The Peace Settlement in the Middle East

Although Allied leaders at Versailles focused mainly on European issues, they also imposed a political settlement on what had been the Ottoman Empire. Their decisions, made in Paris and at other international conferences, brought radical and controversial changes to the region. The Allies dismantled or partitioned the Ottoman Empire, Britain and France expanded their influence in the region, Jewish peoples were promised a “national homeland” in British-controlled Palestine, and Arab nationalists felt cheated and betrayed.

The British government had encouraged the wartime Arab revolt against the Ottoman Turks and had even made vague promises of an independent Arab kingdom, most clearly in the McMahon-Hussein correspondence (see “The Widening War”). However, when the fighting stopped, the British and the French chose instead to honor their own secret wartime agreements to divide and rule the Ottoman lands. Most important was the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916, named after the British and French diplomats who negotiated the deal.

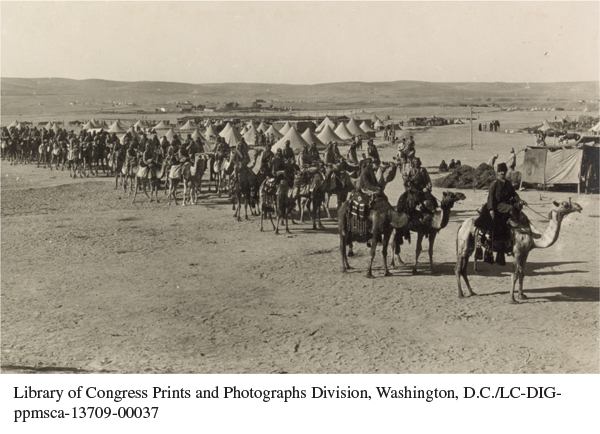

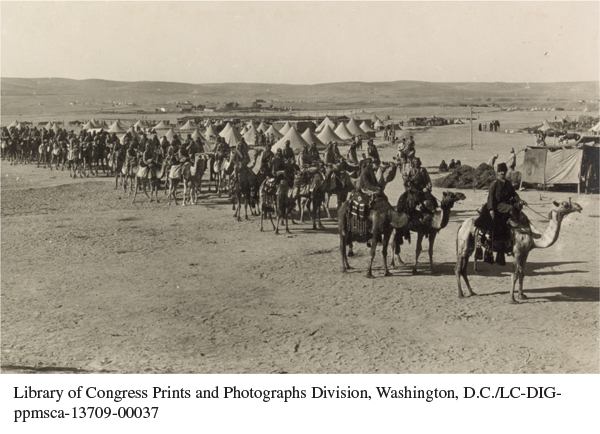

The War in the Middle East An Ottoman camel corps prepares for action in the Sinai Peninsula in 1915. The defeat of the Ottoman Empire in the First World War helped shape the modern Middle East as we know it today.

(Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C./LC-DIG-ppmsca-13709-00037)

In the secret accord, Britain and France agreed that former Ottoman territories would be administered by the European powers under what they called the mandate system. Under the terms of the mandates, individually granted to European powers by the League of Nations, former Ottoman territories (and former German colonies) would be placed under the “tutelage” of European authorities until they could “stand alone.” France would receive a mandate to govern modern-day Lebanon and Syria and much of southern Turkey, and Britain would control Palestine, Transjordan, and Iraq. Though the official goal of the mandate system was to eventually grant these regions national independence, it quickly became clear that the Allies hardly intended to do so. Critics labeled the system colonialism under another name, and when Britain and France set about implementing their agreements after the armistice, Arab nationalists reacted with understandable surprise and resentment.

British plans for the former Ottoman lands that would become Palestine further angered Arab nationalists. The Balfour Declaration of November 1917, written by British foreign secretary Arthur Balfour, had announced that Britain favored a “National Home for the Jewish People” in Palestine, but without discriminating against the civil and religious rights of the non-Jewish communities already living in the region. Some members of the British cabinet believed the declaration would appeal to German, Austrian, and American Jews and thus help the British war effort. Others sincerely supported the Zionist vision of a Jewish homeland (see Chapter 23), which they hoped would also help Britain maintain control of the Suez Canal. Whatever the motives, the declaration enraged Arabs.

In 1914 Jews accounted for about 11 percent of the population in the three Ottoman districts that the British would lump together to form Palestine; the rest of the population was predominantly Arab. Both groups understood that Balfour’s “National Home” implied the establishment of some kind of Jewish state that would violate majority rule. Moreover, a state founded on religious and ethnic exclusivity was out of keeping with Islamic and Ottoman tradition, which had historically been more tolerant of religious diversity and minorities than Christian Europe had been.

