Leisure and Recreation

Despite the spread of literacy, the culture of the village remained largely oral rather than written. In the cold, dark winter months, peasant families gathered around the fireplace to sing, tell stories, do craftwork, and keep warm. In some parts of Europe, women would gather together in someone’s cottage to chat, sew, spin, and laugh. A favorite recreation of men was drinking and talking with buddies in public places, and it was a sorry village that had no tavern.

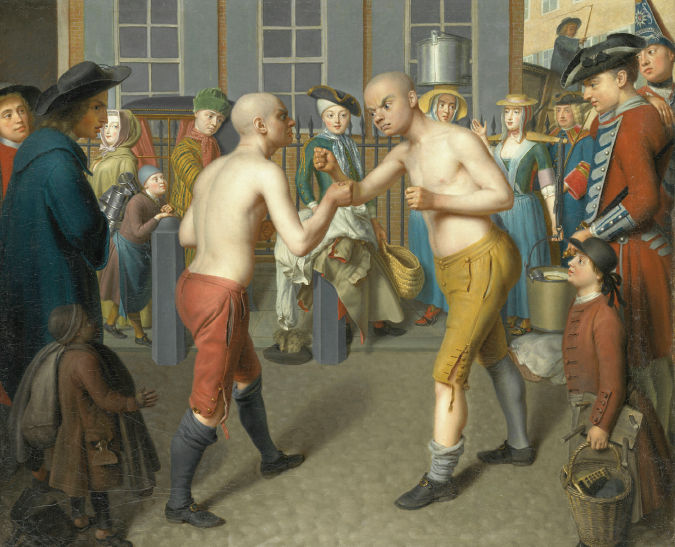

Towns and cities offered a wider range of amusements, including fairs, pleasure gardens, theaters, and lending libraries. Leisure activities were another form of consumption marked by growing commercialization. For example, commercial, profit-

Blood sports, such as bullbaiting and cockfighting, also remained popular with the masses. In bullbaiting, the bull, usually staked on a chain in the courtyard of an inn, was attacked by ferocious dogs for the amusement of the innkeeper’s clients. Eventually the maimed and tortured animal was slaughtered by a butcher and sold as meat. In cockfighting, two roosters slashed and clawed each other in a small ring until the victor won — and the loser died.

Popular recreation merged with religious celebration in a variety of festivals and processions throughout the year. The most striking display of these religiously inspired events was carnival, a time of reveling and excess in Catholic Europe, especially in Mediterranean countries. Carnival preceded Lent — the forty days of fasting and penitence before Easter — and for a few exceptional days in February or March, a wild release of drinking, masquerading, and dancing reigned. In addition, a combination of plays, processions, and raucous spectacles turned the established order upside down. Peasants dressed as nobles and men as women, and rich masters waited on their servants at the table. This annual holiday gave people a chance to release their pent-

In trying to place the vibrant popular culture of the common people in broad perspective, historians have stressed the growing criticism levied against it by the educated elites in the second half of the eighteenth century. These elites, who had previously shared the popular enthusiasm for religious festivals, carnival, drinking in taverns, blood sports, and the like, now tended to see superstition, sin, disorder, and vulgarity in these activities.7 The resulting attack on popular culture, which was tied to the clergy’s efforts to eliminate paganism and superstition, was intensified as an educated public embraced the critical worldview of the Enlightenment.