The Rise of Phoenicia

While Kush expanded in the southern Nile Valley, another group rose to prominence along the Mediterranean coast of modern Lebanon, the northern part of the area called Canaan in ancient sources. These Canaanites established the prosperous commercial centers of Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos, and were master shipbuilders. Between about 1100 and 700 B.C.E., the residents of these cities became the seaborne merchants of the Mediterranean. Their most valued products were purple and blue textiles, from which originated their Greek name, Phoenicians (fih-

The trading success of the Phoenicians brought them prosperity. In addition to textiles and purple dye, they began to manufacture goods for export, such as tools, weapons, and cookware. Phoenician ships often carried hundreds of jars of wine, and the Phoenicians introduced grape growing to new regions around the Mediterranean, dramatically increasing the wine available for consumption and trade. They imported rare goods and materials from Persia in the east and their neighbors to the south. They also expanded their trade to Egypt, where they mingled with other local traders.

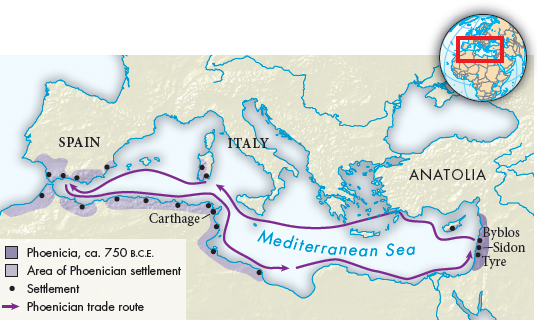

Moving beyond Egypt, the Phoenicians struck out along the coast of North Africa to establish new markets in places where they encountered little competition. In the ninth century B.C.E., they founded, in modern Tunisia, the city of Carthage, which prospered to become the leading city in the western Mediterranean.

The Phoenicians planted trading posts and small farming communities along the coast, founding colonies in Spain and Sicily along with Carthage. Their trade routes eventually took them to the far western Mediterranean and beyond to the Atlantic coast of modern-

The Phoenicians’ overwhelming cultural achievement was the spread of a completely phonetic system of writing — that is, an alphabet. Writers of both cuneiform and hieroglyphics had developed signs that were used to represent sounds, but these were always used with a much larger number of ideograms. Sometime around 1800 B.C.E., workers in the Sinai Peninsula, which was under Egyptian control, began to write only with phonetic signs, with each sign designating one sound. This system vastly simplified writing and reading, and spread among common people as a practical way to record ideas and communicate. The Phoenicians adopted the simpler system for their own language and spread it around the Mediterranean. The system invented by ordinary people and spread by Phoenician merchants is the origin of most of the world’s phonetic alphabets today.

>QUICK REVIEW

How did the Kushites and the Phoenicians take advantage of regional trade opportunities in the aftermath of the collapse of the Bronze Age empires?