Child Rearing

Another striking sign of deepening emotional ties within the family was a growing emphasis on the love and concern that mothers gave their infants. Early emotional bonding and a willingness to make real sacrifices for the welfare of the infant became increasingly important among the comfortable classes by the end of the eighteenth century, though the ordinary mother of modest means adopted new attitudes only as the nineteenth century progressed.

The surge of maternal feeling was shaped by and reflected in a wave of specialized books on child rearing and infant hygiene. Following expert advice, mothers increasingly breast-fed their infants rather than paying wet nurses to do so. Breast-feeding involved sacrifice — a temporary loss of freedom, if nothing else. Yet when there was no good alternative to mother’s milk, it saved lives. Moreover, the practice of swaddling disappeared completely. Instead, ordinary mothers allowed their babies freedom of movement and delighted in their spontaneity.

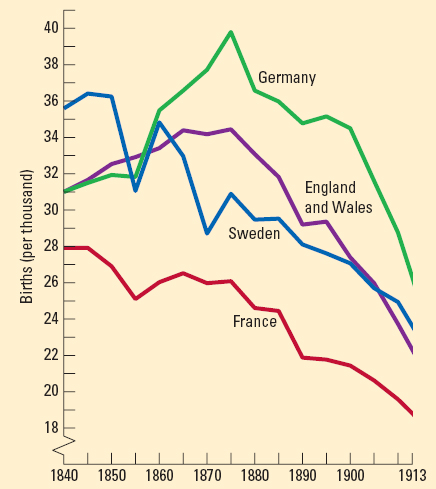

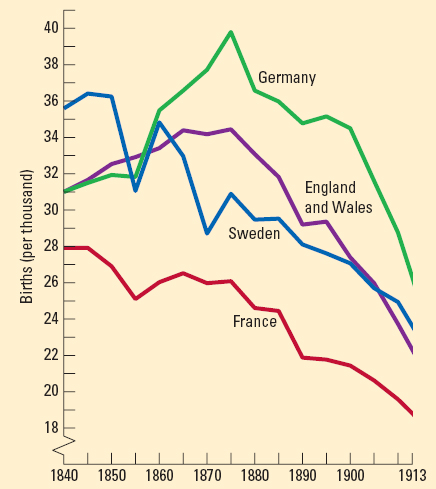

FIGURE 22.2  The Decline of Birthrates in England and Wales, Germany, France, and Sweden, 1840–1913Women had fewer babies for a variety of reasons, including the fact that their children were increasingly less likely to die before reaching adulthood. How does this compare with Figure 22.1?

The Decline of Birthrates in England and Wales, Germany, France, and Sweden, 1840–1913Women had fewer babies for a variety of reasons, including the fact that their children were increasingly less likely to die before reaching adulthood. How does this compare with Figure 22.1?

The loving care lavished on infants was matched by greater concern for older children and adolescents. They, too, were wrapped in the strong emotional ties of a more intimate and protective family. For one thing, European women began to limit the number of children they bore in order to care adequately for those they had. By the end of the nineteenth century, the birthrate was declining across Europe (Figure 22.2), and it continued to do so until after World War II. The Englishwoman who married in the 1860s, for example, had an average of about six children; her daughter marrying in the 1890s had only four; and her granddaughter marrying in the 1920s had only two or possibly three.

The most important reason for this revolutionary reduction in family size, in which the comfortable and well-educated classes took the lead, was parents’ desire to improve their economic and social position and that of their children. Children were no longer an economic asset in the late nineteenth century. By having fewer youngsters, parents could give those they had valuable advantages, from music lessons and summer vacations to long, expensive university educations and suitable dowries. Thus the growing tendency of couples in the late nineteenth century to use a variety of contraceptive methods reflected increased concern for children.

In middle-class households, parents expended considerable effort to ensure that they raised their children according to prevailing family values. Indeed, many parents, especially in the middle classes, probably became too concerned about their children, unwittingly subjecting them to an emotional pressure cooker of almost unbearable intensity. Professional family experts, including teachers, doctors, and reformers, produced a vast popular literature on child rearing that encouraged parents to focus on developing their children’s self-control, self-fulfillment, and sense of Christian morality. Parents carefully monitored their children’s sexual behavior, and masturbation — according to one expert “the most shameful and terrible of all vices” — was of particular concern.4

Attempts to repress the child’s sexuality generated unhealthy tension, often made worse by the rigid division of gender roles within the family. At work all day, the father came home a stranger to his offspring; his world of business was far removed from the maternal world of spontaneous affection. Moreover, the father set demanding rules, often expecting the child to succeed where he himself had failed and making his love conditional on achievement. This kind of distance was the case among mothers as well as fathers in the wealthiest families. Domestic servants, nannies, and tutors did much of the work of child rearing; parents saw their children over dinner, or on special occasions like birthdays or holidays.

The children of the working classes probably had more avenues of escape from such tensions than did those of the middle classes. Unlike their middle-class counterparts, who remained economically dependent on their families until a long education was finished or a proper marriage secured, working-class boys and girls went to work when they reached adolescence. Earning wages on their own, they could bargain with their parents for greater independence within the household by the time they were sixteen or seventeen. If they were unsuccessful in these negotiations, they could and did leave home to live cheaply as paying lodgers in other working-class homes. Not until the twentieth century could middle-class youths be equally free to break away from the family when emotional ties became oppressive.

The Decline of Birthrates in England and Wales, Germany, France, and Sweden, 1840–

The Decline of Birthrates in England and Wales, Germany, France, and Sweden, 1840–