Middle-Class Culture and Values

Despite growing occupational diversity and conflicting interests, lifestyle preferences loosely united the European middle classes. Food, housing, clothes, and behavior all expressed middle-class values and testified to the superior social standing of this group over the working classes.

Unlike the working classes, the middle classes had the money to eat well, and spent a substantial portion of their household budget on food and entertainment. They consumed meat in abundance: a well-off family might spend 10 percent of its annual income on meat and fully 25 percent on food and drink. The dinner party — a favored social occasion — boosted spending. A wealthy middle-class family might give a lavish party for eight to twelve almost every week, and such parties were especially common on holidays.

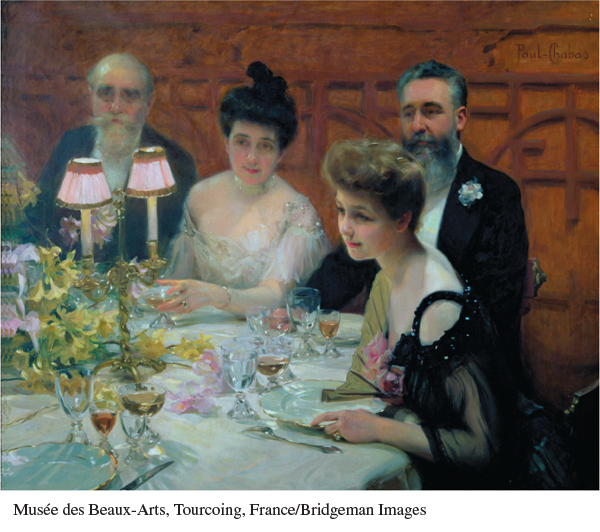

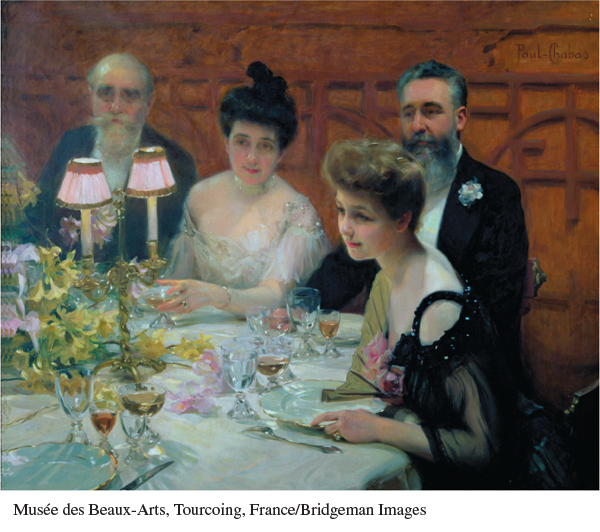

A Corner of the Table (1904) With photographic precision, the French artist Paul-Émile Chabas (1869–1937) captures the elegance and intimacy of a sumptuous dinner party. Throughout Europe, members of the upper middle class and aristocracy enjoyed dinners like this with eight or nine separate courses, beginning with appetizers and ending with coffee and liqueurs.

(Musée des Beaux-Arts, Tourcoing, France/Bridgeman Images)

The middle-class wife could cope with this endless procession of meals, courses, and dishes because she had servants as well as money at her disposal. Indeed, the employment of at least one full-time maid to cook and clean was the clearest sign that a family had crossed the cultural divide separating the working classes from what some contemporary observers called the “servant-keeping classes.” The greater a family’s income, the greater the number of servants it employed. Servants absorbed about another 25 percent of income at all levels of the middle class.

Well fed and well served, the middle classes were also well housed by 1900. Many prosperous families rented, rather than owned, their homes, complete with tiny rooms for servants in the basement or under the eaves of the top floor. And, just as the aristocracy had long divided the year between palatial country estates and lavish townhouses during “the season,” so the upper middle class purchased country places or built beach houses for weekend and summer use.

The middle classes paid great attention to outward appearances, especially their clothes. The factory, the sewing machine, and the department store had all helped reduce the cost and expand the variety of clothing. Middle-class women were particularly attentive to the dictates of fashion, though men also wore the now-appropriate business suit. (See “Living in the Past: Nineteenth-Century Women’s Fashion.”) Ownership of private coaches and carriages, expensive items in the city, further testified to rising social status.

Rich Europeans could devote more time to “culture” and leisure pursuits than less wealthy or well-established families could. The keystones of culture and leisure were books, music, and travel. The long Realist novel, the heroic operas of composers Wagner and Verdi, the diligent striving of the dutiful daughter at the piano, and the packaged tour to a foreign country were all sources of middle-class pleasure.

In addition to their material tastes, the middle classes generally agreed upon a strict code of behavior, manners, and morality. They stressed hard work, self-discipline, and personal achievement. Middle-class social reformers denounced drunkenness and gambling as vices and celebrated sexual purity and fidelity as virtues, especially for women. Men and women who fell into vice, crime, or poverty were held responsible for their own circumstances. A stern sense of Christian morals, preached tirelessly by religious leaders, educators, and politicians, reaffirmed these values. The middle-class individual was supposed to know right from wrong and act accordingly.