Individuals in Society: Leonardo da Vinci

What makes a genius? A deep curiosity about an extensive variety of subjects? A divine spark that emerges in talents that far exceed the norm? Or is it just “one percent inspiration and ninety-

Leonardo’s most famous portrait, Mona Lisa, shows a woman with an enigmatic smile that Giorgio Vasari described as “so pleasing that it seemed divine rather than human.” The portrait, probably of the young wife of a rich Florentine merchant (her exact identity is hotly debated), may be the best-

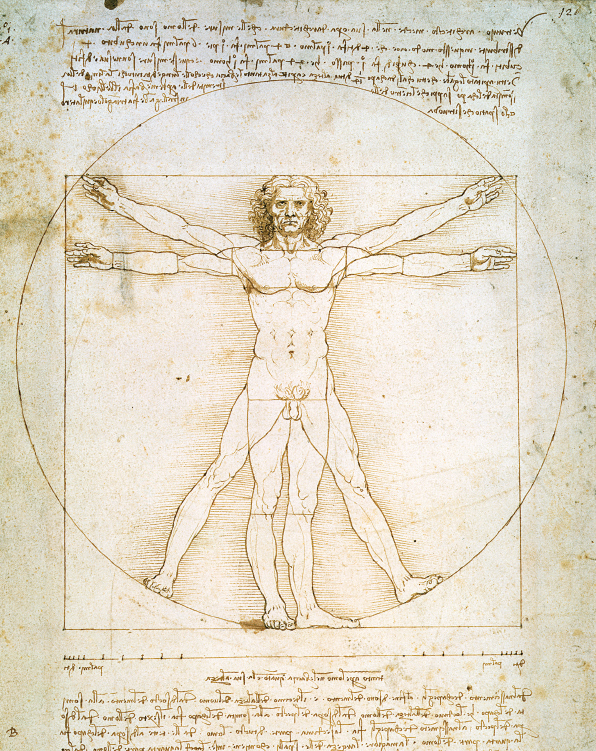

Leonardo’s reputation as a genius does not rest on his paintings, however, which are actually few in number, but rather on the breadth of his abilities and interests. He is considered by many the first “Renaissance man,” a phrase still used for a multitalented individual. Hoping to reproduce what the eye can see, he drew everything he saw around him, including executed criminals hanging on gallows as well as the beauties of nature. Trying to understand how the human body worked, Leonardo studied live and dead bodies, doing autopsies and dissections to investigate muscles and circulation. He carefully analyzed the effects of light, and he experimented with perspective.

Leonardo used his drawings not only as the basis for his paintings but also as a tool of scientific investigation. He drew plans for hundreds of inventions, many of which would become reality centuries later, such as the helicopter, tank, machine gun, and parachute. He was hired by one of the powerful new rulers in Italy, Duke Ludovico Sforza of Milan, to design weapons, fortresses, and water systems, as well as to produce works of art. Leonardo left Milan when Sforza was overthrown, and he spent the last years of his life painting, drawing, and designing for the pope and the French king.

Leonardo experimented with new materials for painting and sculpture, not all of which worked. The experimental method he used to paint The Last Supper caused the picture to deteriorate rapidly, and it began to flake off the wall as soon as it was finished. Leonardo regarded it as never quite completed because he could not find a model for the face of Christ who would evoke the spiritual depth he felt the figure deserved. His gigantic equestrian statue in honor of Ludovico’s father, Duke Francesco Sforza, was never made, and the clay model collapsed. He planned to write books on many subjects but never finished any of them, leaving only notebooks. Leonardo once said that “a painter is not admirable unless he is universal.” The patrons who supported him — and he was supported very well — perhaps wished that his inspirations would have been a bit less universal in scope, or at least accompanied by more perspiration.

Sources: Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists, vol. 1, trans. G. Bull (London: Penguin Books, 1965); S. B. Nuland, Leonardo da Vinci (New York: Lipper/Viking, 2000).

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- In what ways do the labels “genius” and “Renaissance man” both support and contradict each other? Which better fits Leonardo?

- Has the idea of artistic genius changed since the Renaissance? How?

ONLINE DOCUMENT PROJECT

How did the needs and desires of Leonardo’s patrons influence his work? Keeping the question above in mind, examine letters and visual evidence that sheds light on the dynamic between the artist and his employers, and then complete a writing assignment based on the evidence and details from this chapter.

See Document Project for Chapter 12.