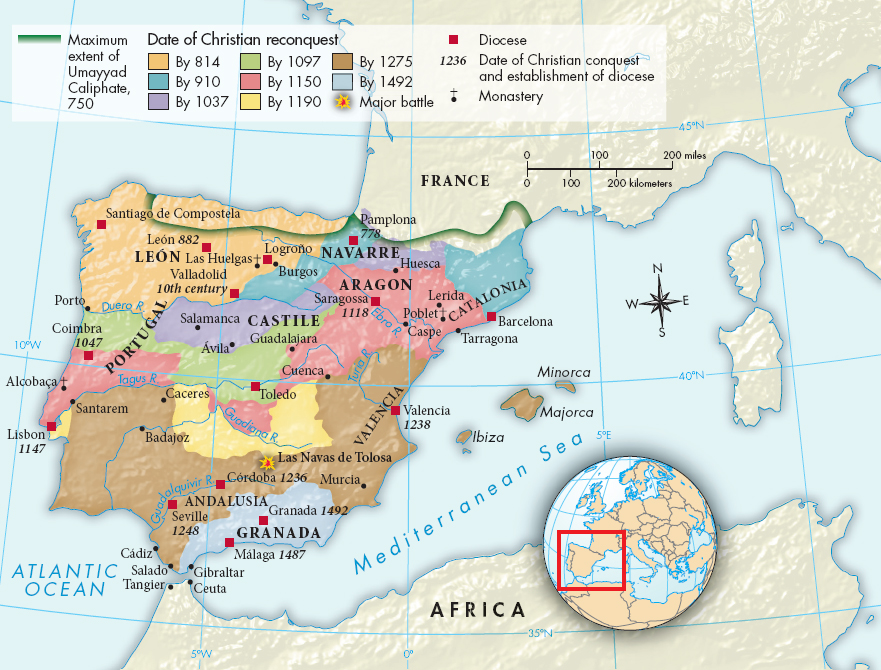

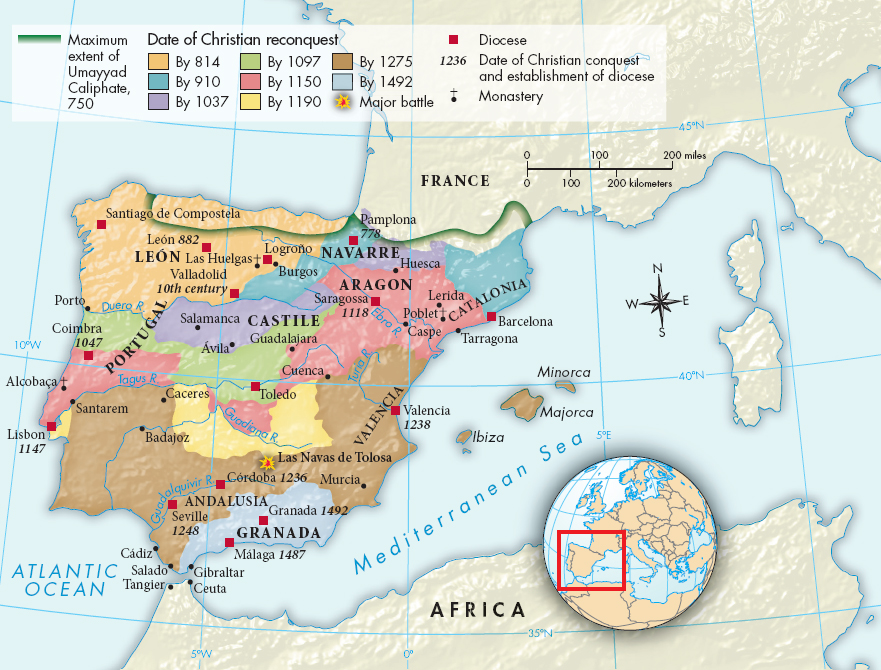

From the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries, power in the Iberian Peninsula shifted from Muslim to Christian rulers, with the tide turning decisively in favor of the Christian forces beginning in the early thirteenth century. Alfonso VIII (1158–1214) of Castile, aided by the kings of Aragon, Navarre, and Portugal, won a crushing victory over the Muslims in 1212, accelerating the Christian push southward. Over the next several centuries, successive popes gave Christian warriors in the Iberian Peninsula the same spiritual benefits that they gave those who traveled to Jerusalem, such as granting them forgiveness for their sins. By doing so, the popes transformed this advance into a crusade. Christian troops captured the great Muslim cities of Córdoba in 1236 and Seville in 1248. With this, Christians controlled nearly the entire Iberian Peninsula, save for the small state of Granada (Map 9.3). The chief mosques in Muslim cities became cathedrals, and Christian rulers recruited immigrants from western and southern Europe. The cities quickly became overwhelmingly Christian, and gradually rural areas did as well. Fourteenth-century clerical writers would call the movement to expel the Muslims the reconquista (reconquest), a sacred and patriotic crusade to wrest the country from “alien” Muslim hands.

MAP 9.3

The Reconquista, ca. 750–1492 The Christian conquest of Muslim Spain was followed by ecclesiastical reorganization, with the establishment of dioceses, monasteries, and the Latin liturgy, which gradually tied the peninsula to the heartland of Christian Europe and to the Roman papacy.