggregate Demand

Now let’s consider a shock to aggregate demand. To be realistic, the shock is assumed to persist over several periods. In particular, suppose that εt = 1 for five periods and then returns to its normal value of zero. This positive shock εt might represent, for example, a war that increases government purchases or a stock market bubble that increases wealth and thereby consumption spending. In general, the demand shock captures any event that influences the demand for goods and services for given values of the natural level of output  and the real interest rate rt.

and the real interest rate rt.

FYI

The Numerical Calibration and Simulation

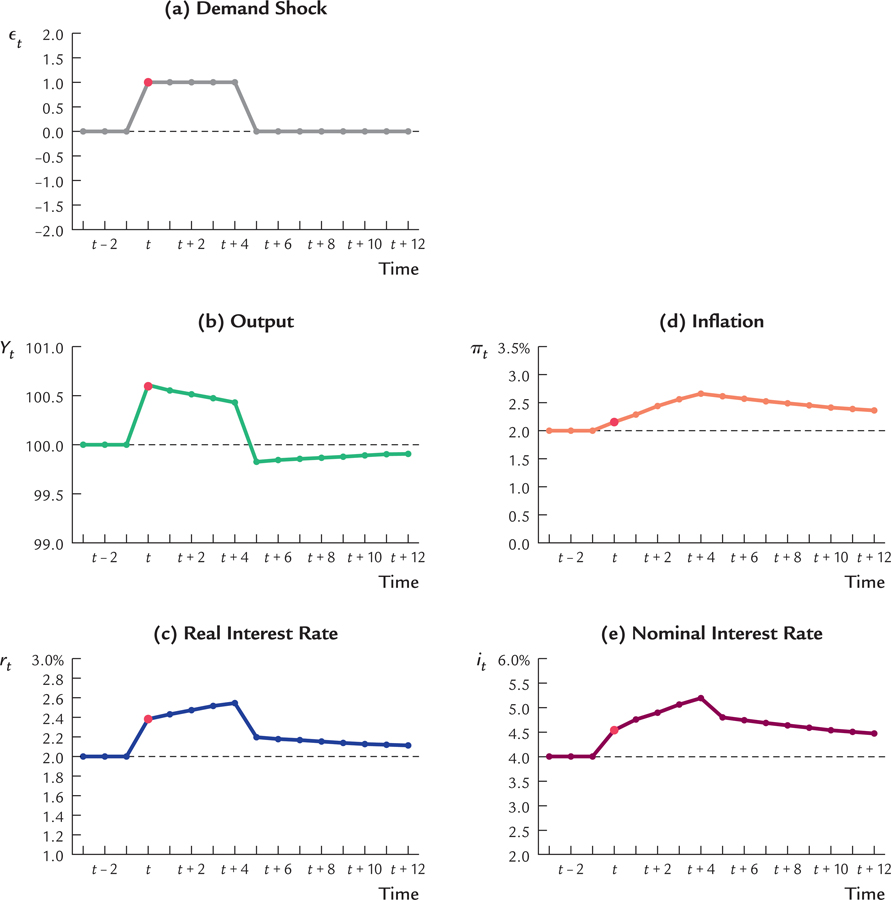

The text presents some numerical simulations of the dynamic AD–AS model. When interpreting these results, it is easiest to think of each period as representing one year. We examine the impact of the change in the year of the shock (period t) and over the subsequent 12 years.

The simulations use these parameter values:

Here is how to interpret these numbers. The natural level of output  is 100; as a result of choosing this convenient number, fluctuations in Yt −

is 100; as a result of choosing this convenient number, fluctuations in Yt −  can be viewed as percentage deviations of output from its natural level. The central bank’s inflation target

can be viewed as percentage deviations of output from its natural level. The central bank’s inflation target  is 2 percent. The parameter α = 1.0 implies that a 1-percentage-point increase in the real interest rate reduces output demand by 1, which is 1 percent of its natural level. The economy’s natural rate of interest ρ is 2 percent. The Phillips curve parameter ϕ = 0.25 implies that when output is 1 percent above its natural level, inflation rises by 0.25 percentage point. The parameters for the monetary policy rule θπ = 0.5 and θY = 0.5 are those suggested by John Taylor and are reasonable approximations of the Federal Reserve’s behavior.

is 2 percent. The parameter α = 1.0 implies that a 1-percentage-point increase in the real interest rate reduces output demand by 1, which is 1 percent of its natural level. The economy’s natural rate of interest ρ is 2 percent. The Phillips curve parameter ϕ = 0.25 implies that when output is 1 percent above its natural level, inflation rises by 0.25 percentage point. The parameters for the monetary policy rule θπ = 0.5 and θY = 0.5 are those suggested by John Taylor and are reasonable approximations of the Federal Reserve’s behavior.

