7.5 Labor-Market Experience: Europe

Although our discussion has focused largely on the United States, many fascinating and sometimes puzzling phenomena become apparent when economists compare the experiences of Americans in the labor market with those of Europeans.

The Rise in European Unemployment

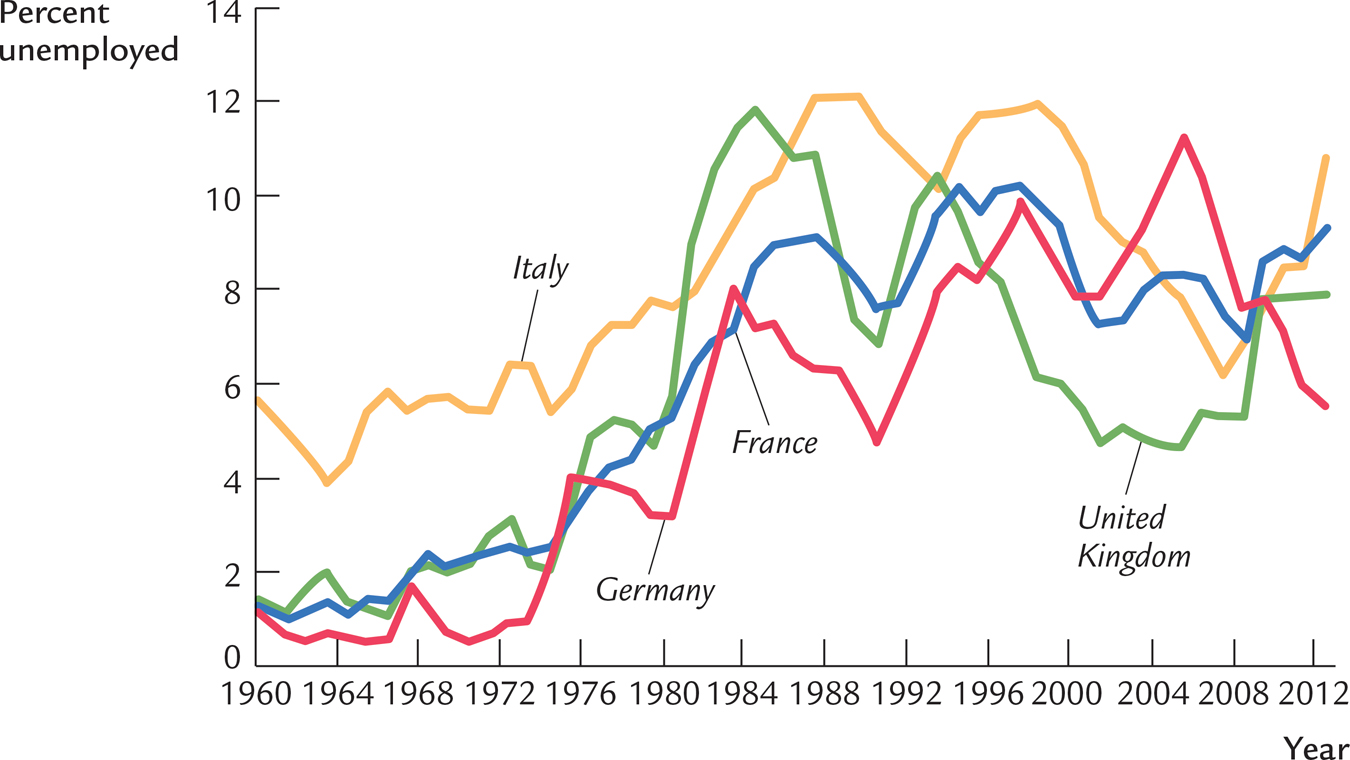

Figure 7-6 shows the rate of unemployment from 1960 to 2012 in the four largest European countries—

What is the cause of rising European unemployment? No one knows for sure, but there is a leading theory. Many economists believe that the problem can be traced to the interaction between a long-

204

There is no question that most European countries have generous programs for those without jobs. These programs go by various names: social insurance, the welfare state, or simply “the dole.” Many countries allow the unemployed to collect benefits for years, rather than for only a short period of time as in the United States. In some sense, those living on the dole are really out of the labor force: given the employment opportunities available, taking a job is less attractive than remaining without work. Yet these people are often counted as unemployed in government statistics.

