4.3 How Central Banks Influence the Money Supply

Now that we have seen what money is and how the banking system affects the amount of money in the economy, we are ready to examine how the central bank influences the banking system and the money supply. This influence is the essence of monetary policy.

A Model of the Money Supply

If the Federal Reserve adds a dollar to the economy and that dollar is held as currency, the money supply increases by exactly one dollar. But as we have seen, if that dollar is deposited in a bank, and banks hold only a fraction of their deposits in reserve, the money supply increases by more than one dollar. As a result, to understand what determines the money supply under fractional–

The model has three exogenous variables:

The monetary base B is the total number of dollars held by the public as currency C and by the banks as reserves R. It is directly controlled by the Federal Reserve.

94

The reserve—

deposit ratio rr is the fraction of deposits that banks hold in reserve. It is determined by the business policies of banks and the laws regulating banks. The currency—

deposit ratio cr is the amount of currency C people hold as a fraction of their holdings of demand deposits D. It reflects the preferences of households about the form of money they wish to hold.

By showing how the money supply depends on the monetary base, the reserve–

We begin with the definitions of the money supply and the monetary base:

The first equation states that the money supply is the sum of currency and demand deposits. The second equation states that the monetary base is the sum of currency and bank reserves. To solve for the money supply as a function of the three exogenous variables (B, rr, and cr), we divide the first equation by the second to obtain

We then divide both the top and bottom of the expression on the right by D.

Note that C/D is the currency–

This equation shows how the money supply depends on the three exogenous variables.

We can now see that the money supply is proportional to the monetary base. The factor of proportionality, (cr + 1)/(cr + rr), is denoted m and is called the money multiplier. We can write

M = m × B.

Each dollar of the monetary base produces m dollars of money. Because the monetary base has a multiplied effect on the money supply, the monetary base is sometimes called high–

95

Here’s a numerical example. Suppose that the monetary base B is $800 billion, the reserve–

and the money supply is

M = 2.0 × $800 billion = $1,600 billion.

Each dollar of the monetary base generates two dollars of money, so the total money supply is $1,600 billion.

We can now see how changes in the three exogenous variables—

The money supply is proportional to the monetary base. Thus, an increase in the monetary base increases the money supply by the same percentage.

The lower the reserve–

deposit ratio, the more loans banks make, and the more money banks create from every dollar of reserves. Thus, a decrease in the reserve– deposit ratio raises the money multiplier and the money supply. The lower the currency–

deposit ratio, the fewer dollars of the monetary base the public holds as currency, the more base dollars banks hold as reserves, and the more money banks can create. Thus, a decrease in the currency– deposit ratio raises the money multiplier and the money supply.

With this model in mind, we can discuss the ways in which the Fed influences the money supply.

The Instruments of Monetary Policy

Although it is often convenient to make the simplifying assumption that the Federal Reserve controls the money supply directly, in fact the Fed controls the money supply indirectly using a variety of instruments. These instruments can be classified into two broad groups: those that influence the monetary base and those that influence the reserve–

How the Fed Changes the Monetary Base As we discussed earlier in the chapter, open–

96

The Fed can also alter the monetary base and the money supply by lending reserves to banks. Banks borrow from the Fed when they think they do not have enough reserves on hand, either to satisfy bank regulators, meet depositor withdrawals, make new loans, or satisfy some other business requirement. When the Fed lends to a bank that is having trouble obtaining funds from elsewhere, it is said to act as the lender of last resort.