In all cases, the simulations assume a change of 1 percentage point in the exogenous variable of interest. Larger shocks would have qualitatively similar effects, but the magnitudes would be proportionately greater. For example, a shock of 3 percentage points would affect all the variables in the same way as a shock of 1 percentage point, but the movements would be three times as large as those in the simulation shown.

The graphs of the time paths of the variables after a shock (shown in Figure 15-7, Figure 15-9, and Figure 15-11) are called impulse response functions. The word “impulse” refers to the shock, and “response function” refers to how the endogenous variables respond to the shock over time. These simulated impulse response functions are one way to illustrate how the model works. They show how the endogenous variables move when a shock hits the economy, how these variables adjust in subsequent periods, and how they are correlated with one another over time.

459

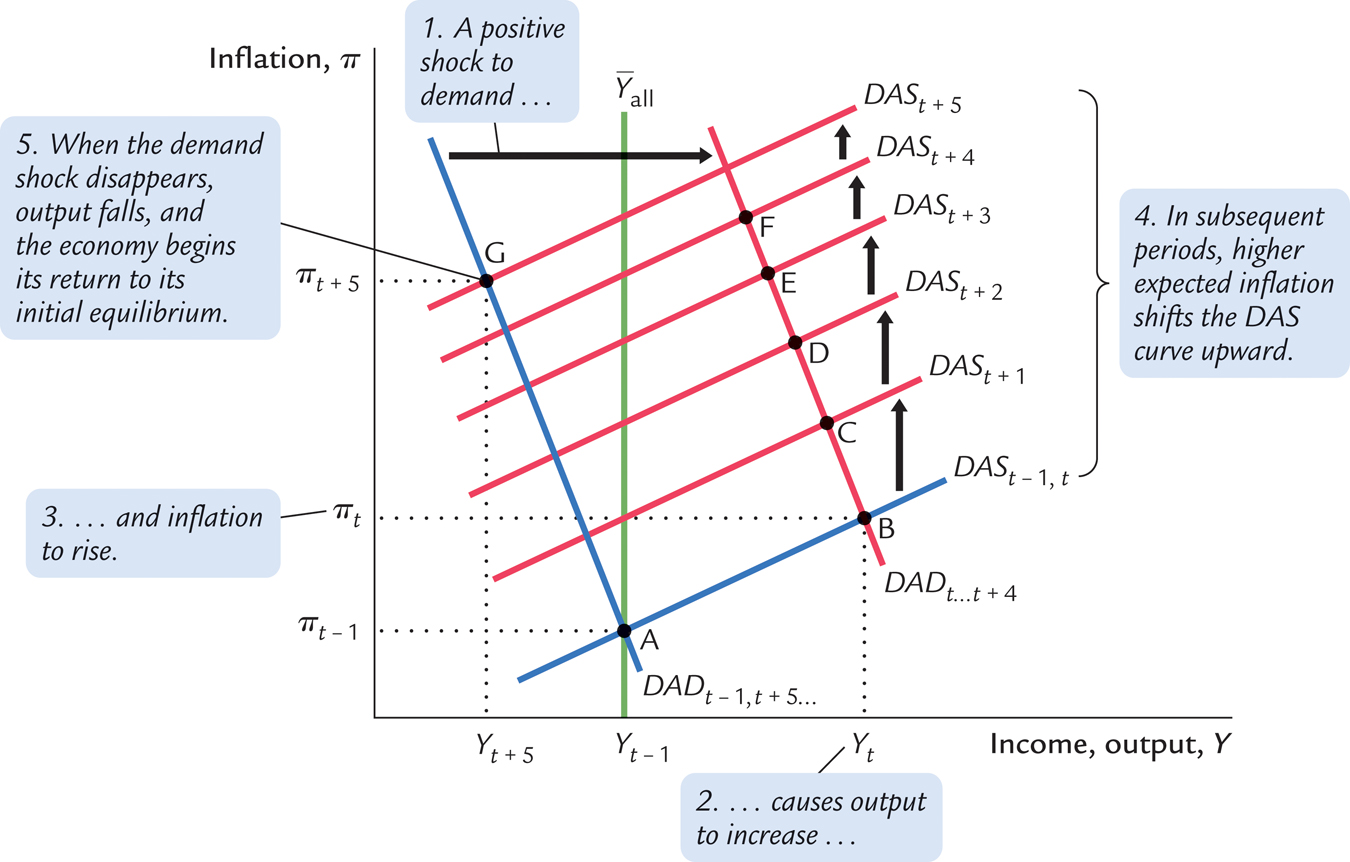

Figure 15-8 shows the result. In period t, when the shock occurs, the dynamic aggregate demand curve shifts to the right from DADt−1 to DADt. Because the demand shock εt is not a variable in the dynamic aggregate supply equation, the DAS curve is unchanged from period t − 1 to period t. The economy moves along the dynamic aggregate supply curve from point A to point B. Output and inflation both increase.

Once again, these effects work in part through the reaction of monetary policy to the shock. When the demand shock causes output and inflation to rise, the central bank responds by increasing the nominal and real interest rates. Because a higher real interest rate reduces the quantity of goods and services demanded, it partly offsets the expansionary effects of the demand shock.

460