There is also no question that the demand for unskilled workers has fallen relative to the demand for skilled workers. This change in demand is probably due to changes in technology: computers, for example, increase the demand for workers who can use them and reduce the demand for those who cannot. In the United States, this change in demand has been reflected in wages rather than unemployment: over the past three decades, the wages of unskilled workers have fallen substantially relative to the wages of skilled workers. In Europe, however, the welfare state provides unskilled workers with an alternative to working for low wages. As the wages of unskilled workers fall, more workers view the dole as their best available option. The result is higher unemployment.

This diagnosis of high European unemployment does not suggest an easy remedy. Reducing the magnitude of government benefits for the unemployed would encourage workers to get off the dole and accept low-

Unemployment Variation Within Europe

Europe is not a single labor market but is, instead, a collection of national labor markets, separated not only by national borders but also by differences in culture and language. Because these countries differ in their labor-

The first noteworthy fact is that the unemployment rate varies substantially from country to country. For example, in March 2014, when the unemployment rate was 6.7 percent in the United States, it was 5.1 percent in Germany and 25.3 percent in Spain. Although in recent years average unemployment has been higher in Europe than in the United States, many Europeans live in nations with unemployment rates lower than the U.S. rate.

A second notable fact is that much of the variation in unemployment rates is attributable to the long-

205

National unemployment rates are correlated with a variety of labor-

Although government spending on unemployment insurance seems to raise unemployment, spending on “active” labor-

The role of unions also varies from country to country, as we saw in Table 7-1. This fact also helps explain differences in labor-

A word of warning: correlation does not imply causation, so empirical results such as these should be interpreted with caution. But they do suggest that a nation’s unemployment rate, rather than being immutable, is instead a function of the choices a nation makes.10

