16.1 John Maynard Keynes and the Consumption Function

We begin our study of consumption with John Maynard Keynes’s General Theory, which was published in 1936. Keynes made the consumption function central to his theory of economic fluctuations, and it has played a key role in macroeconomic analysis ever since. Let’s consider what Keynes thought about the consumption function and then see what puzzles arose when his ideas were confronted with the data.

Keynes’s Conjectures

Today, economists who study consumption rely on sophisticated techniques of data analysis. With the help of computers, they analyze aggregate data on the behavior of the overall economy from the national income accounts and detailed data on the behavior of individual households from surveys. Because Keynes wrote in the 1930s, however, he had neither the advantage of these data nor the computers necessary to analyze such large data sets. Instead of relying on statistical analysis, Keynes made conjectures about the consumption function that were based on introspection and casual observation.

First and most important, Keynes conjectured that the marginal propensity to consume—the amount consumed out of an additional dollar of income—is between zero and one. He wrote that the “fundamental psychological law, upon which we are entitled to depend with great confidence, … is that men are disposed, as a rule and on the average, to increase their consumption as their income increases, but not by as much as the increase in their income.” That is, when a person earns an extra dollar, he typically spends some of it and saves some of it. As we saw in Chapter 11 when we developed the Keynesian cross, the marginal propensity to consume was crucial to Keynes’s policy recommendations for how to reduce widespread unemployment. The power of fiscal policy to influence the economy—as expressed by the fiscal-policy multipliers—arises from the feedback between income and consumption.

Second, Keynes posited that the ratio of consumption to income, called the average propensity to consume, falls as income rises. He believed that saving was a luxury, so he expected the rich to save a higher proportion of their income than the poor. Although not essential for Keynes’s own analysis, the postulate that the average propensity to consume falls as income rises became a central part of early Keynesian economics.

Third, Keynes thought that income is the primary determinant of consumption and that the interest rate does not have an important role. This conjecture stood in stark contrast to the beliefs of the classical economists who preceded him. The classical economists held that a higher interest rate encourages saving and discourages consumption. Keynes admitted that the interest rate could influence consumption as a matter of theory. Yet he wrote that “the main conclusion suggested by experience, I think, is that the short-period influence of the rate of interest on individual spending out of a given income is secondary and relatively unimportant.”

477

On the basis of these three conjectures, the Keynesian consumption function is often written as

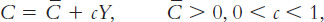

where C is consumption, Y is disposable income,  is a constant, and c is the marginal propensity to consume. This consumption function, shown in Figure 16-1, is graphed as a straight line.

is a constant, and c is the marginal propensity to consume. This consumption function, shown in Figure 16-1, is graphed as a straight line.  determines the intercept on the vertical axis, and c determines the slope.

determines the intercept on the vertical axis, and c determines the slope.