In the periods after the shock occurs, expected inflation is higher because expectations depend on past inflation. As a result, the dynamic aggregate supply curve shifts upward repeatedly; as it does so, it continually reduces output and increases inflation. In the figure, the economy goes from point B in the initial period of the shock to points C, D, E, and F in subsequent periods.

In the sixth period (t + 5), the demand shock disappears. At this time, the dynamic aggregate demand curve returns to its initial position. However, the economy does not immediately return to its initial equilibrium, point A. The period of high demand has increased inflation and thereby expected inflation. High expected inflation keeps the dynamic aggregate supply curve higher than it was initially. As a result, when demand falls off, the economy’s equilibrium moves to point G, and output falls to Yt+5, which is below its natural level. The economy then gradually recovers, as the low level of output squeezes the higher-than-target inflation out of the system. Over time, as inflation and expected inflation fall, the economy slowly returns to point A.

Figure 15-9 shows the time path of the key variables in the model in response to the demand shock. Note that the positive demand shock increases real and nominal interest rates. When the demand shock disappears, both interest rates fall. These responses occur because when the central bank sets the nominal interest rate, it takes into account both inflation rates and deviations of output from its natural level.

A Shift in Monetary Policy

Suppose that the central bank decides to reduce its target for the inflation rate. Specifically, imagine that, in period t,  falls from 2 percent to 1 percent and thereafter remains at that lower level. Let’s consider how the economy will react to this change in monetary policy.

falls from 2 percent to 1 percent and thereafter remains at that lower level. Let’s consider how the economy will react to this change in monetary policy.

