4.5 The Nominal Interest Rate and the Demand for Money

The quantity theory is based on a simple money demand function: it assumes that the demand for real money balances is proportional to income. Although the quantity theory is a good place to start when analyzing the effects of money on the economy, it is not the whole story. Here we add another determinant of the quantity of money demanded—the nominal interest rate.

The Cost of Holding Money

106

The money you hold in your wallet does not earn interest. If instead of holding that money you used it to buy government bonds or deposited it in a savings account, you would earn the nominal interest rate. Therefore, the nominal interest rate is the opportunity cost of holding money: it is what you give up by holding money rather than bonds.

Another way to see that the cost of holding money equals the nominal interest rate is by comparing the real returns on alternative assets. Assets other than money, such as government bonds, earn the real return r. Money earns an expected real return of –Eπ, because its real value declines at the rate of inflation. When you hold money, you give up the difference between these two returns. Thus, the cost of holding money is r – (-Eπ), which the Fisher equation tells us is the nominal interest rate i.

Just as the quantity of bread demanded depends on the price of bread, the quantity of money demanded depends on the price of holding money. Hence, the demand for real money balances depends both on the level of income and on the nominal interest rate. We write the general money demand function as

(M/P)d = L(i, Y).

The letter L is used to denote money demand because money is the economy’s most liquid asset (the asset most easily used to make transactions). This equation states that the demand for the liquidity of real money balances is a function of income and the nominal interest rate. The higher the level of income Y, the greater the demand for real money balances. The higher the nominal interest rate i, the lower the demand for real money balances. This dependence of money demand on the interest rate is central to our discussion of short-run stabilization policy in Chapters 11 and 12.

Of course, money demand depends on other things as well—such as innovations in the financial sector (for example, the development of money substitutes). Our discussion abstracts from such other long-run trends.

Future Money and Current Prices

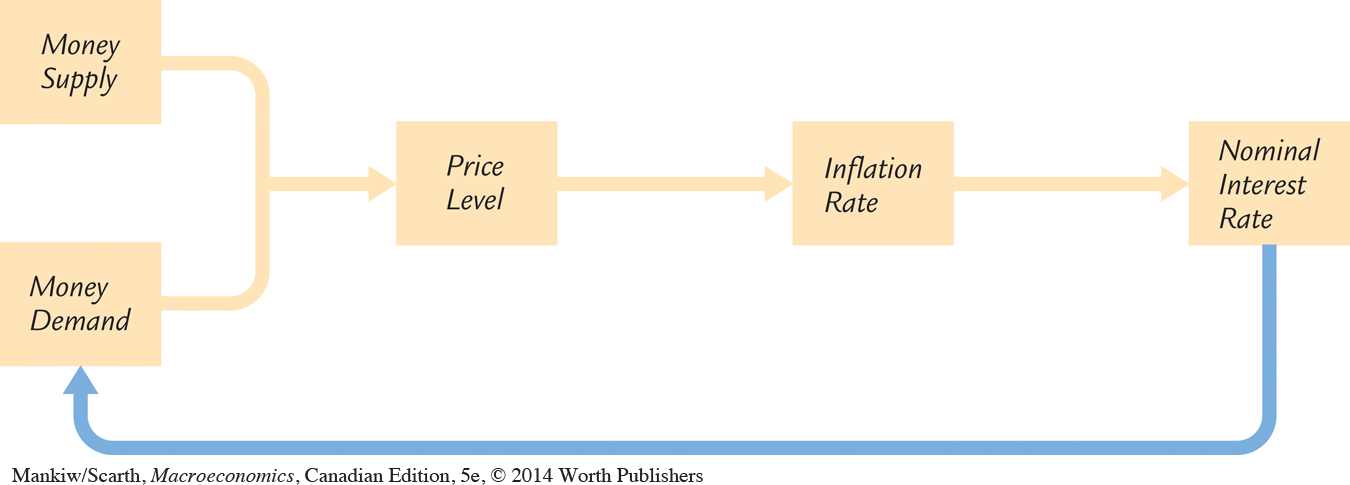

Money, prices, and interest rates are now related in several ways. Figure 4-5 illustrates the linkages we have discussed. As the quantity theory of money explains, money supply and money demand together determine the equilibrium price level. Changes in the price level are, by definition, the rate of inflation. Inflation, in turn, affects the nominal interest rate through the Fisher effect. But now, because the nominal interest rate is the cost of holding money, the nominal interest rate feeds back to affect the demand for money.

Consider how introduction of this last link affects our theory of the price level. First, equate the supply of real money balances M/P to the demand L(i, Y):

M/P = L(i, Y).

107

Next, use the Fisher equation to write the nominal interest rate as the sum of the real interest rate and expected inflation:

M/P = L(r + Eπ, Y).

This equation states that the level of real money balances depends on the expected rate of inflation.

The last equation tells a more sophisticated story about the determination of the price level than does the quantity theory. The quantity theory of money says that today’s money supply determines today’s price level. This conclusion remains partly true: if the nominal interest rate and the level of output are held constant, the price level moves proportionately with the money supply. Yet the nominal interest rate is not constant; it depends on expected inflation, which in turn depends on growth in the money supply. The presence of the nominal interest rate in the money demand function yields an additional channel through which money supply affects the price level.

This general money demand equation implies that the price level depends not just on today’s money supply but also on the money supply expected in the future. To see why, suppose the Bank of Canada announces that it will increase the money supply in the future, but it does not change the money supply today. This announcement causes people to expect higher money growth and higher inflation. Through the Fisher effect, this increase in expected inflation raises the nominal interest rate. The higher nominal interest rate immediately increases the cost of holding money and therefore reduces the demand for real money balances. Because the central bank has not changed the quantity of money available today, the reduced demand for real money balances leads to a higher price level. Hence, higher expected money growth in the future leads to a higher price level today.

108

The effect of money on prices is fairly complex. The appendix to this chapter presents the Cagan model, which shows how the price level is related to current and expected future money. The conclusion of the analysis is that the price level depends on a weighted average of the current money supply and the money supply expected to prevail in the future.

CASE STUDY

Canadian Monetary Policy

Given the fact that the price level depends on the money supply that is expected to prevail in the future, it is not surprising that Stephen Poloz, the current Governor of the Bank of Canada, consistently stresses his commitment to maintaining low inflation. Indeed, well before Mr. Poloz was appointed, the government had opted for a series of five-year inflation targets—a commitment that the Bank of Canada would keep inflation within the range of 1–3 percent for five years. The point of making this announcement and drawing so much attention to it was to try to convince individuals and firms that the Bank of Canada really would keep money growth limited for the foreseeable future. Clearly, the officials in both the Department of Finance and the Bank of Canada believe that inflation now depends very much on the rate at which private agents expect the Bank will issue money in the future. Policy is based on the view that the Bank of Canada’s “credibility” must be maintained, and that this stance involves convincing private individuals that money growth will not be excessive.

In the debates on constitutional change in 1992, one of the federal government’s proposals was that the Bank of Canada Act be changed to make the maintenance of price stability the sole objective of monetary policy. The government wanted to dispell any notions people might have that the Bank would give up its commitment to price stability, even if some other crisis, such as a deep recession, emerged. Clearly, officials believe that the analysis we have just summarized is directly relevant to the Canadian policy challenge.