There are various ways in which banks can borrow from the Fed. Traditionally, banks have borrowed at the Fed’s so-

In response to the financial crisis of 2008–

How the Fed Changes the Reserve–

Reserve requirements are Fed regulations that impose a minimum reserve–

In October 2008, the Fed started paying interest on reserves. That is, when a bank holds reserves on deposit at the Fed, the Fed now pays the bank interest on those deposits. This change gives the Fed another tool with which to influence the economy. The higher the interest rate on reserves, the more reserves banks will choose to hold. Thus, an increase in the interest rate on reserves will tend to increase the reserve–

97

CASE STUDY

Quantitative Easing and the Exploding Monetary Base

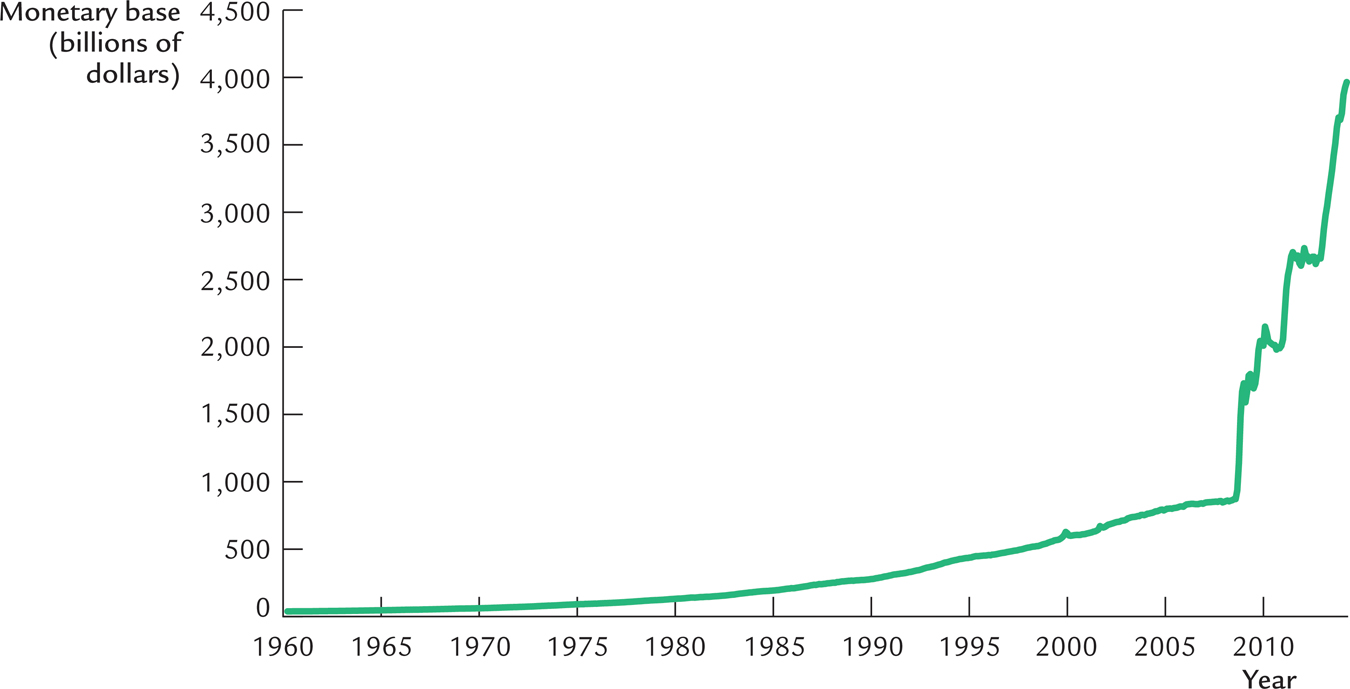

Figure 4-1 shows the monetary base from 1960 to 2014. You can see that something extraordinary happened in the last few years of this period. From 1960 to 2007, the monetary base grew gradually over time. But then from 2007 to 2014 it spiked up substantially, increasing about fivefold over just a few years.

This huge increase in the monetary base is attributable to actions the Federal Reserve took during the financial crisis and economic downturn of this period. With the financial markets in turmoil, the Fed pursued its job as a lender of last resort with historic vigor. It began by buying large quantities of mortgage-

98

The huge expansion in the monetary base, however, did not lead to a similar increase in broader measures of the money supply. While the monetary base increased about 400 percent from 2007 to 2014, M1 increased by only 100 percent and M2 by only 55 percent. These figures show that the tremendous expansion in the monetary base was accompanied by a large decline in the money multiplier. Why did this decline occur?

