2.3 Measuring Joblessness: The Unemployment Rate

One aspect of economic performance is how well an economy uses its resources. Because an economy’s workers are its chief resource, keeping workers employed is a paramount concern of economic policymakers. The unemployment rate is the statistic that measures the percentage of those people wanting to work who do not have jobs. Every month, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics computes the unemployment rate and many other statistics that economists and policymakers use to monitor developments in the labor market.

The Household Survey

The unemployment rate comes from a survey of about 60,000 households called the Current Population Survey. Based on the responses to survey questions, each adult (age 16 and older) in each household is placed into one of three categories:

Employed. This category includes those who at the time of the survey worked as paid employees, worked in their own business, or worked as unpaid workers in a family member’s business. It also includes those who were not working but who had jobs from which they were temporarily absent because of, for example, vacation, illness, or bad weather.

Unemployed. This category includes those who were not employed, were available for work, and had tried to find employment during the previous four weeks. It also includes those waiting to be recalled to a job from which they had been laid off.

Not in the labor force. This category includes those who fit neither of the first two categories, such as a full-

time student, homemaker, or retiree.

Notice that a person who wants a job but has given up looking—

39

The labor force is the sum of the employed and unemployed, and the unemployment rate is the percentage of the labor force that is unemployed. That is,

Labor Force = Number of Employed + Number of Unemployed

and

A related statistic is the labor-

The Bureau of Labor Statistics computes these statistics for the overall population and for groups within the population: men and women, whites and blacks, teenagers and prime-

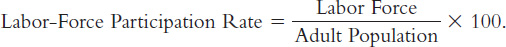

Figure 2-4 shows the breakdown of the population into the three categories for April 2014. The statistics broke down as follows:

Labor Force = 145.7 + 9.7 = 155.4 million.

Unemployment Rate = (9.7/155.4) × 100 = 6.2%.

Labor-

40

Hence, almost two-

CASE STUDY

Men, Women, and Labor-

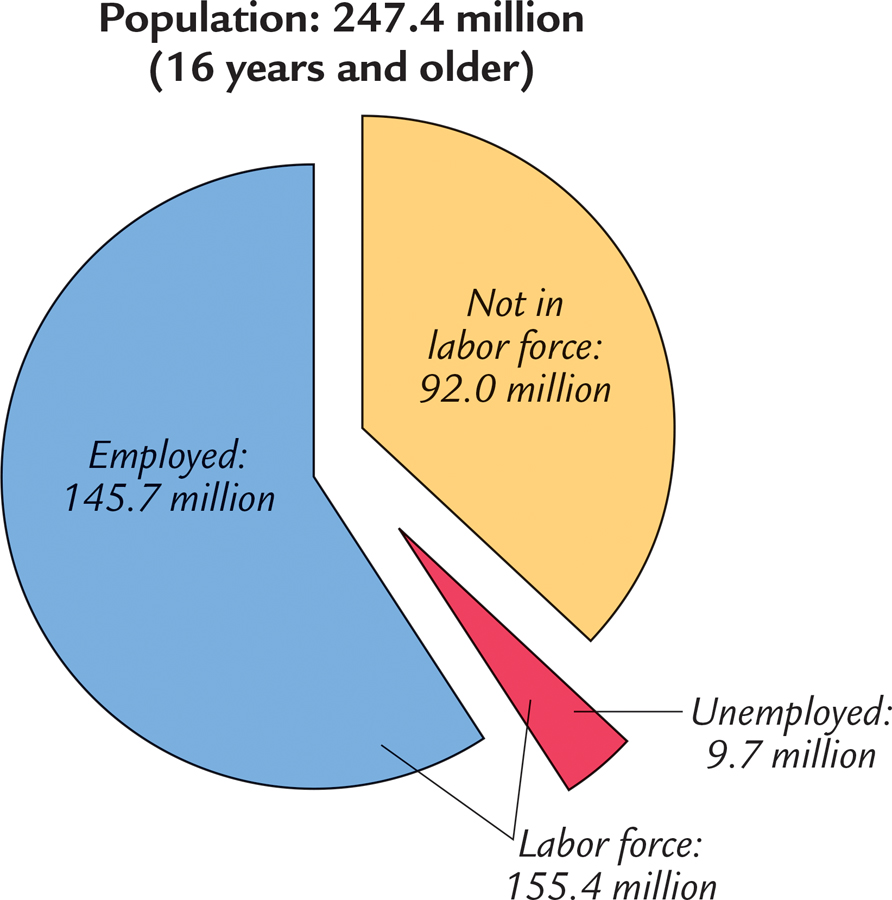

The data on the labor market collected by the Bureau of Labor Statistics reflect not only economic developments, such as the booms and busts of the business cycle, but also a variety of social changes. Longer-

Figure 2-5 shows the labor-

There are many reasons for this change. In part, it is due to new technologies, such as the washing machine, clothes dryer, refrigerator, freezer, and dishwasher, which have reduced the amount of time required to complete routine household tasks. In part, it is due to improved birth control, which has reduced the number of children born to the typical family. And in part, this change in women’s role is due to changing political and social attitudes. Together, these developments have had a profound impact, as demonstrated by these data.

41

Although the increase in women’s labor-

Figure 2-5 shows that, in the most recent decade, the labor-

The Establishment Survey

When the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reports the unemployment rate every month, it also reports a variety of other statistics describing conditions in the labor market. Some of these statistics, such as the labor-

Because the BLS conducts two surveys of labor-

One might expect these two measures of employment to be identical, but that is not the case. Although they are positively correlated, the two measures can diverge, especially over short periods of time. An example of a large divergence occurred in the early 2000s, as the economy recovered from the recession of 2001. From November 2001 to August 2003, the establishment survey showed a decline in employment of 1.0 million, while the household survey showed an increase of 1.4 million. Some commentators said the economy was experiencing a “jobless recovery,” but this description applied only to the establishment data, not to the household data.

Why might these two measures of employment diverge? Part of the explanation is that the surveys measure different things. For example, a person who runs his or her own business is self-

42

Another part of the explanation for the divergence is that surveys are imperfect. For example, when new firms start up, it may take some time before those firms are included in the establishment survey. The BLS tries to estimate employment at start-

In the end, the divergence between the household and establishment surveys from 2001 to 2003 remains a mystery. Some economists believe that the establishment survey is the more accurate one because it has a larger sample. Yet one study suggests that the best measure of employment is an average of the two surveys.6

More important than the specifics of these surveys or this particular episode when they diverged is the broader lesson: all economic statistics are imperfect. Although they contain valuable information about what is happening in the economy, each one should be interpreted with a healthy dose of caution and a bit of skepticism.