Unemployment and the Labor Market

A man willing to work, and unable to find work, is perhaps the saddest sight that fortune’s inequality exhibits under the sun.

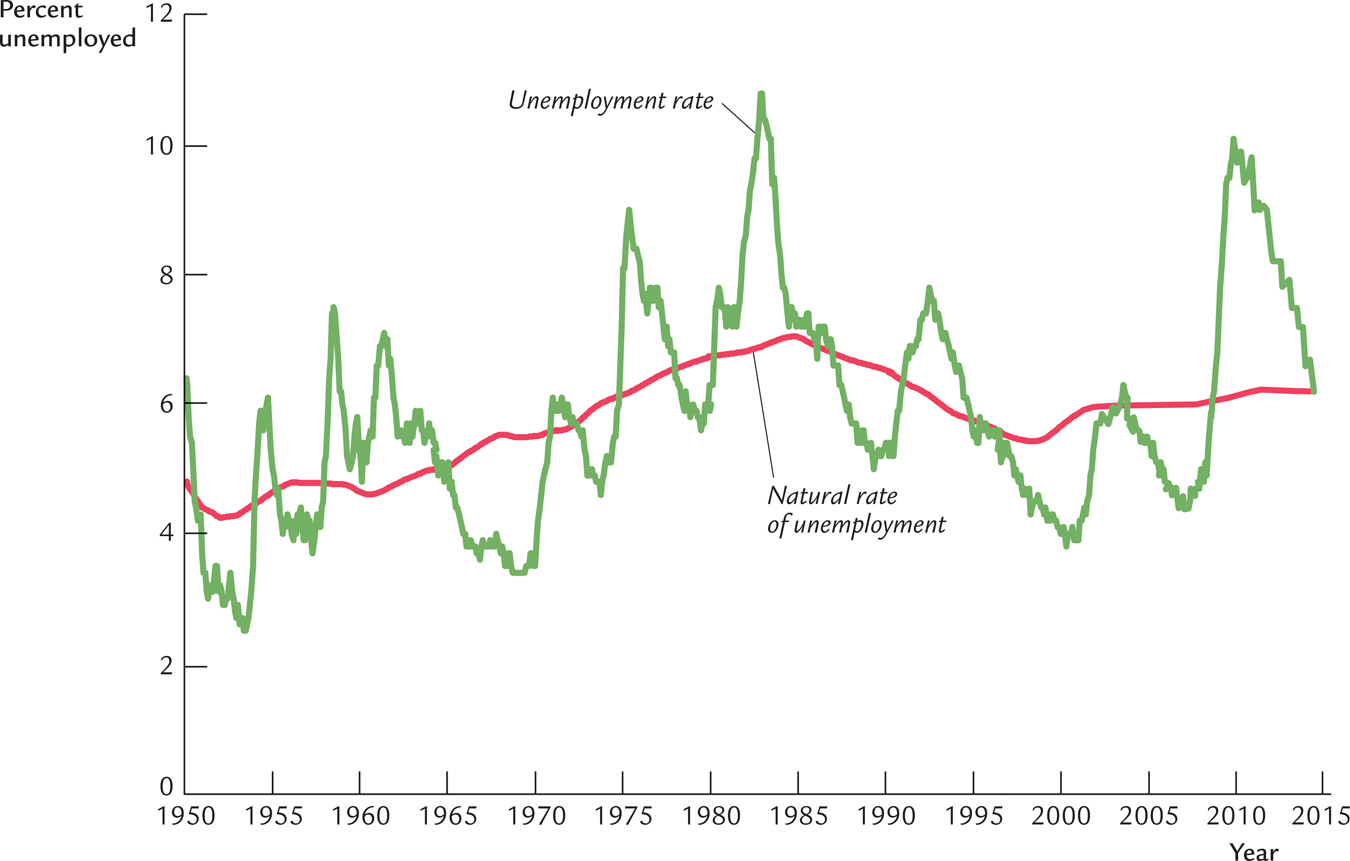

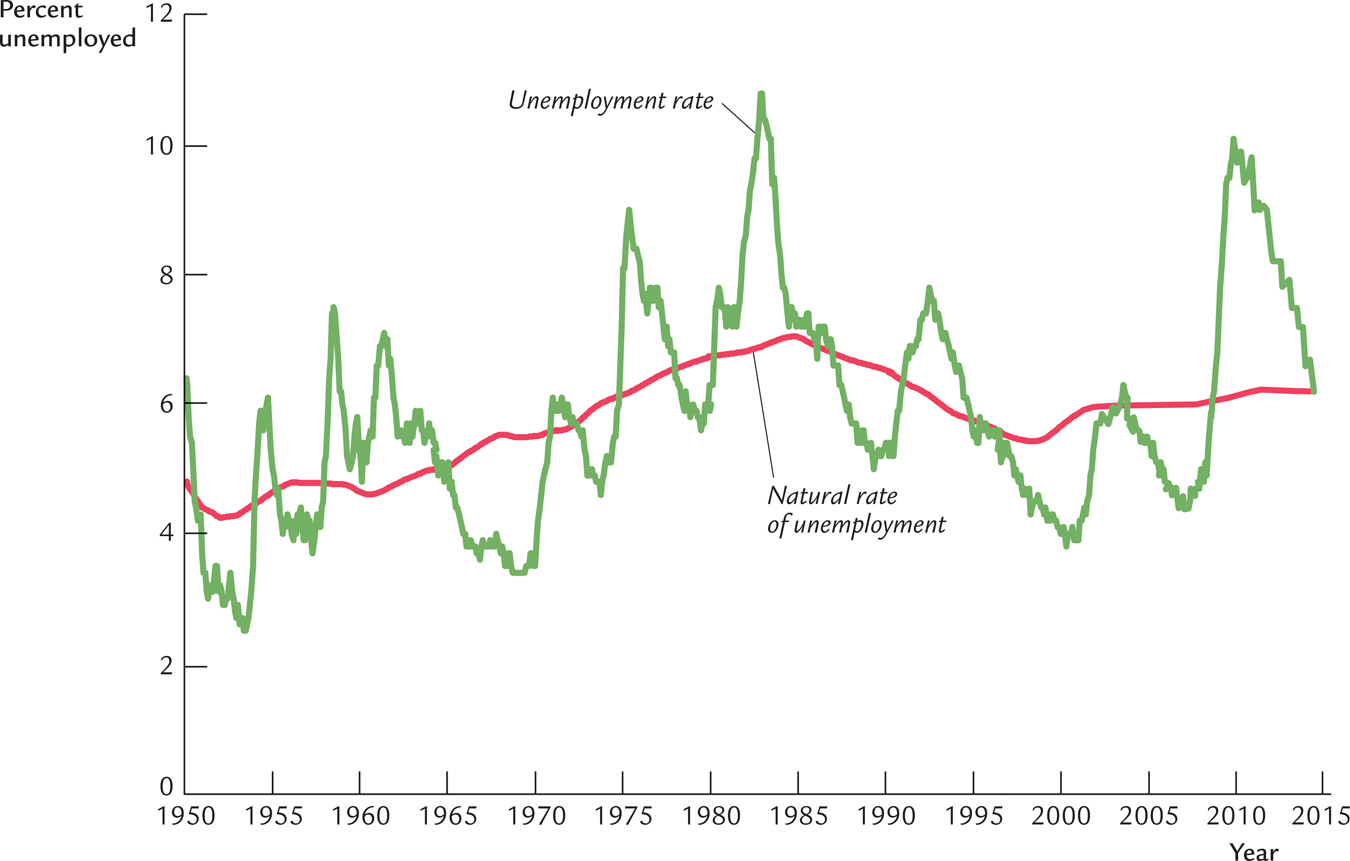

Unemployment is the macroeconomic problem that affects people most directly and severely. For most people, the loss of a job means a reduced living standard and psychological distress. It is no surprise that unemployment is a frequent topic of political debate and that politicians often claim that their proposed policies would help create jobs. While the issue is perennial, it rose to particular prominence in the aftermath of the financial crisis and recession of 2008–2009, when the unemployment rate lingered around 9 percent for several years before drifting down to about 6 percent in 2014.

Economists study unemployment to identify its causes and to help improve the public policies that affect the unemployed. Some of these policies, such as job-training programs, help people find employment. Others, such as unemployment insurance, alleviate some of the hardships that the unemployed face. Still other policies affect the prevalence of unemployment inadvertently. Laws mandating a high minimum wage, for instance, are widely thought to raise unemployment among the least skilled and least experienced members of the labor force.

Our discussions of the labor market so far have ignored unemployment. In particular, the model of national income in Chapter 3 was built with the assumption that the economy is always at full employment. In reality, not everyone in the labor force has a job all the time: in all free-market economies, at any moment, some people are unemployed.

Figure 7-1 shows the rate of unemployment—the percentage of the labor force unemployed—in the United States from 1950 to 2014. Although the rate of unemployment fluctuates from year to year, it never gets even close to zero. The average is between 5 and 6 percent, meaning that about 1 out of every 18 people wanting a job does not have one.

Figure 7.1: FIGURE 7-1: The Unemployment Rate and the Natural Rate of Unemployment in the United States There is always some unemployment. The natural rate of unemployment is the average level around which the unemployment rate fluctuates. (The natural rate of unemployment for any particular month is estimated here by averaging all the unemployment rates from ten years earlier to ten years later. Future unemployment rates are set at 5.5 percent.)

Data from: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In this chapter we begin our study of unemployment by discussing why there is always some unemployment and what determines its level. We do not study what determines the year-to-year fluctuations in the rate of unemployment until Part Four of this book, which examines short-run economic fluctuations. Here we examine the determinants of the natural rate of unemployment—the average rate of unemployment around which the economy fluctuates. The natural rate is the rate of unemployment toward which the economy gravitates in the long run, given all the labor-market imperfections that impede workers from instantly finding jobs.