Ethnic Diversity in Contemporary Europe

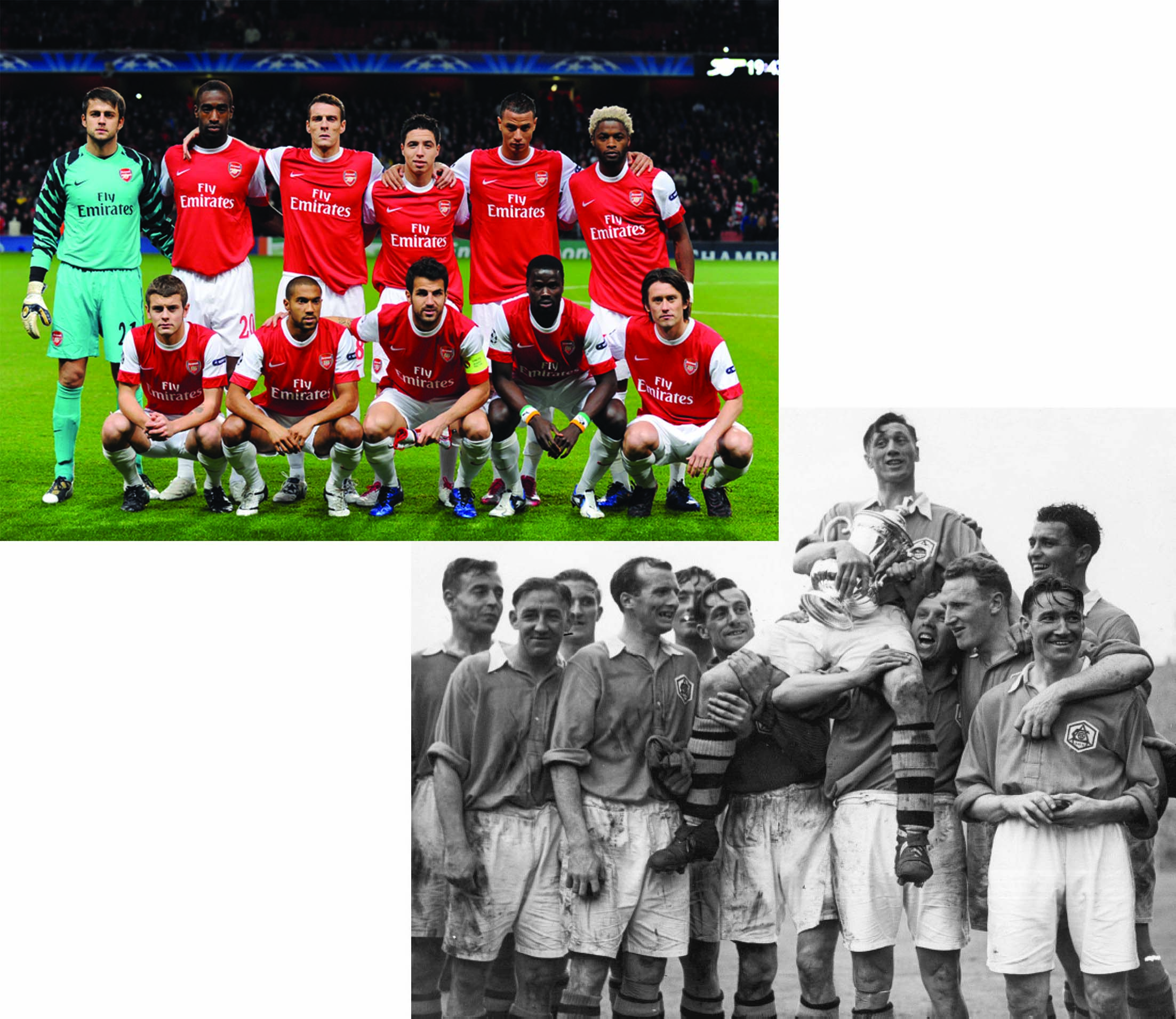

By 2010 immigration to Europe had profoundly changed the ethnic makeup of the continent, though the effects were unevenly distributed. In 2005 immigrants constituted about 10 percent of most western European nations but a far smaller share of the former East Bloc nations. One way to measure the effect of these new immigrants is to consider the rapid rise of their numbers. Since the 1960s the foreign population of western European nations has grown by two to ten times. In the Netherlands in 1960, only 1 percent of the population was foreign born. In 2006 the foreign born made up 10 percent. Over the same years the proportion of immigrants grew from 1.2 to 12.3 percent in Germany and from 4.7 to almost 11 percent in France.6 For centuries the number of foreigners living in Europe had been relatively small. Now, permanently displaced ethnic groups, or diasporas, brought ethnic diversity to the continent.

The new immigrants were divided into two main groups. A small percentage were highly trained specialists who could find work in the upper ranks of education, business, and high-tech industries. Engineers from English-speaking India, for example, could find positions in international computer companies. The mass of immigrants, however, did not have access to high-quality education or language training, which limited their employment opportunities and made integration more difficult. They often lived in separate city districts marked by poor housing and crowded conditions, which set them apart from more established residents. Parts of London were home to tens of thousands of immigrants from the former colonies, and in Paris North Africans dominated some working-class banlieues (suburbs).

A variety of new cultural forms, ranging from sports and cuisine to music, the fine arts, and film, brought together native and foreign traditions and transformed European lifestyles. Food is a case in point. Recipes and cooks from former colonies in North Africa enlivened French cooking, while the döner kebab — the Turkish version of a gyro sandwich — became Germany’s “native” fast food. Indian restaurants proliferated across Britain, and controversy raged when the British foreign minister announced in 2001 that chicken tikka masala — a spicy Indian stew — was Great Britain’s new national dish. In fact, tikka masala is a hybrid, a remarkable example of the way that peoples, recipes, and ingredients from Central Asia, Persia, and Europe had interacted for over four centuries, changing eating habits in Europe and on the Indian subcontinent alike.7

