Stalemate and Slaughter on the Western Front

In the face of the German invasion, the Belgian army slowed the German advance and then fell back in good order to join a rapidly landed British army corps near the Franco-

On September 6 the French attacked a gap in the German line at the Battle of the Marne. For three days, France threw everything into the attack. Finally, the Germans fell back. France had been saved (Map 25.3). With the armies stalled, both sides dug in. By November 1914, an unbroken line of four hundred miles of defensive trenches extended from the Belgian coast through northern France and on to the Swiss frontier. The cost in lives of trench warfare was staggering. For ordinary soldiers, conditions in the trenches were atrocious. Recently invented weapons, the products of an industrial age, made battle impersonal, traumatic, and extremely deadly. The machine gun, hand grenades, poison gas, flamethrowers, long-

The leading generals of the combatant nations struggled to understand trench warfare. For four years, they repeated the same mistakes, mounting massive offensives designed to achieve decisive breakthroughs, failing again and again. In 1916, the unsuccessful German campaign against Verdun cost some 700,000 lives on both sides and ended with the combatants in their original positions. In hard-

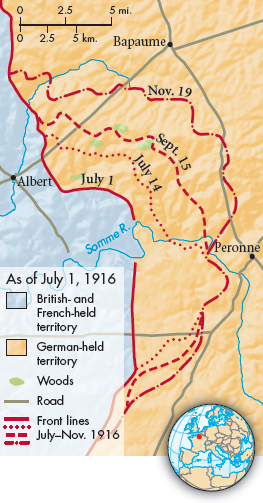

The Battle of the Somme, a great British offensive undertaken in the summer of 1916 in northern France, exemplified the horrors of trench warfare. The battle began with a weeklong heavy artillery bombardment on the German line, intended to cut the barbed wire fortifications, decimate the enemy trenches, and prevent the Germans from making an effective defense. On July 1, the British went “over the top,” climbing out of the trenches and moving into no-

During the bombardment, the Germans had fled to their dugouts — underground shelters dug deep into the trenches. As the British soldiers neared the German lines and the shelling stopped, the Germans emerged from their bunkers, set up their machine guns, and mowed down the approaching troops. In many places, the wire had not been cut by the bombardment, so the attackers, held in place by the wire, made easy targets. About 20,000 British men were killed and 40,000 more were wounded on just the first day. The battle lasted until November, and in the end the British did push the Germans back — a whole seven miles. Some 420,000 British, 200,000 French, and 600,000 Germans were killed or wounded defending an insignificant piece of land.

The anonymous, almost unreal qualities of high-