4.1 What Is Money?

When we say that a person has a lot of money, we usually mean that he or she is wealthy. By contrast, economists use the term “money” in a more specialized way. To an economist, money does not refer to all wealth but only to one type of it: money is the stock of assets that can be readily used to make transactions. Roughly speaking, the dollars (or, in other countries, for example, pounds or yen) in the hands of the public make up the nation’s stock of money.

The Functions of Money

Money has three purposes: it is a store of value, a unit of account, and a medium of exchange.

As a store of value, money is a way to transfer purchasing power from the present to the future. If I work today and earn $100, I can hold the money and spend it tomorrow, next week, or next month. Money is not a perfect store of value: if prices are rising, the amount you can buy with any given quantity of money is falling. Even so, people hold money because they can trade it for goods and services at some time in the future.

As a unit of account, money provides the terms in which prices are quoted and debts are recorded. Microeconomics teaches us that resources are allocated according to relative prices—

As a medium of exchange, money is what we use to buy goods and services. “This note is legal tender for all debts, public and private” is printed on the U.S. dollar. When we walk into stores, we are confident that the shopkeepers will accept our money in exchange for the items they are selling. The ease with which an asset can be converted into the medium of exchange and used to buy other things—

To better understand the functions of money, try to imagine an economy without it: a barter economy. In such a world, trade requires the double coincidence of wants—the unlikely happenstance of two people each having a good that the other wants at the right time and place to make an exchange. A barter economy permits only simple transactions.

Money makes more indirect transactions possible. A professor uses his salary to buy books; the book publisher uses its revenue from the sale of books to buy paper; the paper company uses its revenue from the sale of paper to buy wood that it grinds into paper pulp; the lumber company uses revenue from the sale of wood to pay the lumberjack; the lumberjack uses his income to send his child to college; and the college uses its tuition receipts to pay the salary of the professor. In a complex, modern economy, trade is usually indirect and requires the use of money.

83

The Types of Money

Money takes many forms. In the U.S. economy we make transactions with an item whose sole function is to act as money: dollar bills. These pieces of green paper with small portraits of famous Americans would have little value if they were not widely accepted as money. Money that has no intrinsic value is called fiat money because it is established as money by government decree, or fiat.

Fiat money is the norm in most economies today, but most societies in the past have used a commodity with some intrinsic value for money. This type of money is called commodity money. The most widespread example is gold. When people use gold as money (or use paper money that is redeemable for gold), the economy is said to be on a gold standard. Gold is a form of commodity money because it can be used for various purposes—

CASE STUDY

Money in a POW Camp

An unusual form of commodity money developed in some Nazi prisoner of war (POW) camps during World War II. The Red Cross supplied the prisoners with various goods—

Barter proved to be an inconvenient way to allocate these resources, however, because it required the double coincidence of wants. In other words, a barter system was not the easiest way to ensure that each prisoner received the goods he valued most. Even the limited economy of the POW camp needed some form of money to facilitate transactions.

Eventually, cigarettes became the established “currency” in which prices were quoted and with which trades were made. A shirt, for example, cost about 80 cigarettes. Services were also quoted in cigarettes: some prisoners offered to do other prisoners’ laundry for two cigarettes per garment. Even nonsmokers were happy to accept cigarettes in exchange, knowing they could trade the cigarettes in the future for some good they did enjoy. Within the POW camp the cigarette became the store of value, the unit of account, and the medium of exchange.1

84

The Development of Fiat Money

It is not surprising that in any society, no matter how primitive, some form of commodity money arises to facilitate exchange: people are willing to accept a commodity currency such as gold because it has intrinsic value. The development of fiat money, however, is more perplexing. What would make people begin to value something that is intrinsically useless?

To understand how the evolution from commodity money to fiat money takes place, imagine an economy in which people carry around bags of gold. When a purchase is made, the buyer measures out the appropriate amount of gold. If the seller is convinced that the weight and purity of the gold are right, the buyer and seller make the exchange.

The government might first get involved in the monetary system to help people reduce transaction costs. Using raw gold as money is costly because it takes time to verify the purity of the gold and to measure the correct quantity. To reduce these costs, the government can mint gold coins of known purity and weight. The coins are easier to use than gold bullion because their values are widely recognized.