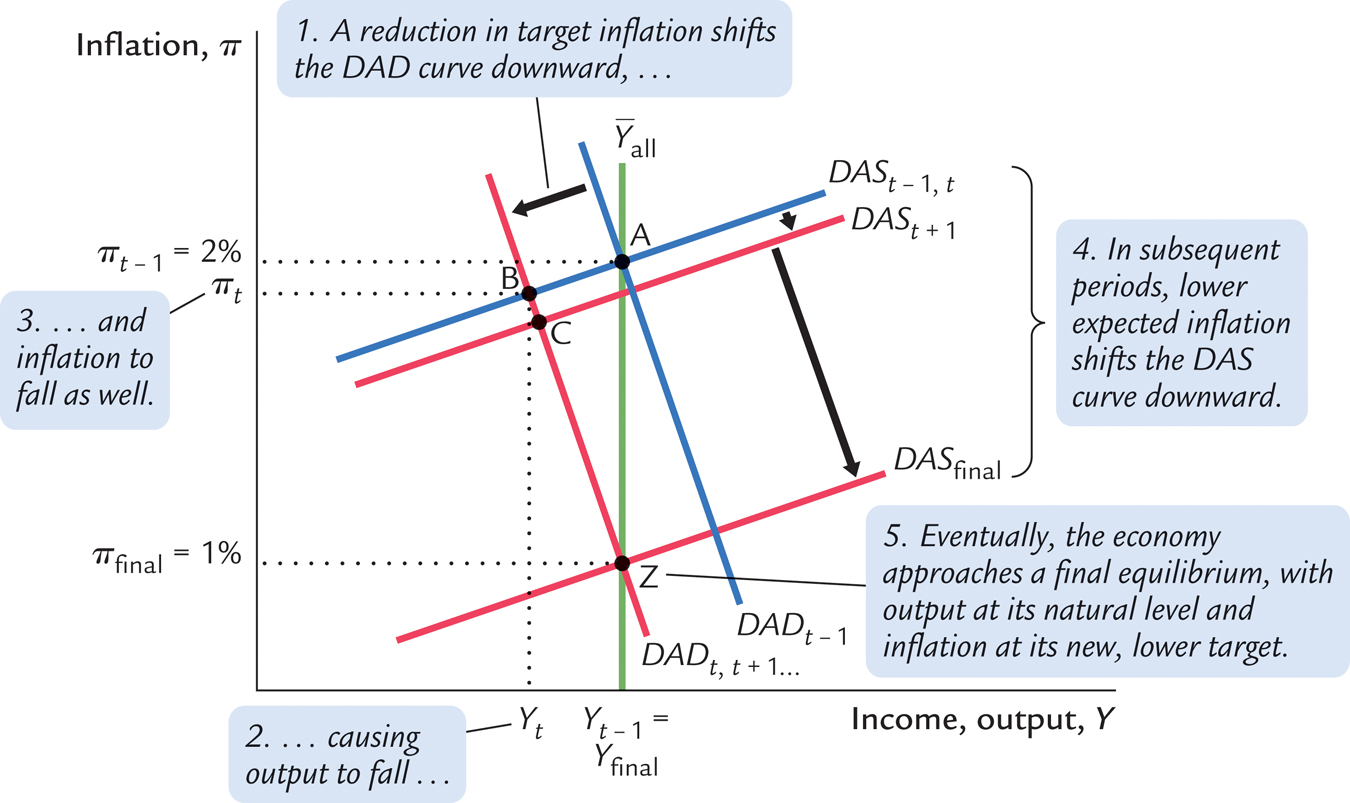

Recall that the inflation target enters the model as an exogenous variable in the dynamic aggregate demand curve. When the inflation target falls, the DAD curve shifts to the left, as shown in Figure 15-10. (To be precise, it shifts downward by exactly 1 percentage point.) Because target inflation does not enter the dynamic aggregate supply equation, the DAS curve does not shift initially. The economy moves from its initial equilibrium, point A, to a new equilibrium, point B. Output falls below its natural level. Inflation falls as well, but not by than the full 1 percentage point by which the central bank has lowered its inflation target.

, and inflation ends at its new, lower target (1 percent).

, and inflation ends at its new, lower target (1 percent).

Monetary policy is, not surprisingly, key to the explanation of this outcome. Because the central bank has just lowered its target for inflation, current inflation is running above the new target. The central bank reacts by following its policy rule and raising real and nominal interest rates. The higher real interest rate reduces the demand for goods and services. The Phillips curve tells us that when output falls, inflation falls as well.

Lower inflation, in turn, reduces the inflation rate that people expect to prevail in the next period. In period t + 1, lower expected inflation shifts the dynamic aggregate supply curve downward, to DASt+1. (To be precise, the curve shifts downward by exactly the fall in expected inflation.) This shift moves the economy from point B to point C, further reducing inflation and expanding output. Over time, as inflation continues to fall toward the new 1 percent target and the DAS curve continues to shift toward DASfinal, the economy approaches a new long-run equilibrium at point Z, where output is back at its natural level (Yfinal =  ) and inflation is at its new lower target (πfinal = 1 percent).

) and inflation is at its new lower target (πfinal = 1 percent).