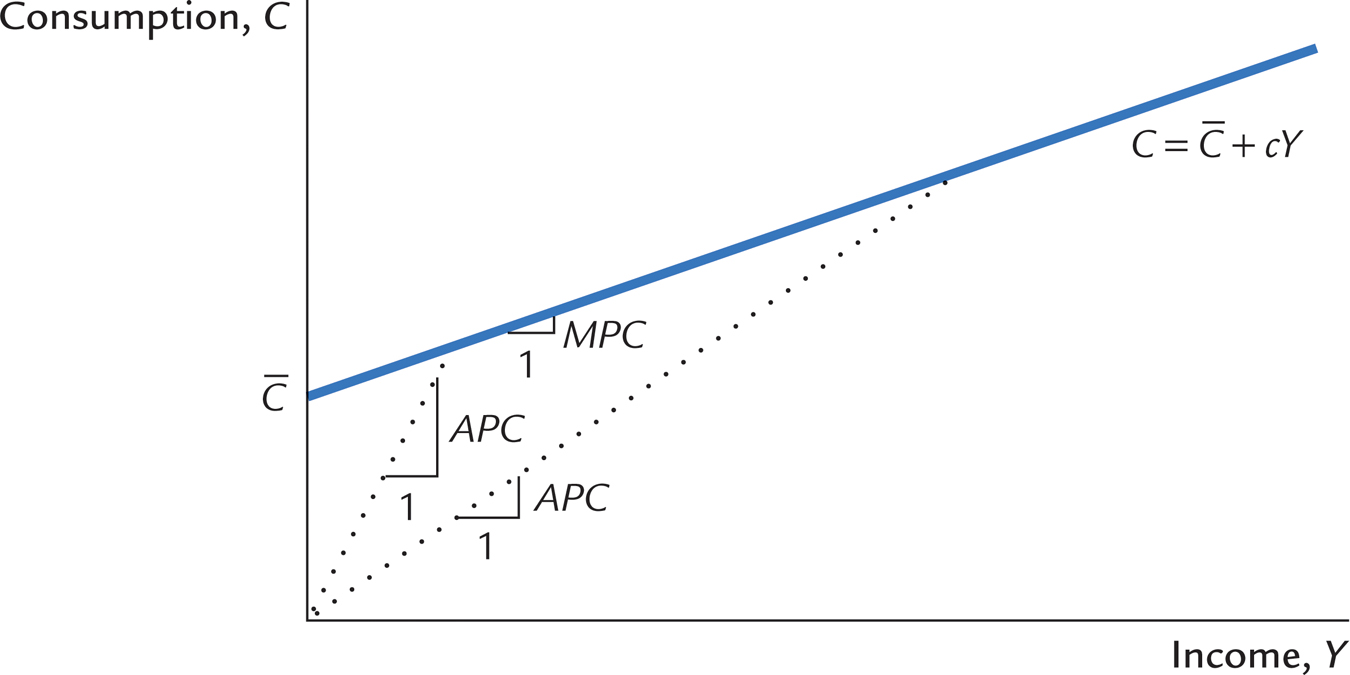

Notice that this consumption function exhibits the three properties that Keynes posited. It satisfies Keynes’s first property because the marginal propensity to consume c is between zero and one, so that higher income leads to higher consumption and also to higher saving. This consumption function satisfies Keynes’s second property because the average propensity to consume APC is

As Y rises,  /Y falls, and so the average propensity to consume C/Y falls. And finally, this consumption function satisfies Keynes’s third property because the interest rate is not included in this equation as a determinant of consumption.

/Y falls, and so the average propensity to consume C/Y falls. And finally, this consumption function satisfies Keynes’s third property because the interest rate is not included in this equation as a determinant of consumption.

The Early Empirical Successes

Soon after Keynes proposed the consumption function, economists began collecting and examining data to test his conjectures. The earliest studies indicated that the Keynesian consumption function was a good approximation of how consumers behave.

In some of these studies, researchers surveyed households and collected data on consumption and income. They found that households with higher income consumed more, which confirms that the marginal propensity to consume is greater than zero. They also found that households with higher income saved more, which confirms that the marginal propensity to consume is less than one. In addition, these researchers found that higher-income households saved a larger fraction of their income, which confirms that the average propensity to consume falls as income rises. Thus, these data verified Keynes’s conjectures about the marginal and average propensities to consume.

478

In other studies, researchers examined aggregate data on consumption and income for the period between the two world wars. These data also supported the Keynesian consumption function. In years when income was unusually low, such as during the depths of the Great Depression, both consumption and saving were low, indicating that the marginal propensity to consume is between zero and one. In addition, during those years of low income, the ratio of consumption to income was high, confirming Keynes’s second conjecture. Finally, because the correlation between income and consumption was so strong, no other variable appeared to be important for explaining consumption. Thus, the data also confirmed Keynes’s third conjecture that income is the primary determinant of how much people choose to consume.

Secular Stagnation, Simon Kuznets, and the Consumption Puzzle

Although the Keynesian consumption function met with early successes, two anomalies soon arose. Both concern Keynes’s conjecture that the average propensity to consume falls as income rises.

The first anomaly became apparent after some economists made a dire—and, it turned out, erroneous—prediction during World War II. On the basis of the Keynesian consumption function, these economists reasoned that as incomes in the economy grew over time, households would consume a smaller and smaller fraction of their incomes. They feared that there might not be enough profitable investment projects to absorb all this saving. If so, the low consumption would lead to an inadequate demand for goods and services, resulting in a depression once the wartime demand from the government ceased. In other words, on the basis of the Keynesian consumption function, these economists predicted that the economy would experience what they called secular stagnation—a long depression of indefinite duration—unless the government used fiscal policy to expand aggregate demand.

Fortunately for the economy, but unfortunately for the Keynesian consumption function, the end of World War II did not throw the country into another depression. Although incomes were much higher after the war than before, these higher incomes did not lead to large increases in the rate of saving. Keynes’s conjecture that the average propensity to consume would fall as income rose appeared not to hold.

The second anomaly arose when economist Simon Kuznets constructed new aggregate data on consumption and income dating back to 1869. Kuznets assembled these data in the 1940s and would later receive the Nobel Prize for this work. He discovered that the ratio of consumption to income was remarkably stable from decade to decade, despite large increases in income over the period he studied. Again, Keynes’s conjecture that the average propensity to consume would fall as income rose appeared not to hold.

479

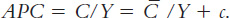

The failure of the secular-stagnation hypothesis and the findings of Kuznets both indicated that the average propensity to consume is fairly constant over long periods of time. This fact presented a puzzle that motivated much of the subsequent research on consumption. Economists wanted to know why some studies confirmed Keynes’s conjectures and others refuted them. That is, why did Keynes’s conjectures hold up well in the studies of household data and in the studies of short time-series but fail when long time-series were examined?

Figure 16-2 illustrates the puzzle. The evidence suggested that there were two consumption functions. For the household data and for the short time-series, the Keynesian consumption function appeared to work well. Yet for the long time-series, the consumption function appeared to exhibit a constant average propensity to consume. In Figure 16-2, these two relationships between consumption and income are called the short-run and long-run consumption functions. Economists needed to explain how these two consumption functions could be consistent with each other.

In the 1950s, Franco Modigliani and Milton Friedman each proposed explanations of these seemingly contradictory findings. Both economists later won Nobel Prizes, in part because of their work on consumption. But before we see how Modigliani and Friedman tried to solve the consumption puzzle, we must discuss Irving Fisher’s contribution to consumption theory. Both Modigliani’s life-cycle hypothesis and Friedman’s permanent-income hypothesis rely on the theory of consumer behavior proposed much earlier by Irving Fisher.

480