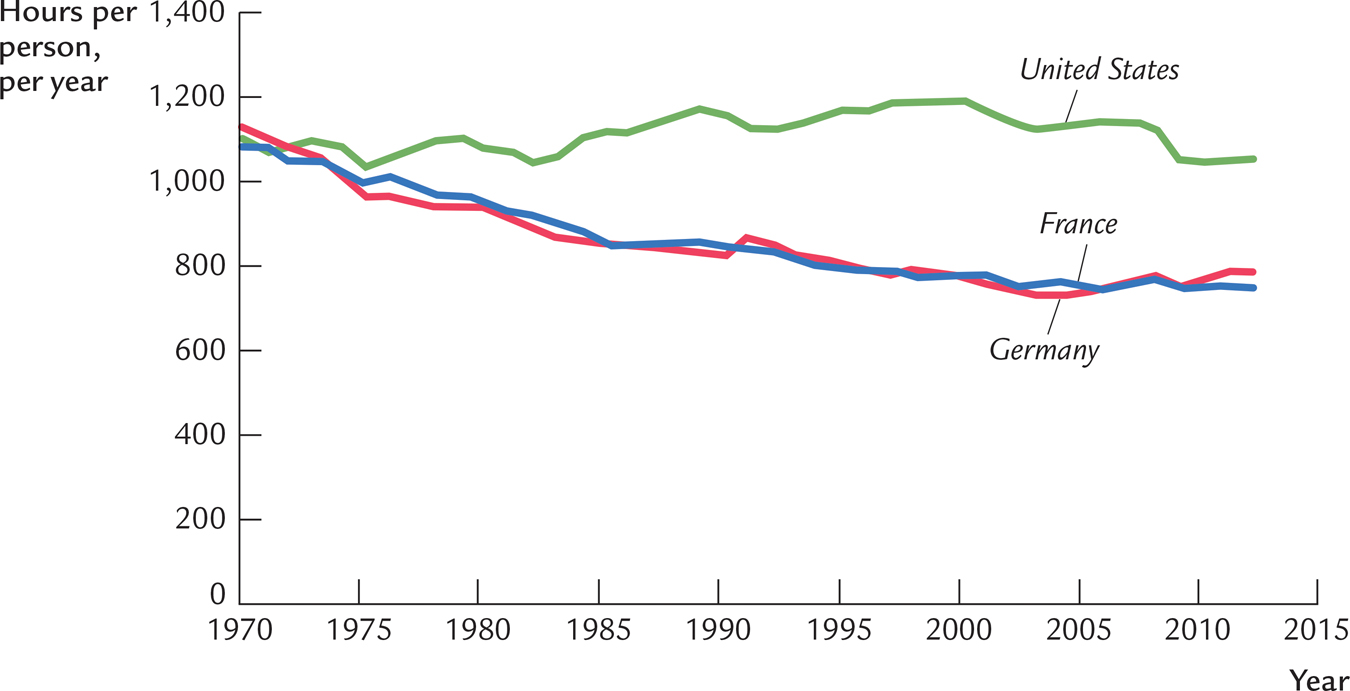

The Rise of European Leisure

Higher unemployment rates in Europe are part of the larger phenomenon that Europeans typically work fewer hours than do their American counterparts. Figure 7-7 presents some data on how many hours a typical person works in the United States, France, and Germany. In the early 1970s, the number of hours worked was about the same in each of these countries. But since then, the number of hours has stayed level in the United States, while it has declined substantially in Europe. Today, the typical American works many more hours than the typical resident of these two western European countries.

The difference in hours worked reflects two facts. First, the average employed person in the United States works more hours per year than the average employed person in Europe. Europeans typically enjoy shorter workweeks and more frequent holidays. Second, more potential workers are employed in the United States.

206

That is, the employment-

What is the underlying cause of these differences in work patterns? Economists have proposed several hypotheses.

Edward Prescott, the 2004 winner of the Nobel Prize in economics, has concluded that “virtually all of the large differences between U.S. labor supply and those of Germany and France are due to differences in tax systems.” This hypothesis is consistent with two facts: (1) Europeans face higher tax rates than Americans, and (2) European tax rates have risen significantly over the past several decades. Some economists take these facts as powerful evidence for the impact of taxes on work effort. Yet others are skeptical, arguing that to explain the difference in hours worked by tax rates alone requires an implausibly large elasticity of labor supply.

A related hypothesis is that the difference in observed work effort may be attributable to the underground economy. When tax rates are high, people have a greater incentive to work “off the books” to evade taxes. For obvious reasons, data on the underground economy are hard to come by. But economists who study the subject believe the underground economy is larger in Europe than it is in the United States. This fact suggests that the difference in actual hours worked, including work in the underground economy, may be smaller than the difference in measured hours worked.

207

Another hypothesis stresses the role of unions. As we have seen, collective bargaining is more important in European than in U.S. labor markets. Unions often push for shorter workweeks in contract negotiations, and they lobby the government for a variety of labor-

A final hypothesis emphasizes the possibility of different preferences. As technological advance and economic growth have made all advanced countries richer, people around the world must decide whether to take the greater prosperity in the form of increased consumption of goods and services or increased leisure. According to economist Olivier Blanchard, “the main difference [between the continents] is that Europe has used some of the increase in productivity to increase leisure rather than income, while the U.S. has done the opposite.” Blanchard believes that Europeans simply have more taste for leisure than do Americans. (As a French economist working in the United States, he may have special insight into this phenomenon.) If Blanchard is right, this raises the even harder question of why tastes vary by geography.

Economists continue to debate the merits of these alternative hypotheses. In the end, there may be some truth to all of them.11