The “Great Reforms” in Russia

In the 1850s Russia was a poor agrarian society with a rapidly growing population. Almost 90 percent of the people lived off the land, and industrialization developed slowly. (See “Living in the Past: Peasant Life in Post-Reform Russia.”) Bound to the lord from birth, the peasant serf was little more than a slave, and by the 1840s serfdom had become a central moral and political issue for the government. The slow pace of modernization encouraged the growth of protest movements, from radical Marxists clamoring for socialist revolution to middle-

The Crimean War (1853–1856) grew out of the breakdown of the European balance of power established at the Congress of Vienna (see Chapter 21), general Great Power competition over the Middle East, and Russian desires to expand into the European territories of the Ottoman Empire. A Russian-

The war convinced Russia’s leaders that they had fallen behind the industrializing nations of western Europe. At the very least, Russia needed railroads, better armaments, and military reform to remain a Great Power. Moreover, the disastrous war raised the specter of massive peasant rebellion, making reform of serfdom imperative. Military disaster forced liberal-

767

In a bold move, Alexander II abolished serfdom in 1861. About 22 million emancipated peasants received citizenship rights and the chance to purchase, on average, about half of the land they cultivated. Yet they had to pay fairly high prices, and because the land was to be owned collectively, each peasant village was jointly responsible for the payments of all the families in the village. Collective ownership made it difficult for individual peasants to improve agricultural methods or leave their villages. Thus old patterns of behavior predominated, limiting the effects of reform.

Most of Alexander II’s later reforms were also halfway measures. In 1864 the government established a new institution of local government, the zemstvo. Members of this local assembly were elected by a three-

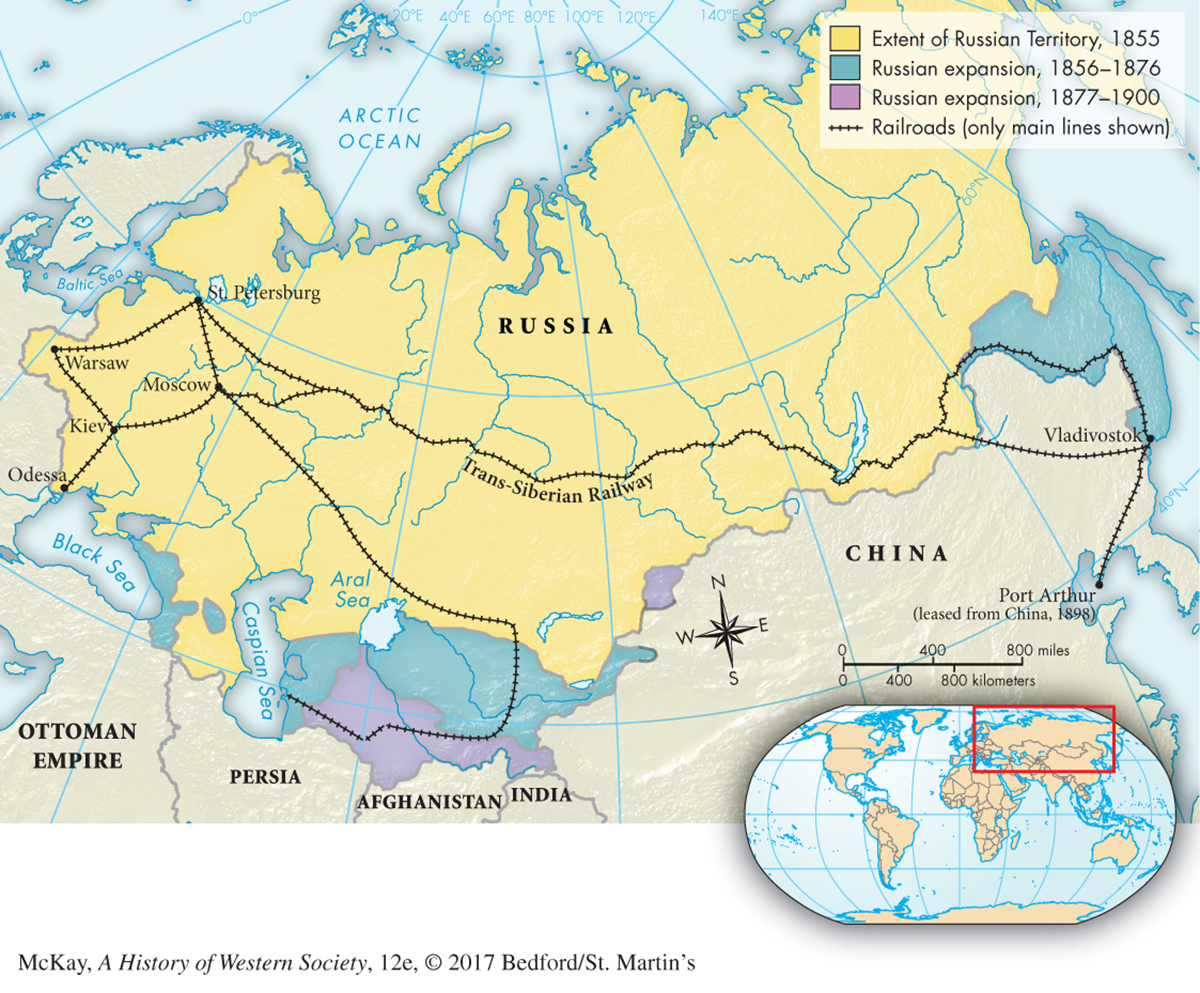

Russian efforts to promote economic modernization proved more successful. Transportation and industry, both vital to the military, were transformed in two industrial surges. The first came after 1860, when the government encouraged and subsidized private railway companies. The railroads linked important cities in the western territories of the empire and enabled Russia to export grain and thus earn money to finance further development. The jewel in the crown of the Russian rail system was the 5,700-

770

Strengthened by industrial development, Russia began to expand by seizing lands on the borders of the empire. Russia took control of territory in far eastern Siberia, on the border with China, and in Central Asia, north of Afghanistan. The imperial state also encroached upon the Islamic lands of the Caucasus, along the northeast border of the Ottoman Empire. Russian peasants, always hungry for land, used the new rail systems to move to and settle in the newly colonized areas, at times displacing local residents (see Map 23.4). The rapid expansion of the Russian Empire to the south and east excited ardent Russian nationalists and superpatriots, who became some of the government’s most enthusiastic supporters. Alexander II consolidated imperial control by suppressing nationalist movements among Poles, Ukrainians, and Baltic peoples in the western lands of the Russian Empire. By 1900 the Russian Empire commanded a vast and diverse array of peoples and places.

Alexander II’s political reforms outraged reactionaries but never went far enough for liberals and radicals. In 1881 a member of the “People’s Will,” a small anarchist group, assassinated the tsar, and the era of reform came to an abrupt end. The new tsar, Alexander III (r. 1881–1894), was a determined reactionary. Nevertheless, from 1890 to 1900 economic modernization and industrialization surged ahead for the second time, led by Sergei Witte (suhr-

Witte’s greatest innovation was to use Westerners to catch up with the West. He encouraged foreigners to build factories in Russia, believing that “the inflow of foreign capital is . . . the only way by which our industry will be able to supply our country quickly with abundant and cheap products.”1 His efforts to entice western Europeans to locate their factories in Russia were especially successful in southern Russia. There, in eastern Ukraine, foreign entrepreneurs and engineers built an enormous and very modern steel and coal industry. In 1900 peasants still constituted the great majority of the population, but Russia was catching up with the more industrialized West.