Catherine the Great of Russia

Catherine the Great of Russia (r. 1762–1796) was one of the most remarkable rulers of her age, and the French philosophes adored her. Catherine had drunk deeply at the Enlightenment well. Never questioning that absolute monarchy was the best form of government, she set out to rule in an enlightened manner. She had three main goals. First, she worked hard to continue Peter the Great’s effort to bring the culture of western Europe to Russia (see Chapter 15). To do so, she imported Western architects, musicians, and intellectuals. She bought masterpieces of Western art and patronized the philosophes. With these actions, Catherine won good press in the West for herself and for her country. This intellectual ruler, who wrote plays and loved good talk, set the tone for the entire Russian nobility. Peter the Great westernized Russian armies, but it was Catherine who westernized the imagination of the Russian nobility.

Catherine’s second goal was domestic reform, and she began her reign with sincere and ambitious projects. In 1767, she appointed a legislative commission to prepare a new law code. This project was never completed, but Catherine did restrict the practice of torture and allowed limited religious toleration. She also tried to improve education and strengthen local government. The philosophes applauded these measures and hoped more would follow.

Such was not the case. In 1773, a Cossack soldier named Emelian Pugachev sparked a gigantic uprising of thousands of serfs. Proclaiming himself the true tsar, Pugachev issued orders abolishing serfdom, taxes, and army service. Pugachev’s army proved no match for Catherine’s noble-led army, and Pugachev was captured and executed. Pugachev’s rebellion put an end to any intentions Catherine had about reforming the system. In 1785, she freed nobles forever from taxes and state service. Under Catherine, the Russian nobility attained its most exalted position, and serfdom entered its most oppressive phase.

