Technological Innovations and Early Factories

The pressure to produce more goods for a growing market and to reduce the labor costs of manufacturing was directly related to the first decisive breakthrough of the Industrial Revolution: the creation of the world’s first machine-

The putting-

Given this situation, many a tinkering worker knew that a better spinning wheel promised rich rewards. It proved hard to spin the traditional raw materials — wool and flax — with improved machines, but cotton was different. Cotton textiles had first been imported into Britain from India by the East India Company. In the eighteenth century, a lively market for cotton cloth emerged in West Africa, where the English and other Europeans traded it in exchange for slaves. By 1760, a tiny domestic cotton industry had emerged in northern England, but it could not compete with cloth produced by low-

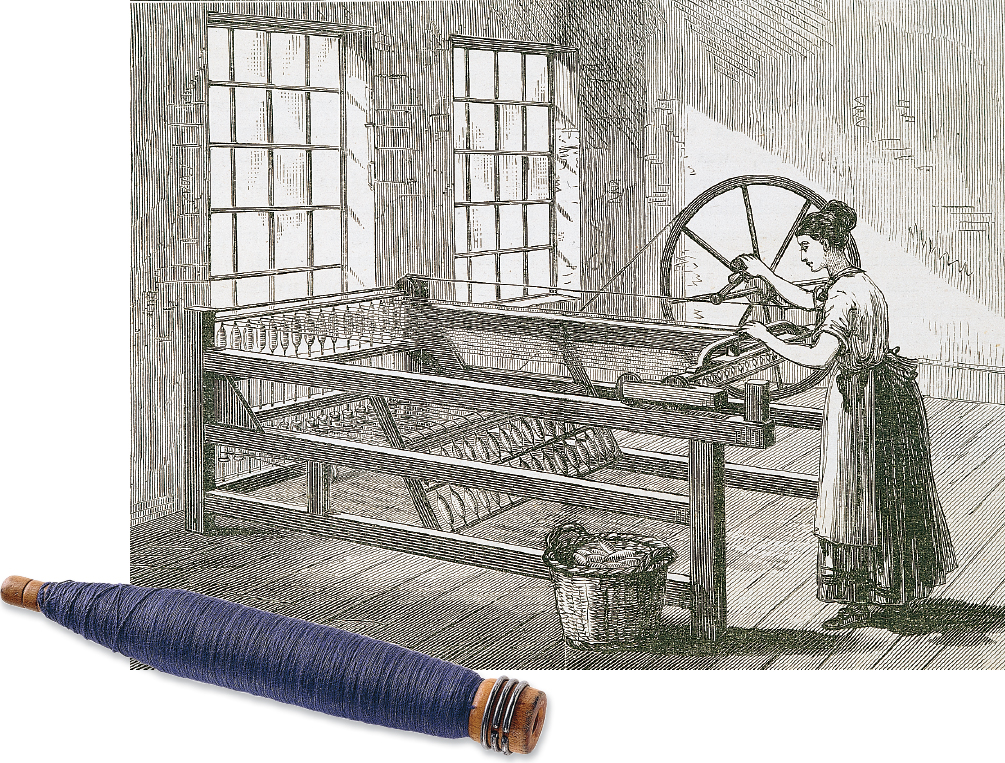

After many experiments over a generation, a gifted carpenter, James Hargreaves, invented his cotton-

Hargreaves’s spinning jenny was simple, inexpensive, and powered by hand. In early models, from six to twenty-

Arkwright’s water frame employed a different principle. It quickly acquired a capacity of several hundred spindles and demanded much more power than a single operator could provide. A solution was found in waterpower. The water frame required large specialized mills to take advantage of the rushing currents of streams and rivers. The factories they powered employed as many as one thousand workers from the very beginning. Gradually, all cotton spinning was concentrated in large-

Despite the significant increases in productivity, the working conditions in the early cotton factories were atrocious. Adult weavers and spinners were reluctant to leave the safety and freedom of work in their own homes to labor in noisy and dangerous factories where the air was filled with cotton fibers. Therefore, factory owners often turned to young orphans and children who had been abandoned by their parents and put in the care of local parishes. Parish officers often “apprenticed” such unfortunate foundlings to factory owners. Such child workers were forced by law to labor for their “masters” for as many as fourteen years. Housed, fed, and locked up nightly in factory dormitories, the young workers labored thirteen or fourteen hours a day for little or no pay. Harsh physical punishment maintained brutal discipline.

The creation of the world’s first machine-