Germany and the Western Powers

Germany was the key to lasting stability. Yet to Germans of all political parties, the Treaty of Versailles represented a harsh dictated peace, to be revised or repudiated as soon as possible. Germany still had the potential to become the strongest country in Europe but remained a source of uncertainty. Moreover, with ominous implications, France and Great Britain did not see eye to eye on Germany.

Immediately after the war, the French wanted to stress the harsh elements in the Treaty of Versailles. Most of the war in the west had been fought on French soil, and the expected costs of reconstruction, as well as of repaying war debts to the United States, were staggering. Thus French politicians believed that massive reparations from Germany were vital for economic recovery. After having compromised with President Wilson, only to be betrayed by the failure of the U.S. Senate to ratify the treaty, many French leaders saw strict implementation of all provisions of the Treaty of Versailles as France’s last best hope. Large reparation payments could hold Germany down indefinitely, ensuring French security.

The British soon felt differently. Before the war, Germany had been Great Britain’s second-

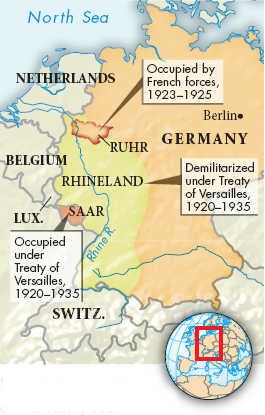

While French and British leaders drifted in different directions, the Allied commission created to determine German reparations completed its work. In April 1921, it announced that Germany had to pay the enormous sum of 132 billion German gold marks (U.S. $33 billion) in annual installments of 2.5 billion gold marks. Facing possible occupation of more of its territory, the young German republic — generally known as the Weimar Republic — made its first payment in 1921. Then in 1922, wracked by rapid inflation and political assassinations, and motivated by hostility and arrogance as well, the Weimar Republic announced its inability to pay more. It proposed a moratorium on reparations for three years, with the clear implication that thereafter reparations would be either drastically reduced or eliminated entirely.

The British were willing to accept a moratorium, but the French, led by their tough-

Strengthened by a wave of German patriotism, the German government ordered the people of the Ruhr to stop working and offer passive resistance to the occupation. The French responded by sealing off the Ruhr and the Rhineland from the rest of Germany, letting in only enough food to prevent starvation.

By the summer of 1923, France and Germany were engaged in a great test of wills. French armies could not collect reparations from striking workers at gunpoint, but the occupation was paralyzing Germany and its economy. To support the striking workers and their employers, the German government began to print money to pay its bills, causing runaway inflation. Prices soared as German money rapidly lost all value. Catastrophic inflation cruelly mocked the old middle-

In August 1923, as the mark lost value and unrest spread throughout Germany, Gustav Stresemann (GOOS-