Individuals in Society: Meister Eckhart

342

Meister Eckhart

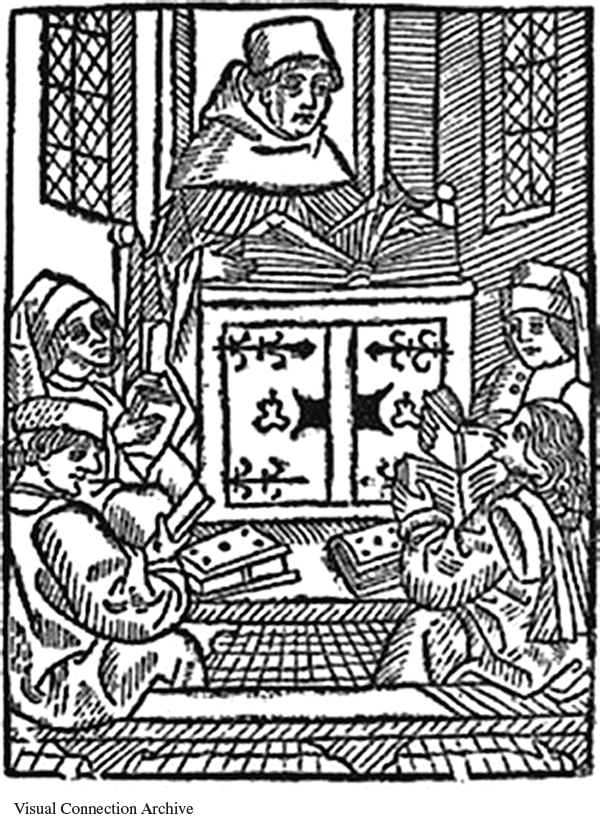

M ysticism — the direct experience of the divine — is an aspect of many world religions and has been part of Christianity throughout its history. During the late Middle Ages, however, the pursuit of mystical union became an important part of the piety of many laypeople, especially in the Rhineland area of Germany. In this they were guided by the sermons of the churchman generally known as Meister Eckhart. Born into a German noble family, Eckhart (1260–1329?) joined the Dominican order and studied theology at Paris and Cologne, attaining the academic title of “master” (Meister in German). The leaders of the Dominican order appointed him to a series of administrative and teaching positions, and he wrote learned treatises in Latin that reflected his Scholastic training and deep understanding of classical philosophy.

He also began to preach in German, attracting many listeners through his beautiful language and mystical insights. God, he said, was “an oversoaring being and an overbeing nothingness,” whose essence was beyond the ability of humans to express: “if the soul is to know God, it must know Him outside time and place, since God is neither in this or that, but One and above them.” Only through “unknowing,” emptying oneself, could one come to experience the divine. Yet God was also present in individual human souls, and to a degree in every creature, all of which God had called into being before the beginning of time. Within each human soul there was what Eckhart called a “little spark,” an innermost essence that allows the soul — with God’s grace and Christ’s redemptive action — to come to God. “Our salvation depends upon our knowing and recognizing the Chief Good which is God Himself,” preached Eckhart; “the Eye with which I see God is the same Eye with which God sees me.” “I have a capacity in my soul for taking in God entirely,” he went on, a capacity that was shared by all humans, not only members of the clergy or those with special spiritual gifts. Although Eckhart did not reject church sacraments or the hierarchy, he frequently stressed that union with God was best accomplished through quiet detachment and simple prayer rather than pilgrimages, extensive fasts, or other activities: “If the only prayer you said in your whole life was ‘thank you,’ that would suffice.”*

Eckhart’s unusual teachings led to charges of heresy in 1327, which he denied. The pope — who was at this point in Avignon — presided over a trial condemning him, but Eckhart appears to have died during the course of the proceedings or shortly thereafter. His writings were ordered destroyed, but his followers preserved many and spread his teachings.

In the last few decades, Meister Eckhart’s ideas have been explored and utilized by philosophers and mystics in Buddhism, Hinduism, and neo-

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- Why might Meister Eckhart’s preaching have been viewed as threatening by the leaders of the church?

- Given the situation of the church in the late Middle Ages, why might mysticism have been attractive to pious Christians?