The Distribution of Income

By 1850, at the latest, real wages — that is, wages received by workers adjusted for changes in the prices they paid — were rising for the mass of the population, and they continued to do so until 1914. The real wages of British workers, for example, almost doubled between 1850 and 1906. Ordinary people took a major step forward in the centuries-

Greater economic rewards for the average person did not eliminate hardship and poverty, however; nor did they make the wealth and income of the rich and the poor significantly more equal, as contemporary critics argued and economic historians have clearly demonstrated. The aristocracy retained its position at the very top of the social ladder, followed closely by a new rich elite, composed mainly of the most successful business families from banking, industry, and large-

Income inequality reflected social status. In almost every advanced country around 1900, the richest 5 percent of all households in the population received about a third of all national income, and the richest 20 percent of households received from 50 to 60 percent of it. As a result, the lower 80 percent received only 40 to 50 percent of all income — less than the two richest classes combined. Moreover, the bottom 30 percent of all households received 10 percent or less of all income.

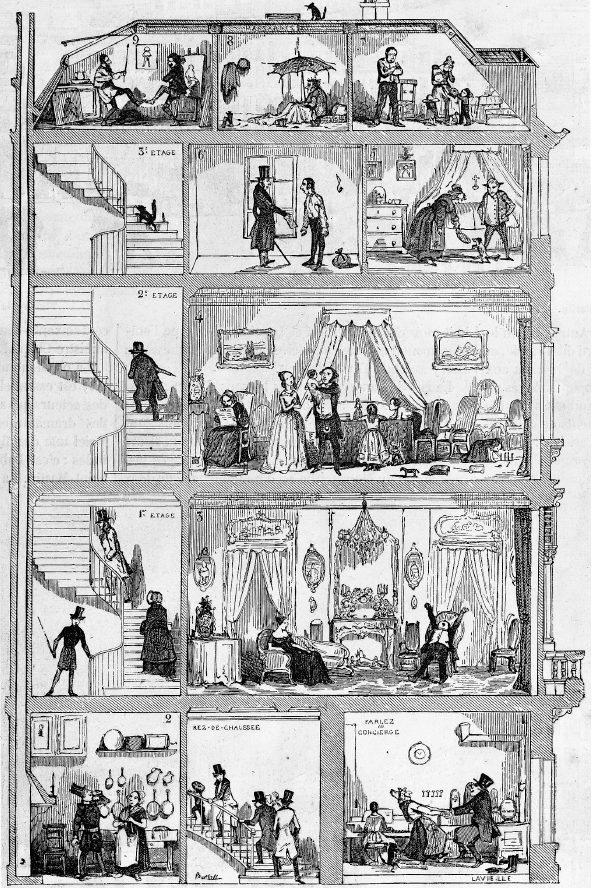

The great gap between rich and poor endured, in part, because industrial and urban development made society more diverse and classes less unified. (See “Picturing the Past: Apartment Living in Paris.”) Society had not split into two sharply defined opposing classes, as Karl Marx had predicted (see "The Birth of Marxist Socialism" in Chapter 21). Instead, the economic specialization that enabled society to produce goods more effectively had created a remarkable variety of new social groups. There developed an almost unlimited range of jobs, skills, and earnings; one group or subclass blended into another in a complex, confusing hierarchy. In this atmosphere of competition and hierarchy, neither the “middle class” nor the “working class” actually acted as a single unified force. Rather, the social and occupational hierarchy developed enormous variations, though the age-

CONNECTIONS: What does this drawing suggest about urban life in the nineteenth century? How might a sketch of a modern, urban American apartment building differ in terms of the types of people who reside in a single building?