PROBLEMS AND APPLICATIONS

For any problem marked with  , there is a Work It Out online tutorial available for a similar problem. To access these interactive, step-

, there is a Work It Out online tutorial available for a similar problem. To access these interactive, step-

Question 7.6

1. Answer the following questions about your own experience in the labor force.

When you or one of your friends is looking for a part-

time job, how many weeks does it typically take? After you find a job, how many weeks does it typically last? From your estimates, calculate (in a rate per week) your rate of job finding f and your rate of job separation s. (Hint: If f is the rate of job finding, then the average spell of unemployment is 1/f.)

What is the natural rate of unemployment for the population you represent?

Question 7.7

2.  • The residents of a certain dormitory have collected the following data: people who live in the dorm can be classified as either involved in a relationship or uninvolved. Among involved people, 10 percent experience a breakup of their relationship every month. Among uninvolved people, 5 percent enter into a relationship every month. What is the steady-

• The residents of a certain dormitory have collected the following data: people who live in the dorm can be classified as either involved in a relationship or uninvolved. Among involved people, 10 percent experience a breakup of their relationship every month. Among uninvolved people, 5 percent enter into a relationship every month. What is the steady-

Question 7.8

3. In this chapter we saw that the steady-

Question 7.9

4. Suppose that Congress passes legislation making it more difficult for firms to fire workers. (An example is a law requiring severance pay for fired workers.) If this legislation reduces the rate of job separation without affecting the rate of job finding, how would the natural rate of unemployment change? Do you think it is plausible that the legislation would not affect the rate of job finding? Why or why not?

Question 7.10

5.  • Consider an economy with the following Cobb–

• Consider an economy with the following Cobb–

Y = 5K1/3L2/3.

Derive the equation describing labor demand in this economy as a function of the real wage and the capital stock. (Hint: Review Chapter 3.)

The economy has 27,000 units of capital and a labor force of 1,000 workers. Assuming that factor prices adjust to equilibrate supply and demand, calculate the real wage, total output, and the total amount earned by workers.

Now suppose that Congress, concerned about the welfare of the working class, passes a law setting a minimum wage that is 10 percent above the equilibrium wage you derived in part (b). Assuming that Congress cannot dictate how many workers are hired at the mandated wage, what are the effects of this law? Specifically, calculate what happens to the real wage, employment, output, and the total amount earned by workers.

210

Does Congress succeed in its goal of helping the working class? Explain.

Do you think that this analysis provides a good way of thinking about a minimum-

wage law? Why or why not?

Question 7.11

6. Suppose that a country experiences a reduction in productivity—

What happens to the labor demand curve?

How would this change in productivity affect the labor market—

that is, employment, unemployment, and real wages— if the labor market is always in equilibrium? How would this change in productivity affect the labor market if unions prevent real wages from falling?

Question 7.12

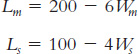

7.  • Consider an economy with two sectors: manufacturing and services. Demand for labor in manufacturing and services are described by these equations:

• Consider an economy with two sectors: manufacturing and services. Demand for labor in manufacturing and services are described by these equations:

where L is labor (in number of workers), W is the wage (in dollars), and the subscripts denote the sectors. The economy has 100 workers who are willing and able to work in either sector.

If workers are free to move between sectors, what relationship will there be between Wm and Ws?

Suppose that the condition in part (a) holds and wages adjust to equilibrate labor supply and labor demand. Calculate the wage and employment in each sector.

Suppose a union establishes itself in manufacturing and pushes the manufacturing wage to $25. Calculate employment in manufacturing.

In the aftermath of the unionization of manufacturing, all workers who cannot get the highly paid union jobs move to the service sector. Calculate the wage and employment in services.

Now suppose that workers have a reservation wage of $15—

that is, rather than taking a job at a wage below $15, they would rather wait for a $25 union job to open up. Calculate the wage and employment in each sector. What is the economy’s unemployment rate?

Question 7.13

8. When workers’ wages rise, their decision about how much time to spend working is affected in two conflicting ways—

Question 7.14

9. In any city at any time, some of the stock of usable office space is vacant. This vacant office space is unemployed capital. How would you explain this phenomenon? In particular, which approach to explaining unemployed labor applies best to unemployed capital? Do you think unemployed capital is a social problem? Explain your answer.

1 Robert E. Hall, “A Theory of the Natural Rate of Unemployment and the Duration of Unemployment,” Journal of Monetary Economics 5 (April 1979): 153–

2 Lawrence F. Katz and Bruce D. Meyer, “Unemployment Insurance, Recall Expectations, and Unemployment Outcomes,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 105 (November 1990): 973–

3 Stephen A. Woodbury and Robert G. Spiegelman, “Bonuses to Workers and Employers to Reduce Unemployment: Randomized Trials in Illinois,” American Economic Review 77 (September 1987): 513–

4 Charles Brown, “Minimum Wage Laws: Are They Overrated?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 2 (Summer 1988): 133–

5 The figures reported here are from the Web site of the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The link is http:/

6 For more extended discussions of efficiency wages, see Janet Yellen, “Efficiency Wage Models of Unemployment,” American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings (May 1984): 200–

7 Jeremy I. Bulow and Lawrence H. Summers, “A Theory of Dual Labor Markets with Application to Industrial Policy, Discrimination, and Keynesian Unemployment,” Journal of Labor Economics 4 (July 1986): 376–

8 From The New York Times, July 05, 2010, © 2010 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without express written permission is prohibited.

9 For more discussion of these issues, see Paul Krugman, “Past and Prospective Causes of High Unemployment,” in Reducing Unemployment: Current Issues and Policy Options, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, August 1994.

10 Stephen Nickell, “Unemployment and Labor Market Rigidities: Europe Versus North America,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 11 (September 1997): 55–

11 To read more about this topic, see Edward C. Prescott “Why Do Americans Work So Much More Than Europeans?” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review 28, no. 1 (July 2004): 2–