The next step is for the government to accept gold from the public in exchange for gold certificates—

Finally, the gold backing becomes irrelevant. If no one ever bothers to redeem the bills for gold, no one cares if the option is abandoned. As long as everyone continues to accept the paper bills in exchange, they will have value and serve as money. Thus, the system of commodity money evolves into a system of fiat money. Notice that in the end the use of money in exchange is a social convention: everyone values fiat money because they expect everyone else to value it.

CASE STUDY

Money and Social Conventions on the Island of Yap

The economy of Yap, a small island in the Pacific, once had a type of money that was something between commodity and fiat money. The traditional medium of exchange in Yap was fei, stone wheels up to 12 feet in diameter. These stones had holes in the center so that they could be carried on poles and used for exchange.

Large stone wheels are not a convenient form of money. The stones were heavy, so it took substantial effort for a new owner to take his fei home after completing a transaction. Although the monetary system facilitated exchange, it did so at great cost.

Eventually, it became common practice for the new owner of the fei not to bother to take physical possession of the stone. Instead, the new owner accepted a claim to the fei without moving it. In future bargains, he traded this claim for goods that he wanted. Having physical possession of the stone became less important than having legal claim to it.

85

This practice was put to a test when a valuable stone was lost at sea during a storm. Because the owner lost his money by accident rather than through negligence, everyone agreed that his claim to the fei remained valid. Generations later, when no one alive had ever seen this stone, the claim to this fei was still valued in exchange.

Even today, stone money is still valued on the island. It is, however, not the medium of exchange used for most routine transactions. For that purpose, the 11,000 current residents of Yap use something a bit more prosaic: the U.S. dollar.2

FYI

Bitcoin: The Strange Case of a Virtual Money

In 2009, the world was introduced to a new and unusual asset, called bitcoin. Conceived by an anonymous computer expert (or group of experts) who goes by the name Satoshi Nakamoto, bitcoin is intended to be a form of money that exists only in electronic form. Individuals originally obtain bitcoins by using computers to solve complex mathematical problems. The bitcoin protocol is designed to limit the number of bitcoins that can ever be “mined” in this way to 21 million units (though experts disagree whether the number of bitcoins is truly limited). After the bitcoins are created, they can be used in exchange. They can be bought and sold for U.S. dollars and other currencies on organized bitcoin exchanges, where the exchange rate is set by supply and demand. You can use bitcoins to buy things from any vendor who is willing to accept them.

As a form of money, bitcoins are neither commodity money nor fiat money. Unlike commodity money, they have no intrinsic value. You can’t use bitcoins for anything other than exchange. Unlike fiat money, they are not created by government decree. Indeed, many fans of bitcoin embrace the fact that this electronic cash exists apart from government (and some users of it are engaged in illicit transactions such as the drug trade). Bitcoins have value only to the extent that people accept the social convention of taking them in exchange. From this perspective, the modern bitcoin resembles the primitive money of Yap.

Throughout its short history, the value of a bitcoin, as measured by its price in U.S. dollars, has fluctuated wildly. On its first day of trading in 2009, the price of a bitcoin was only about 5 cents, and it stayed below 10 cents for the following year. In 2011, the price rose to above $1, and in 2013, it briefly exceeded $1,200, before falling below $500 in 2014. Gold is often considered a risky asset, but the day-

The long-

Advocates of bitcoin see it as the money of the future. Another possibility, however, is that it is a speculative fad that will eventually run its course.3

86

How the Quantity of Money Is Controlled

The quantity of money available in an economy is called the money supply. In a system of commodity money, the money supply is simply the quantity of that commodity. In an economy that uses fiat money, such as most economies today, the government controls the supply of money: legal restrictions give the government a monopoly on the printing of money. Just as the level of taxation and the level of government purchases are policy instruments of the government, so is the quantity of money. The government’s control over the money supply is called monetary policy.

In the United States and many other countries, monetary policy is delegated to a partially independent institution called the central bank. The central bank of the United States is the Federal Reserve—often called the Fed. If you look at a U.S. dollar bill, you will see that it is called a Federal Reserve Note. Decisions about monetary policy are made by the Fed’s Federal Open Market Committee. This committee consists of two groups: (1) members of the Federal Reserve Board, who are appointed by the president and confirmed by Congress, and (2) the presidents of the regional Federal Reserve Banks, who are chosen by these banks’ boards of directors. The Federal Open Market Committee meets about every six weeks to discuss and set monetary policy.

