Orientalism

Even though many Westerners shared a sense of superiority over non-Western peoples, they were often fascinated by foreign cultures and societies. In the late 1970s, the influential literary scholar Edward Said (Sie-EED) (1935–2003) coined the term Orientalism to describe this fascination and the stereotypical and often racist Western understandings of non-Westerners that dominated nineteenth-century Western thought.

As Said demonstrated, it was almost impossible for people in the West to look at or understand non-Westerners without falling into some sort of Orientalist stereotype. Politicians, scholarly experts, writers, artists, and ordinary people readily adopted “us versus them” views of foreign peoples. As part of this view of the non-West as radically “other,” Westerners imagined the Orient as a place of mystery and romance, populated with exotic, dark-skinned peoples. (See “Picturing the Past: Orientalism in Art and Everyday Life.”)

| West |

Non-West |

| Modern |

Primitive |

| White |

Colored |

| Christian |

Pagan or Islamic |

Table 24.2: Orientalist Dualities

Such views swept through North American and European scholarship, arts, and literature in the late nineteenth century. The emergence of ethnography and anthropology as academic disciplines in the 1880s was part of the process. Inspired by a new culture of collecting, scholars and adventurers went into the field, where they studied supposedly primitive cultures and acquired artifacts from non-Western peoples. The results of their work were reported in scientific publications, and intriguing objects filled the display cases of new public museums of ethnography and natural history. In a slew of novels published around 1900, authors portrayed romance and high adventure in the colonies and so contributed to the Orientalist worldview. Artists followed suit, and dramatic paintings of ferocious Arab warriors, Eastern slave markets, and the sultan’s harem adorned museum walls and wealthy middle-class parlors. Scholars, authors, and artists were not necessarily racists or imperialists, but they found it difficult to escape Orientalist stereotypes. In the end they helped spread the notions of Western superiority and justified colonial expansion.

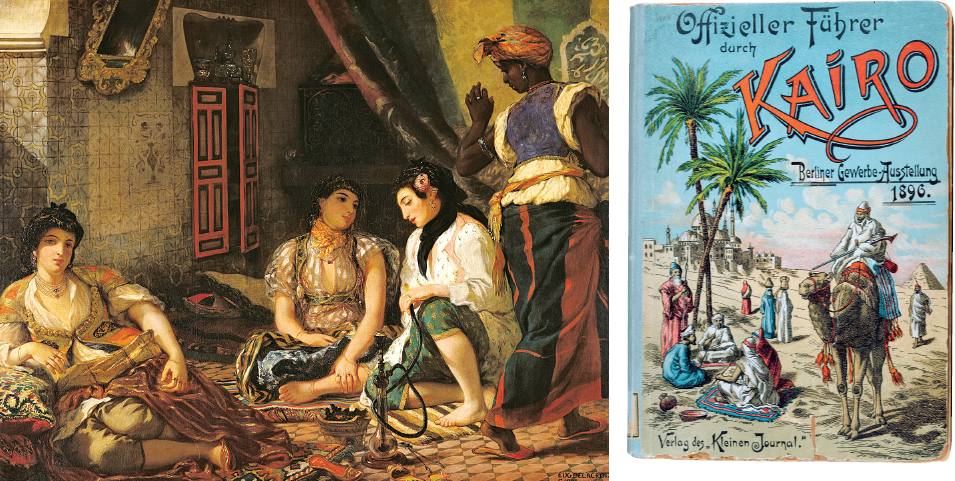

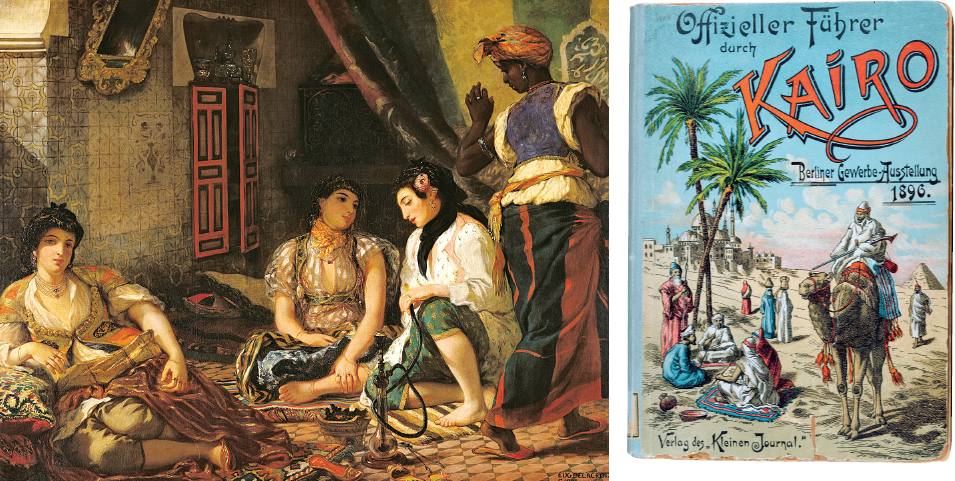

Orientalism in Art and Everyday LifeStereotyped Western impressions of Arabs and the Islamic world became increasingly popular in the West in the nineteenth century. This wave of Orientalism found expression in high art, as in the renowned painting Women of Algiers in Their Apartment (1834), by French painter Eugène Delacroix. Delacroix portrays three women and their African servant at rest in a harem, the segregated, women-only living quarters for the wives of elite Muslim men (Islamic law allows a man to have several wives). Orientalist ideas also made their way into the fabric of everyday life, when ordinary people visited museum exhibits, read newspaper articles, or purchased popular colonial products like cigarettes, coffee, and chocolate. This “Official Guide” to an exhibition on Cairo held in Berlin offers an exotic look at foreign lands. Note the veiled women in the center and the pyramid and desert mosque in the background. (Travel Guide: Private Collection/Archives Charmet/The Bridgeman Art Library; Women of Algiers: Louvre, Paris/Giraudon/The Bridgeman Art Library)> PICTURING THE PASTANALYZING THE IMAGE: What do these representations reveal about Western fascination with Islamic lifestyles and gender roles? How accurate do you think they are?CONNECTIONS: How do images such as these portray Arabs? How would they help spread Orientalist stereotypes?