461

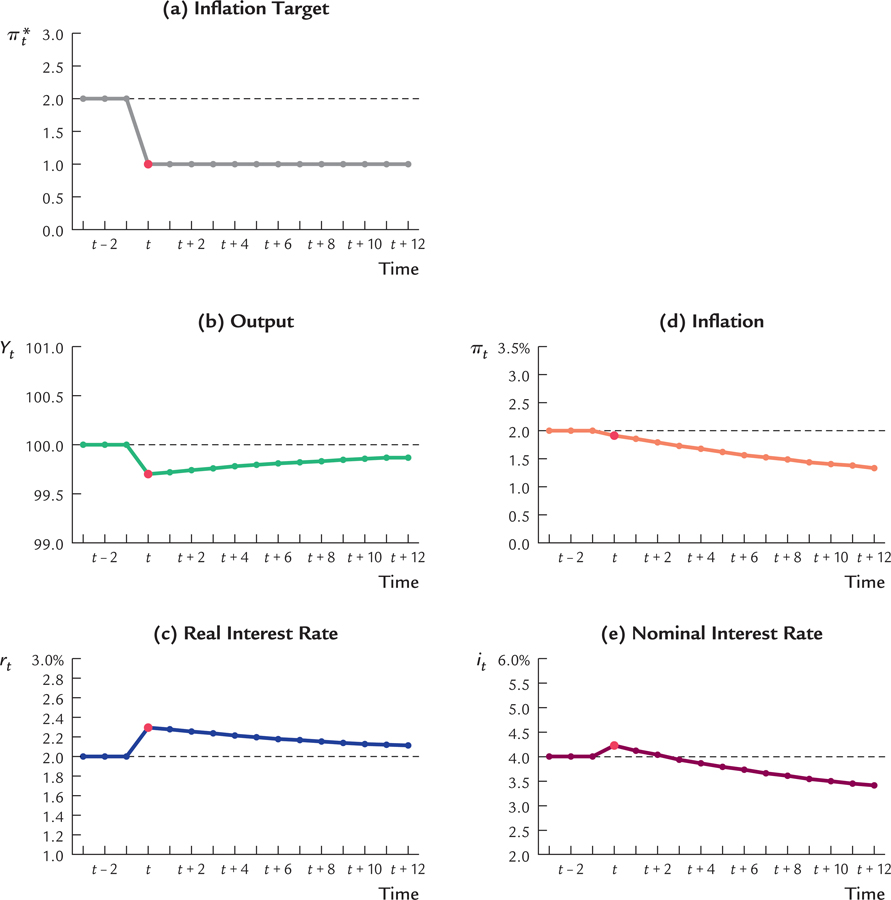

Figure 15-11 shows the response of the variables over time to a reduction in target inflation. Note in panel (e) the time path of the nominal interest rate it. Before the change in policy, the nominal interest rate is at its long-run value of 4.0 percent (which equals the natural real interest rate ρ of 2 percent plus target inflation  of 2 percent). When target inflation falls to 1 percent, the nominal interest rate rises to 4.2 percent. Over time, however, the nominal interest rate falls as inflation and expected inflation fall toward the new target rate; eventually, it approaches its new long-run value of 3.0 percent. Thus, a shift toward a lower inflation target increases the nominal interest rate in the short run but decreases it in the long run.

of 2 percent). When target inflation falls to 1 percent, the nominal interest rate rises to 4.2 percent. Over time, however, the nominal interest rate falls as inflation and expected inflation fall toward the new target rate; eventually, it approaches its new long-run value of 3.0 percent. Thus, a shift toward a lower inflation target increases the nominal interest rate in the short run but decreases it in the long run.

462

We close with a caveat: Throughout this analysis we have maintained the assumption of adaptive expectations. That is, we have assumed that people form their expectations of inflation based on the inflation they have recently experienced. It is possible, however, that if the central bank makes a credible announcement of its new policy of lower target inflation, people will respond by immediately altering their expectations of inflation. That is, they may form expectations rationally, based on the policy announcement, rather than adaptively, based on what they have experienced. (We discussed this possibility in Chapter 14.) If so, the dynamic aggregate supply curve will shift downward immediately upon the change in policy, just when the dynamic aggregate demand curve shifts downward. In this case, the economy will instantly reach its new long-run equilibrium. By contrast, if people do not believe an announced policy of low inflation until they see it, then the assumption of adaptive expectations is appropriate, and the transition path to lower inflation will involve a period of lost output, as shown in Figure 15-11.

463