Race and the Enlightenment

If philosophers did not believe the lower classes qualified for enlightenment, how did they regard individuals of different races? In recent years, historians have found in the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment a crucial turning point in European ideas about race. A primary catalyst for new ideas about race was the urge to classify nature, an urge unleashed by the Scientific Revolution’s insistence on careful empirical observation. As scientists developed taxonomies of plant and animal species, they also began to classify humans into hierarchically ordered “races.”

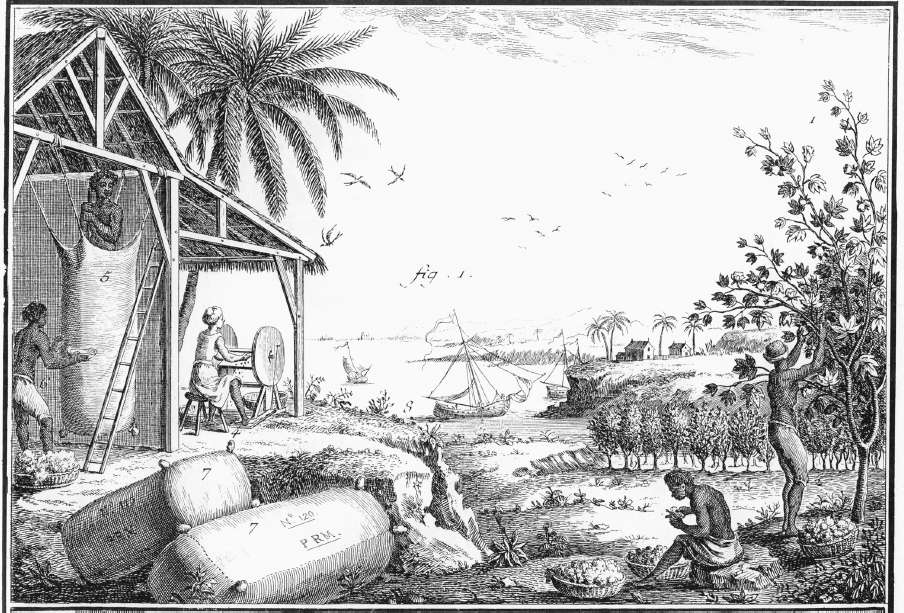

Using the word race to designate biologically distinct groups of humans, akin to distinct animal species, was new. Previously, Europeans grouped other peoples into “nations” based on their historical, political, and cultural affiliations, rather than on supposedly innate physical differences. When European thinkers drew up a hierarchical classification of human species, their own “race” was placed, of course, at the top. Europeans had long believed they were culturally superior. Now emerging ideas about racial difference told them they were biologically superior as well. In turn, scientific racism helped legitimate and justify the tremendous growth of slavery that occurred during the eighteenth century.

Racist ideas did not go unchallenged. The abbé Raynal’s History of the Two Indies (1770) fiercely attacked slavery and the abuses of European colonization. Encyclopedia editor Denis Diderot adopted Montesquieu’s technique of criticizing European attitudes through the voice of outsiders in his dialogue between Tahitian villagers and their European visitors. Scottish philosopher James Beattie (1735–

>QUICK REVIEW

How did Enlightenment thinkers challenge the social, political, and cultural status quo? In what ways did they reinforce it?