Military Campaigns

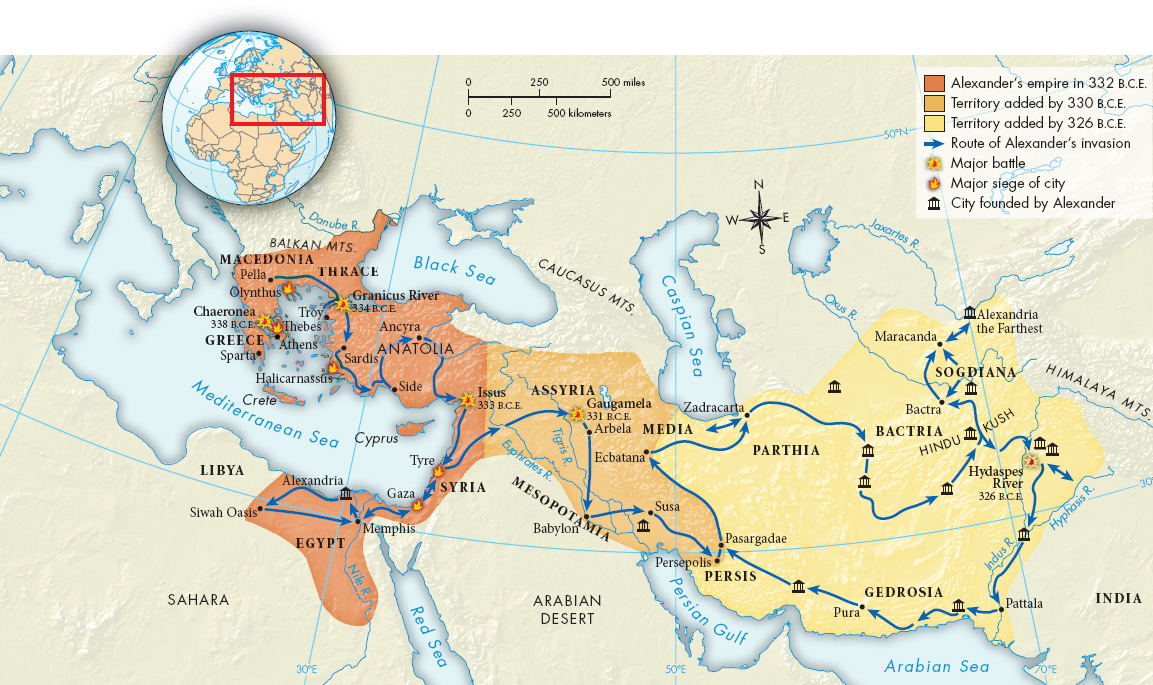

In 334 B.C.E., Alexander led an army of Macedonians and Greeks into Persian territory in Asia Minor. In the next three years, Alexander moved east into the Persian Empire, winning major battles at the Granicus River and Issus (Map 4.1). He moved into Syria and took most of the cities of Phoenicia and the eastern coast of the Mediterranean. He then turned south toward Egypt, which had earlier been conquered by the Persians. The Egyptians saw Alexander as a liberator, and he seized Egypt without a battle. After honoring the priestly class, Alexander was proclaimed pharaoh, the legitimate ruler of the country. He founded a new capital, Alexandria, on the coast of the Mediterranean, which would later grow into an enormous city.

Alexander left Egypt after less than a year and marched into Assyria, where at Gaugamela he defeated the Persian army. After this victory, the principal Persian capital of Persepolis fell to him in a bitterly fought battle. There he performed a symbolic act of retribution by burning the royal buildings of King Xerxes, the invader of Greece during the Persian wars 150 years earlier. In 330 B.C.E., he took Ecbatana, the last Persian capital, and pursued the Persian king Darius III to his death.

The Persian Empire had fallen, but Alexander had no intention of stopping. Many of his troops had been supplied by Greek city-

ONLINE DOCUMENT PROJECT

Alexander the Great

What were the motives behind Alexander’s conquests, and what were the consequences of Hellenization?

Keeping the question above in mind, explore a variety of ancient perspectives on these questions.

See Document Project for Chapter 4.

In 326 B.C.E., Alexander crossed the Indus River and entered India (in the area that is now Pakistan). There, too, he saw hard fighting, and finally at the Hyphasis (HIH-

Alexander’s legendary status makes a reasoned interpretation of his goals and character very difficult. His contemporaries from the Greek city-