What reforms did the Catholic Church make?

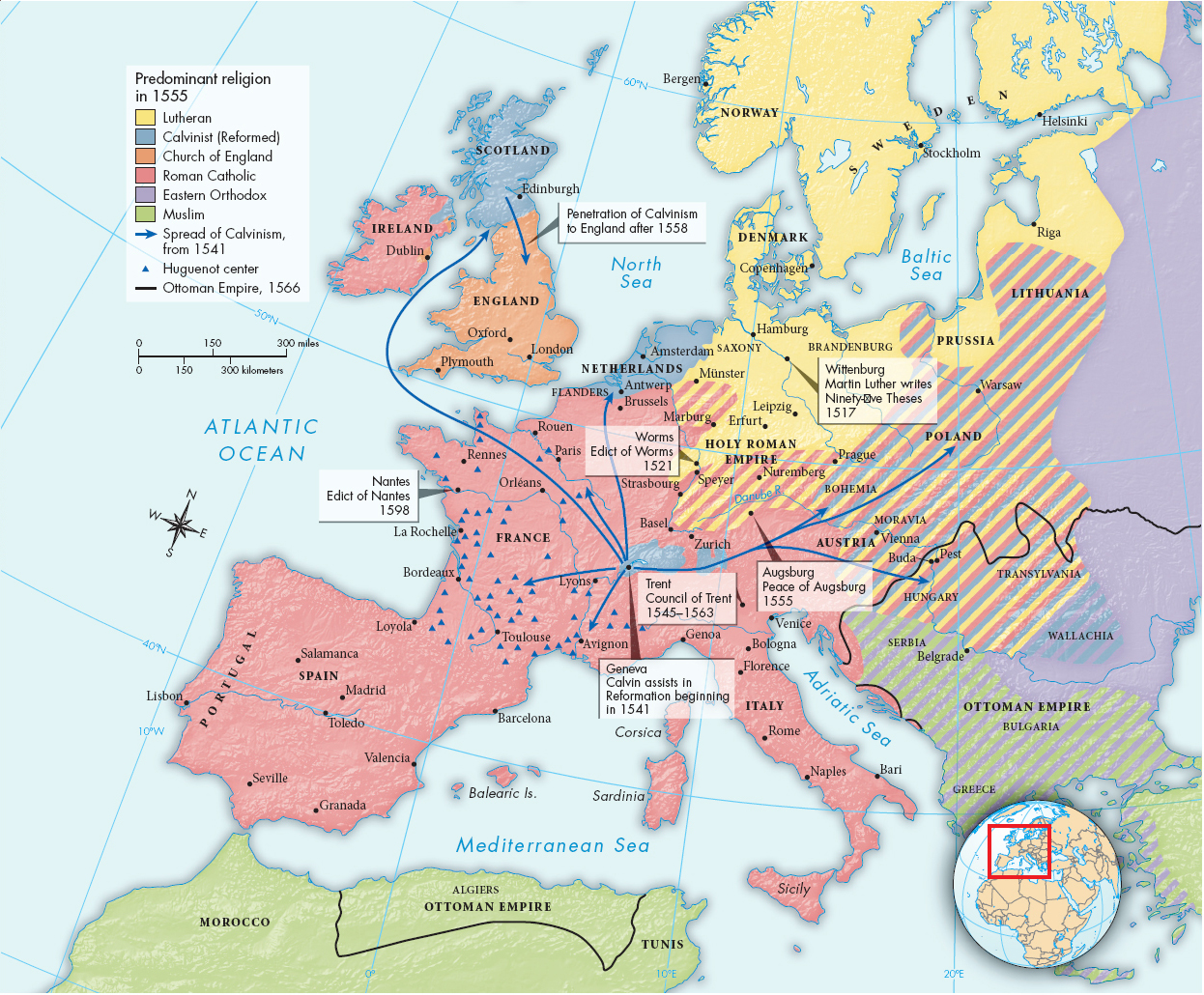

BBETWEEN 1517 AND 1547, Protestantism made remarkable advances. Nevertheless, the Roman Catholic Church made a significant comeback. After about 1540, no new large areas of Europe, other than the Netherlands, accepted Protestant beliefs (Map 13.2). Many historians see the developments within the Catholic Church after the Protestant Reformation as two interrelated movements: one a drive for internal reform linked to earlier reform efforts, the other a Counter-

Church of the GesùBegun in 1568 as the mother church for the Jesuit order, the Church of the Gesù in Rome conveyed a sense of drama, motion, and power through its lavish decorations and shimmering frescoes. Gesù served as a model for Catholic churches elsewhere in Europe and the New World, their triumphant and elaborate style reflecting the dynamic and proselytizing spirit of the Catholic Reformation. (© Alfredo Dagli Orti/The Art Archive/Corbis)

MAP 13.2 Religious Divisions in Europe, ca. 1555The Reformations shattered the religious unity of Western Christendom. The situation was even more complicated than a map of this scale can show. Many cities within the Holy Roman Empire, for example, accepted a different faith than the surrounding countryside; Augsburg, Basel, and Strasbourg were all Protestant, though they were surrounded by territory ruled by Catholic nobles.> MAPPING THE PASTANALYZING THE MAP: Which countries were the most religiously diverse in Europe? Which were the least diverse?

CONNECTIONS: Where was the first arena of religious conflict in sixteenth-

CONNECTIONS: Where was the first arena of religious conflict in sixteenth-