The model of the money supply presented earlier in this chapter shows that a key determinant of the money multiplier is the reserve ratio rr. From 2007 to 2014, the reserve ratio increased substantially because banks chose to hold substantial quantities of excess reserves. That is, rather than making loans, the banks kept much of their available funds in reserve. (Excess reserves rose from about $1.5 billion in 2007 to about $2.5 trillion in 2014.) This decision prevented the normal process of money creation that occurs in a system of fractional-

Why did banks choose to hold so much in excess reserves? Part of the reason is that banks had made many bad loans leading up to the financial crisis; when this fact became apparent, bankers tried to tighten their credit standards and make loans only to those they were confident could repay. In addition, interest rates had fallen to such low levels that making loans was not as profitable as it normally is. Banks did not lose much by leaving their financial resources idle as excess reserves.

Although the explosion in the monetary base did not lead to a similar explosion in the money supply, some observers feared that it still might. As the economy recovered from the economic downturn and interest rates rose to normal levels, they argued, banks could reduce their holdings of excess reserves by making loans. The money supply would start growing, perhaps too quickly.

Policymakers at the Federal Reserve, however, thought they could handle this problem if and when it arose. One possibility would be to drain the banking system of reserves by engaging in the opposite open-

Problems in Monetary Control

The various instruments give the Fed substantial power to influence the money supply. Nonetheless, the Fed cannot control the money supply perfectly. Bank discretion in conducting business can cause the money supply to change in ways the Fed did not anticipate. For example, banks may choose to hold more excess reserves, a decision that increases the reserve–

99

CASE STUDY

Bank Failures and the Money Supply in the 1930s

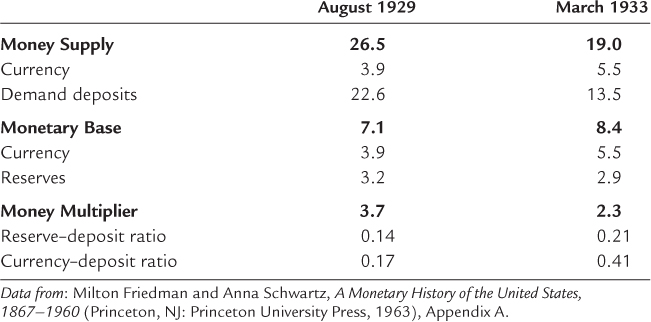

Between August 1929 and March 1933, the money supply fell 28 percent. As we will discuss in Chapter 12, some economists believe that this large decline in the money supply was the primary cause of the Great Depression of the 1930s, when unemployment reached unprecedented levels, prices fell precipitously, and economic hardship was widepread. In light of this hypothesis, one is naturally drawn to ask why the money supply fell so dramatically.

The three variables that determine the money supply—

Most economists attribute the fall in the money multiplier to the large number of bank failures in the early 1930s. From 1930 to 1933, more than 9,000 banks suspended operations, often defaulting on their depositors. The bank failures caused the money supply to fall by altering the behavior of both depositors and bankers.

Bank failures raised the currency–

100

In addition, the bank failures raised the reserve–

Although it is easy to explain why the money supply fell, it is more difficult to decide whether to blame the Federal Reserve. One might argue that the monetary base did not fall, so the Fed should not be blamed. Critics of Fed policy during this period make two counterarguments. First, they claim that the Fed should have taken a more vigorous role in preventing bank failures by acting as a lender of last resort when banks needed cash during bank runs. This would have helped maintain confidence in the banking system and prevented the large fall in the money multiplier. Second, they point out that the Fed could have responded to the fall in the money multiplier by increasing the monetary base even more than it did. Either of these actions would likely have prevented such a large fall in the money supply, which in turn might have reduced the severity of the Great Depression.

Since the 1930s, many policies have been put into place that make such a large and sudden fall in the money supply less likely today. Most important, the system of federal deposit insurance protects depositors when a bank fails. This policy is designed to maintain public confidence in the banking system and thus prevents large swings in the currency–