Spain’s Voyages to the Americas

436

We now know that Christopher Columbus was not the first to explore the Atlantic. Ninth-

A native of the port city of Genoa, Christopher Columbus was early on drawn to the life of the sea. He became an experienced seaman and navigator and worked as a mapmaker in Lisbon. He was familiar with portolans — written descriptions of the courses along which ships sailed — and the use of the compass for dead reckoning. (He carried an astrolabe on his first voyage, but did not use it for navigation.) As he asserted in his journal: “I have spent twenty-

437

Columbus was also a deeply religious man. He had witnessed the Spanish conquest of Granada and shared fully in the religious and nationalistic fervor surrounding that event. Like the Spanish rulers and most Europeans of his age, Columbus understood Christianity as a missionary religion that should be carried to all places of the earth. He viewed himself as a divine agent: “God made me the messenger of the new heaven and the new earth of which he spoke in the Apocalypse of St. John . . . and he showed me the post where to find it.”12

Rejected for funding by the Portuguese in 1483 and by Ferdinand and Isabella in 1486, Columbus’s project to find a westward passage to the Indies finally won the backing of the Spanish monarchy in 1492. Buoyed by the success of the reconquista and eager to earn profits from trade, the Spanish crown named Columbus viceroy over any territory he might discover and promised him one-

Columbus and his small fleet left Spain on August 3, 1492. Inspired by the stories of Mandeville and Marco Polo, Columbus dreamed of reaching the court of the Mongol emperor, the Great Khan (not realizing that the Ming Dynasty had overthrown the Mongols in 1368). Based on Ptolemy’s Geography and other texts, he expected to pass the islands of Japan and then land on the east coast of China.

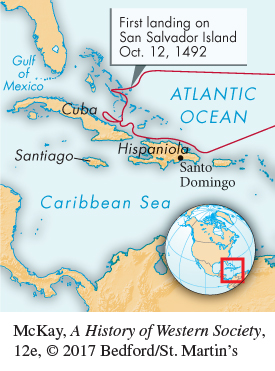

After a brief stop in the Canary Islands, he landed in the Bahamas, which he christened San Salvador, on October 12, 1492. In a letter he wrote to Ferdinand and Isabella on his return to Spain, Columbus described the natives as handsome, peaceful, and primitive people whose body painting reminded him of that of the Canary Islands natives. Believing he was somewhere off the east coast of Japan, in what he considered the Indies, he called them “Indians,” a name later applied to all inhabitants of the Americas. Columbus concluded that they would make good slaves and could easily be converted to Christianity. (See “Evaluating the Evidence 14.1: Columbus Describes His First Voyage.”)

Scholars have identified the inhabitants of the islands as the Taino people, speakers of the Arawak language, who inhabited Hispaniola (modern-

On his second voyage, Columbus forcibly subjugated the island of Hispaniola and enslaved its indigenous peoples. On this and subsequent voyages, Columbus brought with him settlers for the new Spanish territories, along with agricultural seed and livestock. Columbus himself, however, had limited skills in governing. Revolt soon broke out against him and his brother on Hispaniola. A royal expedition sent to investigate returned the brothers to Spain in chains, and a royal governor assumed control of the colony.

Columbus was very much a man of his times. To the end of his life in 1506, he believed that he had found small islands off the coast of Asia. He never realized the scope of his achievement: he had found a vast continent unknown to Europeans, except for a fleeting Viking presence centuries earlier. He could not know that the scale of his discoveries would revolutionize world power and set in motion a new era of trade, empire, and human migration.