Working-Class Leisure and Religion

The urban working classes sought fun and recreation, and they found both. Across Europe, drinking remained unquestionably the favorite leisure-time activity of working people. Generally, however, heavy problem drinking declined in the late nineteenth century as it became less socially acceptable. This decline reflected in part the moral leadership of the labor aristocracy. At the same time, drinking became more publicly acceptable. Cafés and pubs became increasingly bright, friendly places. Working-class political activities, both moderate and radical, were also concentrated in taverns and pubs. Moreover, social drinking in public places by married couples and sweethearts became an accepted and widespread practice for the first time.

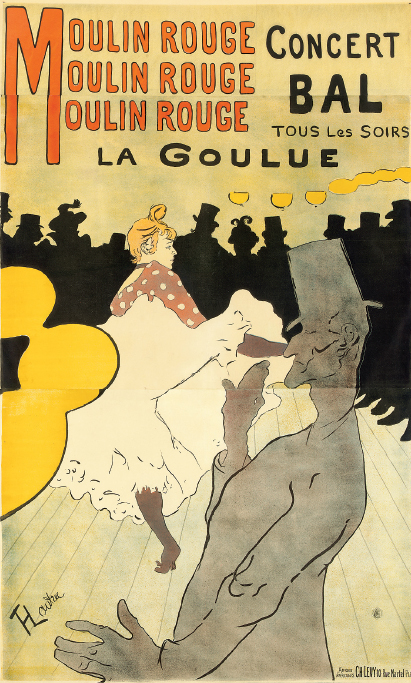

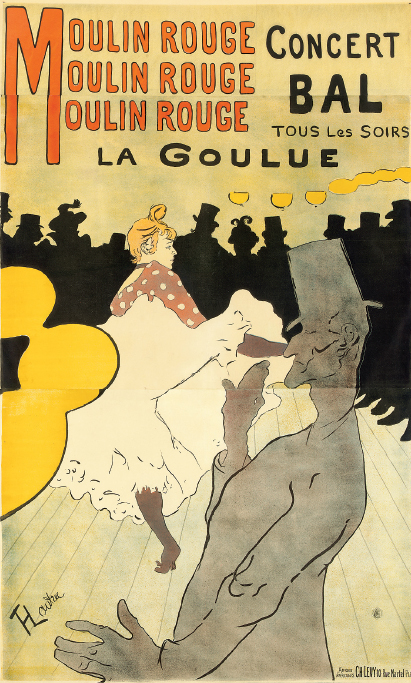

Big City NightlifeThe most famous dance hall and cabaret in Paris was the Moulin Rouge. There La Goulue (“the Glutton”), portrayed on this poster, performed her provocative version of the cancan and reigned as the queen of Parisian sensuality. This is one of many colorful posters done by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901), who combined stupendous creativity and dedicated debauchery in his short life. (Private Collection/Photo © Christie’s Images/The Bridgeman Art Library)

The two other leisure-time passions of working-class culture were sports and music halls. “Cruel sports,” such as bullbaiting and cockfighting, had greatly declined throughout Europe by the late nineteenth century. Commercialized spectator sports filled their place. Working people gambled on sports events, and for many a working person, a desire to decipher racing forms provided a powerful incentive toward literacy. Music halls and vaudeville theaters were enormously popular throughout Europe.

In more serious moments, religion continued to provide working people with solace and meaning. The eighteenth-century vitality of popular religion in Catholic countries and the Protestant rejuvenation exemplified by German Pietism and English Methodism (see "Protestant Revival" in Chapter 18) carried over into the nineteenth century. Indeed, many historians see the early nineteenth century as an age of religious revival. Yet historians recognize that by the last few decades of the nineteenth century, a considerable decline in both church attendance and church donations had occurred in most European countries. And it seems clear that this decline was greater for the urban working classes than for their rural counterparts or for the middle classes.

Why did working-class church attendance decline? On one hand, the construction of churches failed to keep up with the rapid growth of urban population, especially in new working-class neighborhoods. On the other, throughout the nineteenth century, workers saw Catholic and Protestant churches as conservative institutions that defended status quo politics, hierarchical social order, and middle-class morality. As the working classes became more politically conscious, they tended to see established churches as allied with their political opponents. In addition, religion underwent a process historians call “feminization”: in the working and middle classes alike, women were more pious and attended service more regularly than men. Urban workingmen in particular developed vaguely antichurch attitudes, even though they remained neutral or positive toward religion.

What did the emergence of urban industrial society mean for rich and poor and those in between?