The Invention of Writing and the First Schools

The origins of writing probably go back to the ninth millennium B.C.E., when Near Eastern peoples used clay tokens as counters for record keeping. By the fourth millennium, people had realized that impressing the tokens on clay, or drawing pictures of the tokens on clay, was simpler than making tokens. This breakthrough in turn suggested that more information could be conveyed by adding pictures of still other objects. The result was a complex system of pictographs in which each sign pictured an object. These pictographs were the forerunners of the Sumerian form of writing known as cuneiform (kyou-

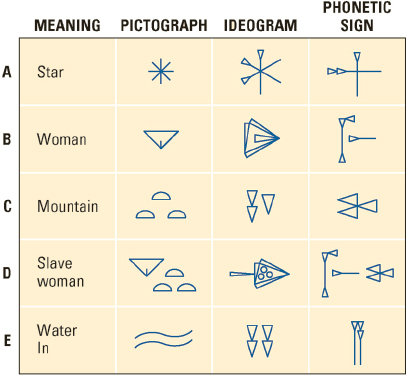

Pictographs were initially limited in that they could not represent abstract ideas, but the development of ideograms — signs that represented ideas — made writing more versatile. Thus the sign for star could also be used to indicate heaven, sky, or even god. The real breakthrough came when scribes started using signs to represent sounds.

Sumerian Writing

Sumerian Writing(Source: S. N. Kramer, The Sumerians: Their History, Culture and Character. Copyright © 1963 by The University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved. Used by permission of the publisher.)

Over time, the Sumerian system of writing became so complicated that scribal schools were established; by 2500 B.C.E.,these schools flourished throughout Sumer. Students at the schools were all male, and most came from families in the middle range of urban society. Scribal schools were primarily intended to produce individuals who could keep records of the property of temple officials, kings, and nobles. Thus writing first developed as a way to enhance the growing power of elites, not to record speech, although it later came to be used for that purpose.