The multiculturalism and ethnic diversity associated with globalization have inspired numerous works in literature, film, and the fine arts. From rap to reggae, multiculturalism has also had a profound effect on popular music, a medium with a huge audience. Rai, which originated in the Bedouin culture of North Africa, exemplifies the new forms that emerged from cultural mixing. In the 1920s rai traveled with Algerian immigrants to France. In its current form, it blends Arab and North African folk music, U.S. rap, and French and Spanish pop styles. Lyrics range from sentimental love stories to blunt and sometimes bawdy descriptions of daily life. The Algerian Cheb Khaled, the unofficial “King of Rai,” has become an international superstar. His song “To Flee, but Where?” captures Khaled’s dismay with collapsing Islamic traditions in Algeria and the burdens of life in the Algerian diaspora in France.

The growth of immigration and ethnic diversity created rich social and cultural interactions but also generated intense controversy and conflict in western Europe. In most EU nations, immigrants can become full citizens if they meet certain legal qualifications; adopting the culture of the host country is not a requirement. This legal process has raised questions about who, exactly, could or should be European, and about the way these new citizens might change European society. The idea that cultural and ethnic diversity could be a force for vitality and creativity has run counter to deep-seated beliefs about national homogeneity. Some commentators have accused the newcomers of taking jobs from unemployed native Europeans and undermining national unity. Government welfare programs intended to support struggling immigrants have been criticized by some as a misuse of money, especially in times of economic downturn.

Immigration is a highly charged political issue. By the 1990s in France, some 70 percent of the population believed that there were “too many Arabs,” and 30 percent supported right-wing politician Jean-Marie Le Pen’s calls to rid France of its immigrants altogether. Even then-future president Jacques Chirac could claim in 1991 that he understood that good French workers could be driven “understandably crazy” by the “noise and smell” of foreigners in the country.8 Le Pen’s National Front and far-right political parties elsewhere, such as the Danish People’s Party and Austria’s Freedom Party, successfully exploited popular prejudice about what they called “foreign rabble” to make impressive gains in national elections. (See “Primary Source 30.3: National Front Campaign Poster.”)