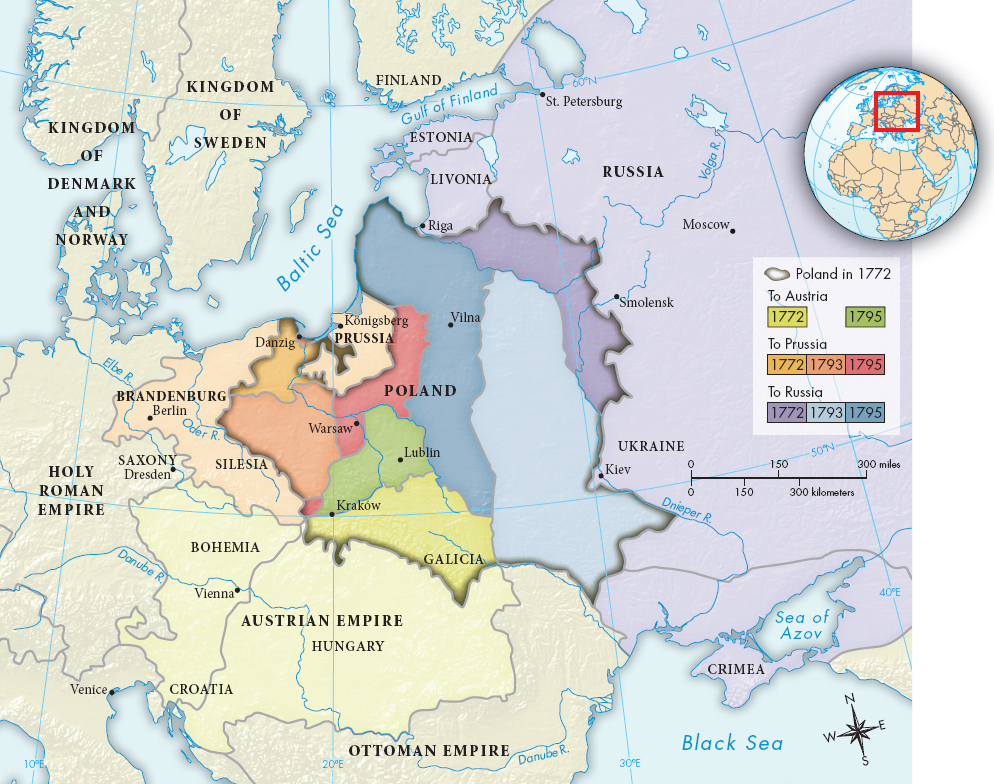

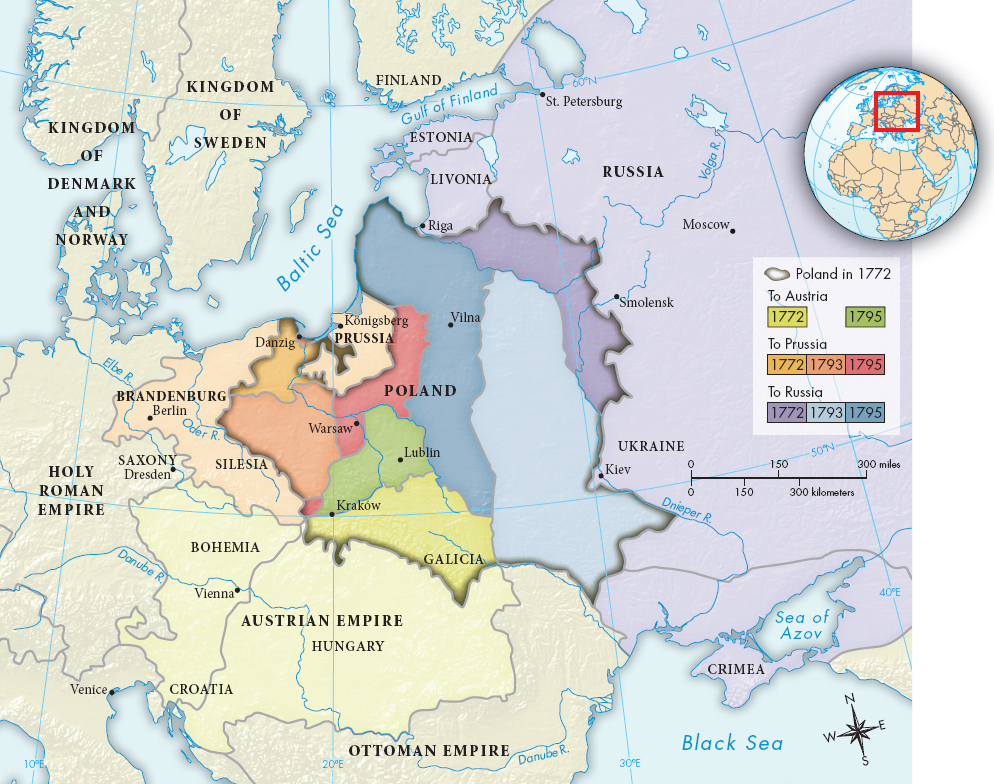

Catherine’s third goal was territorial expansion, and in this respect she was extremely successful. Her armies subjugated the last descendants of the Mongols and the Crimean Tartars, and began the conquest of the Caucasus (KAW-kuh-suhs). Her greatest coup by far was the partition of Poland (Map 16.1). When, between 1768 and 1772, Catherine’s armies scored unprecedented victories against the Ottomans and thereby threatened to disturb the balance of power between Russia and Austria in eastern Europe, Frederick of Prussia obligingly came forward with a deal. He proposed that Turkey be let off easily and that Prussia, Austria, and Russia each compensate itself by taking a gigantic slice of the weakly ruled Polish territory. The first partition of Poland took place in 1772. Subsequent partitions in 1793 and 1795 gave away the rest of Polish territory, and the ancient republic of Poland vanished from the map.

MAP 16.1The Partition of Poland, 1772–1795 In 1772, war between Russia and Austria threatened over Russian gains from the Ottoman Empire. To satisfy desires for expansion without fighting, Prussia’s Frederick the Great proposed that parts of Poland be divided among Austria, Prussia, and Russia. In 1793 and 1795, the three powers partitioned the remainder, and the republic of Poland ceased to exist.> MAPPING THE PASTANALYZING THE MAP: Of the three powers that divided the kingdom of Poland, which gained the most territory? How did the partition affect the geographical boundaries of each state, and what was the significance? What border with the former Poland remained unchanged? Why do you think this was the case?CONNECTIONS: What does it say about European politics at the time that a country could simply cease to exist on the map? Could that happen today?