Individuals in Society: Samuel Crompton

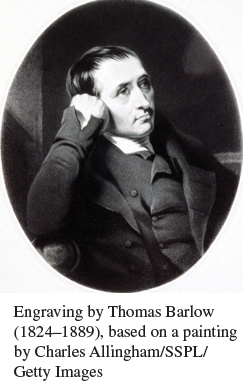

Samuel Crompton

654

S amuel Crompton’s life story illustrates the remarkable ingenuity and determination of the first generation of inventors of the Industrial Revolution as well as the struggles they faced in controlling and profiting from their inventions. Crompton was born in 1753 in Bolton-

Crompton’s mother was a pious and energetic woman who supported the family by tenant farming and spinning and weaving cotton. Crompton spent years spinning in childhood until he was old enough to begin weaving. His mother ensured that he was well educated at the local school, and as a teenager he attended night classes, studying algebra, mathematics, and trigonometry.

This was the period when John Kay’s invention of the flying shuttle doubled the speed of handloom weaving, leading to a drastic increase in the demand for thread (see Chapter 17). Crompton’s family acquired one of the new spinning jennies — invented by James Hargreaves — and he saw for himself how they advanced production. He was also acquainted with Richard Arkwright, inventor of the water frame, who then operated a barbershop in Bolton.

In 1774 Crompton began work on the spinning machine that would consume what little free time, and spare money, he possessed over the next five years. Solitary by nature, and fearful of competition and the violence of machine breakers, Crompton worked alone and in secret. He earned a little extra money playing violin in the Bolton theater orchestra, and he possessed a set of tools left over from his father’s own mechanical experiments.

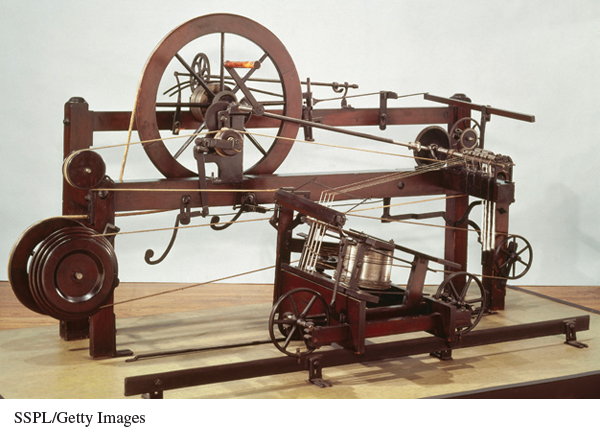

The result of all this effort was the spinning mule, so called because it combined the rollers of Arkwright’s water frame with the moving carriage of Hargreaves’s spinning jenny. With the mule, spinners could produce very fine and strong thread in large quantities, something no previous machine had permitted. The mule effectively ended England’s reliance on India for the finest muslin cloth.

In 1780, possessed of a spectacular technological breakthrough and a beloved bride, Crompton seemed poised for a prosperous and happy life. Demand surged for the products of his machine, and manufacturers were desperate to learn its secrets. Too poor and naïve to purchase a patent for his invention, Crompton shared it with manufacturers through a subscription agreement. Unfortunately, he received little of the promised money in return.

Once exposed to the public, the spinning mule quickly spread across Great Britain. Crompton continued to make high-

As others earned great wealth with the mule, Crompton grew frustrated by his relative poverty. In 1811 he toured Great Britain to document his invention’s impact. He estimated that 4,600,000 mules were then in operation that directly employed 70,000 people. Crompton’s supporters took these figures to Parliament, which granted him a modest reward of £5,000. However, this boost did little to improve his fortunes, and his subsequent business ventures failed. In 1824 local benefactors took up a small subscription to provide for his needs, but he died in poverty in 1827 at the age of seventy-

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- What factors in Crompton’s life enabled him to succeed as an inventor?

- Why did Crompton fail to profit from his inventions?

- What does the contrast between Richard Arkwright’s fantastic success and Crompton’s relative failure tell us about innovation and commercial enterprise in the Industrial Revolution?

Source: Gilbert James France, The Life and Times of Samuel Crompton, Inventor of the Spinning Machine Called the Mule (London: Simpkin Marshall, 1859).