Though Arab leaders attended the Versailles Peace Conference, their efforts to secure autonomy in the Middle East came to nothing. Only the kingdom of Hejaz — today part of Saudi Arabia — was granted independence. In response, Arab nationalists came together in Damascus as the General Syrian Congress in 1919 and unsuccessfully called again for political independence. The congress proclaimed Syria an independent kingdom; a similar congress declared Iraqi independence.

The Western reaction was swift and decisive. A French army stationed in Lebanon attacked Syria, taking Damascus in July 1920. The Arab government fled, and the French took over. Meanwhile, the British bloodily put down an uprising in Iraq and established control there. Brushing aside Arab opposition, the British mandate in Palestine formally incorporated the Balfour Declaration and its commitment to a Jewish national home. Western imperialism, in the form of the mandate system authorized by the League of Nations, appeared to have replaced Ottoman rule in the Middle East. In the following decades, deadly anti-imperial riots and violent conflicts between Arabs and Jews would repeatedly undermine the region’s stability. (See “Thinking Like a Historian: The Partition of the Ottoman Empire and the Mandate System.”)

The Allies sought to impose even harsher terms on the defeated Turks than on the “liberated” Arabs. A treaty forced on the Ottoman sultan dismembered the Turkish heartland. Great Britain and France occupied parts of modern-day Turkey, and Italy and Greece claimed shares. There was a sizable Greek minority in western Turkey, and Greek nationalists wanted to build a modern Greek empire modeled on long-dead Byzantium. In 1919 Greek armies carried by British ships landed on the Turkish coast at Smyrna (SMUHR-nuh; today’s Izmir) and advanced unopposed into the interior, while French troops moved in from the south. Turkey seemed finished.

Turkey survived the postwar invasions. A Turkish National Movement emerged, led by Mustafa Kemal (1881–1938), a prominent general in the successful Turkish defeat of the British at the Battle of Gallipoli. The leaders of the movement overthrew the sultan and refused to acknowledge the Allied dismemberment of their country. Under Kemal’s direction, a revived Turkish army gradually mounted a forceful resistance, and despite staggering losses, his troops repulsed the invaders. The Greeks and British sued for peace. In 1923, after long negotiations, the resulting Treaty of Lausanne (loh-ZAN) recognized the territorial integrity of Turkey and solemnly abolished the hated capitulations that the European powers had imposed over the centuries to give their citizens special privileges in the Ottoman Empire.

The peace accords included an agreement for a shattering example of what we would now call “ethnic cleansing,” under which Greeks were forced to leave Turkish-majority lands for Greece, while Turks moved from Greece and former Balkan territories to the Turkish mainland. The result, driven by ideals of national self-determination and racial purity, was a humanitarian disaster. Ethnic Greeks constituted about 16 percent of the Turkish population, and now between 1.5 and 2 million people had to pick up and move west. At the same time, 500,000 to 600,000 ethnic Turks moved out of Greece and Bulgaria to the Anatolian peninsula (modern-day Turkey). Very few wanted to leave their homes, and though the authorities set up refugee camps, refugees faced harsh conditions, rampant looting, and physical abuse. In this case, race trumped religion: Muslim Greeks were forced west, and Christian Turks forced east, and the population exchange destroyed a vital, multicultural ethnic patchwork. The agreements at Lausanne became a model for future examples of ethnic cleansing, most notably the exchange of Germans and Slavs in central Europe after the Second World War, and the exchange of Hindus and Muslims that followed Indian independence in 1947.

Kemal, a nationalist without religious faith, believed that Turkey should modernize and secularize along Western lines. He established a republic, was elected president, and created a one-party system — partly inspired by the Bolshevik example — to transform his country. The most radical reforms pertained to religion and culture. For centuries, Islamic religious authorities had regulated most of the intellectual, political, and social activities of Ottoman citizens. Profoundly influenced by the example of western Europe, Kemal set out to limit the place of religion and religious leaders in daily affairs. He decreed a controversial separation of church and state, promulgated law codes inspired by European models, and established a secular public school system. Women received rights that they never had before. By the time of his death in 1938, Kemal had implemented much of his revolutionary program and had moved Turkey much closer to Europe, foretelling current efforts by Turkey to join the European Union as a full-fledged member.