The Rise of Phoenicia

While Kush expanded in the southern Nile Valley, another group rose to prominence along the Mediterranean coast of modern Lebanon, the northern part of the area called Canaan in ancient sources. These Canaanites established the prosperous commercial centers of Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos, all cities still thriving today, and were master shipbuilders. With their stout ships, between about 1100 and 700 B.C.E. the residents of these cities became the seaborne merchants of the Mediterranean. (See “Primary Source 2.1: The Report of Wenamun.”) Their most valued products were purple and blue textiles, from which originated their Greek name, Phoenicians (fih-NEE-shuhnz), meaning “Purple People.”

The trading success of the Phoenicians brought them prosperity. In addition to textiles and purple dye, they began to manufacture goods for export, such as tools, weapons, and cookware. They worked bronze and iron, which they shipped processed or as ores, and made and traded glass products. Phoenician ships often carried hundreds of jars of wine, and the Phoenicians introduced grape growing to new regions around the Mediterranean, dramatically increasing the wine available for consumption and trade. They imported rare goods and materials, including hunting dogs, gold, and ivory, from Persia in the east and their neighbors to the south. They also expanded their trade to Egypt, where they mingled with other local traders.

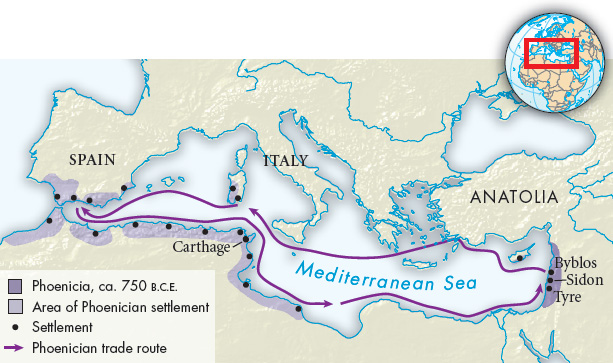

The variety and quality of the Phoenicians’ trade goods generally made them welcome visitors. Moving beyond Egypt, they struck out along the coast of North Africa to establish new markets in places where they encountered little competition. In the ninth century B.C.E. they founded, in modern Tunisia, the city of Carthage (meaning “new city” in Phoenician), which prospered to become the leading city in the western Mediterranean, although it would one day struggle with Rome for domination of that region.

The Phoenicians planted trading posts and small farming communities along the coast, founding colonies in Spain and Sicily along with Carthage. Their trade routes eventually took them to the far western Mediterranean and beyond to the Atlantic coast of modern-day Portugal. The Phoenicians’ voyages brought them into contact with the Greeks, to whom they introduced many aspects of the older and more urbanized cultures of Mesopotamia and Egypt.

The Phoenicians’ overwhelming cultural achievement was the spread of a completely phonetic system of writing — that is, an alphabet. Writers of both cuneiform and hieroglyphics had developed signs that were used to represent sounds, but these were always used with a much larger number of ideograms. Sometime around 1800 B.C.E. workers in the Sinai Peninsula, which was under Egyptian control, began to write only with phonetic signs, with each sign designating one sound. This system vastly simplified writing and reading and spread among common people as a practical way to record things and communicate. Egyptian scribes and officials continued to use hieroglyphics, but the Phoenicians adopted the simpler system for their own language and spread it around the Mediterranean. The Greeks modified this alphabet and then used it to write their own language, and the Romans later based their alphabet — the script we use to write English today — on Greek. Alphabets based on the Phoenician alphabet were also created in the Persian Empire and formed the basis of Hebrew, Arabic, and various alphabets of South and Central Asia. The system invented by ordinary people and spread by Phoenician merchants is the origin of most of the world’s phonetic alphabets today.