The primary way in which the Fed controls the supply of money is through open-

How the Quantity of Money Is Measured

One of our goals is to determine how the money supply affects the economy; we turn to that topic in the next chapter. As a background for that analysis, let’s first discuss how economists measure the quantity of money.

Because money is the stock of assets used for transactions, the quantity of money is the quantity of those assets. In simple economies, this quantity is easy to measure. In the POW camp, the quantity of money was the number of cigarettes in the camp. On the island of Yap, the quantity of money was the number of fei on the island. But how can we measure the quantity of money in more complex economies? The answer is not obvious, because no single asset is used for all transactions. People can use various assets, such as cash in their wallets or deposits in their checking accounts, to make transactions, although some assets are more convenient to use than others.

87

The most obvious asset to include in the quantity of money is currency, the sum of outstanding paper money and coins. Most day–

A second type of asset used for transactions is demand deposits, the funds people hold in their checking accounts. If most sellers accept personal checks or debit cards that access checking accounts balances, then assets in a checking account are almost as convenient as currency. That is, the assets are in a form that can easily facilitate a transaction. Demand deposits are therefore added to currency when measuring the quantity of money.

Once we admit the logic of including demand deposits in the measured money stock, many other assets become candidates for inclusion. Funds in savings accounts, for example, can be easily transferred into checking accounts or accessed by debit cards; these assets are almost as convenient for transactions. Money market mutual funds allow investors to write checks against their accounts, although restrictions sometimes apply with regard to the size of the check or the number of checks written. Because these assets can be easily used for transactions, they should arguably be included in the quantity of money.

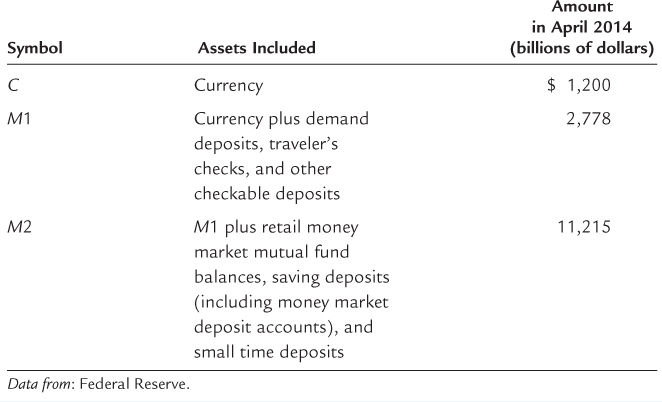

Because it is hard to judge which assets should be included in the money stock, more than one measure is available. Table 4-1 presents the three measures of the money stock that the Federal Reserve calculates for the U.S. economy, together with a list of which assets are included in each measure. From the smallest to the largest, they are designated C, M1, and M2. The most common measures for studying the effects of money on the economy are M1 and M2.

88

FYI

How Do Credit Cards and Debit Cards Fit into the Monetary System?

Many people use credit or debit cards to make purchases. Because money is the medium of exchange, one might naturally wonder how these cards fit into the measurement and analysis of money.

Let’s start with credit cards. One might guess that credit cards are part of the economy’s stock of money, but in fact measures of the quantity of money do not take credit cards into account. This is because credit cards are not really a method of payment but a method of deferring payment. When you buy an item with a credit card, the bank that issued the card pays the store what it is due. Later, you repay the bank. When the time comes to pay your credit card bill, you will likely do so by writing a check against your checking account. The balance in this checking account is part of the economy’s stock of money.

The story is different with debit cards, which automatically withdraw funds from a bank account to pay for items bought. Rather than allowing users to postpone payment for their purchases, a debit card allows users immediate access to deposits in their bank accounts. Using a debit card is similar to writing a check. The account balances that lie behind debit cards are included in measures of the quantity of money.

Even though credit cards are not a form of money, they are still important for analyzing the monetary system. Because people with credit cards can pay many of their bills all at once at the end of the month, rather than sporadically as they make purchases, they may hold less money on average than people without credit cards. Thus, the increased popularity of credit cards may reduce the amount of money that people choose to hold. In other words, credit cards are not part of the supply of money, but they may affect the demand for money.