Thinking Like a Historian: Violence and the Algerian War

970

Violence and the Algerian War

In the course of the eight-

| 1 |

An argument for revolutionary violence. While thinkers like Frantz Fanon called for anti- |

![]() It is necessary to turn political crisis into armed conflict by performing violent actions that will force those in power to transform the political situation of the country into a military situation. That will alienate the masses, who, from then on, will revolt against the army and the police and blame them for the state of things.

It is necessary to turn political crisis into armed conflict by performing violent actions that will force those in power to transform the political situation of the country into a military situation. That will alienate the masses, who, from then on, will revolt against the army and the police and blame them for the state of things.

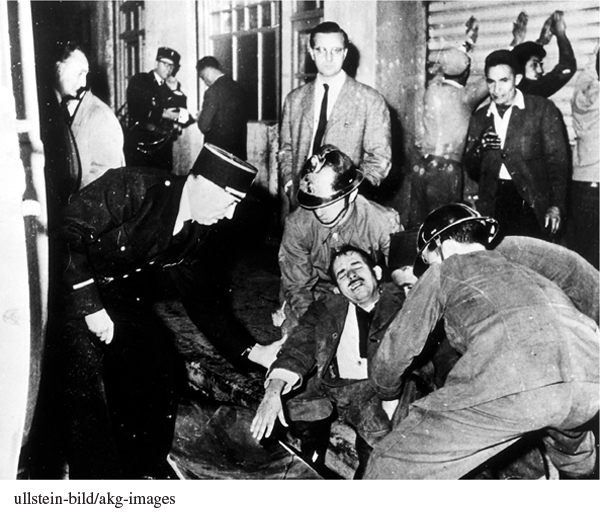

| 2 | An argument for torture. French soldiers and police routinely tortured FLN members and other Algerians suspected of supporting the insurgents in order to gain information and intimidate the general population. Colonel Antoine Argoud, a commander of a French paratroop force sent to Algeria, argued for the necessity of torture. |

![]() Muslims will not talk as long . . . as long as we do not inflict acts of violence on them. . . .

Muslims will not talk as long . . . as long as we do not inflict acts of violence on them. . . .

Torture is an act of violence just like the bullet shot from a gun, the [cannon] shell, the flame-

It is my choice. I will carry out public executions, I’ll shoot those absolutely guilty. Justice will therefore be just. It will conform to the first criterion of Christian justice. I’ll expose their corpses to the public . . . not out of some sadist feeling, but to enhance the virtue of exemplary justice. . . .

To the great astonishment of my men, I then decided to bring the corpses [of presumed insurgents killed in an air strike] back to M’sila to expose them to the population. . . .

| 3 |

The Philippeville massacres, August 20, 1955. Faced by setbacks, the FLN decided to mount an open attack on the coastal region of Philippeville. A violent group, encouraged by FLN insurgents, massacred 123 European settlers. Enraged by the atrocities — the mob had brutally assaulted elderly men, women, and children — French army units, police, and settler vigilantes retaliated by killing at least 1,273 insurgents and Muslim- |

![]() [The bodies of French colonial settlers] literally strewed the town. The Arab children, wild with enthusiasm — to them it was a great holiday — rushed about yelling among the grown-

[The bodies of French colonial settlers] literally strewed the town. The Arab children, wild with enthusiasm — to them it was a great holiday — rushed about yelling among the grown-

971

[Catching up with a group of “rebels,” mingled with civilians,] we opened fire into the thick of them, at random. Then as we moved on and found more bodies, our company commanders finally gave us the order to shoot down every Arab we met. You should have seen the result. . . .

At midday, fresh orders: take prisoners. That complicated everything. It was easy when it was merely a matter of killing. . . .

| 4 |

A 1956 FLN terror bombing in Algiers. The violence continued to escalate after the Philippeville massacres, and in 1956 the FLN formally embraced terrorism, expanding its attacks on the colonial state to include European civilians. This FLN bomb attack, intended to strike a French police patrol in a working- |

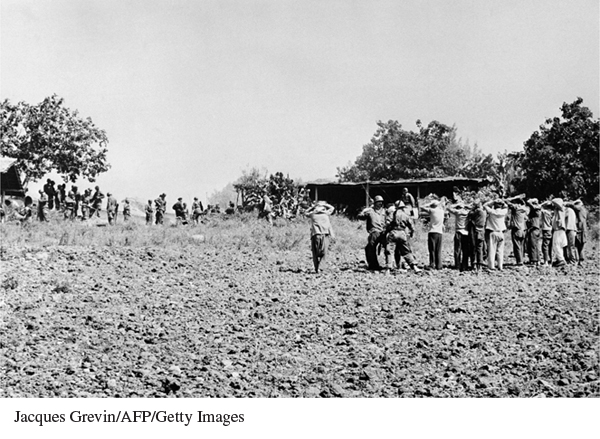

| 5 | Pacification of the Algerian countryside. Fighting took place in the capital of Algiers and other cities, but the Algerian War was largely fought in the countryside. In attempts to “pacify” the Algerian peasantry, French forces undertook numerous campaigns in rural areas like the one pictured here. Soldiers checked identity cards, searched for weapons, arrested villagers and moved them to internment centers, and at times tortured and summarily executed those they suspected of supporting the FLN. |

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

- What are the main arguments made for the use of violence and terror in Sources 1 and 2, and in the Frantz Fanon selection (see “Evaluating the Evidence 28.3: Frantz Fanon on Violence, Decolonization, and Human Dignity)? Are any of these arguments legitimate?

- Review the firsthand accounts by French soldiers who fought against FLN insurgents (Sources 2 and 3). What is their attitude toward Algerian Muslims?

- Consider Sources 2–5. Did the use of violence and terror have unintended consequences?

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

War inevitably involves the use of deadly, unrestrained violence, but historians agree that the Algerian War was particularly brutal. Using the sources above, along with what you have learned in class and in this chapter, write a short essay that explores the use of violence in the process of decolonization. Why was violence so central — and so savage — in the Algerian struggle for independence?

Sources: (1) Alejandro Colás and Richard Saull, eds., The War on Terrorism and the American “Empire” After the Cold War (New York: Routledge, 2007), p. 190; (2) Marnia Lazreg, Torture and the Twilight of Empire: From Algiers to Baghdad (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2008), pp. 89–92; (3) Alistair Horne, A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954–1962 (New York: Viking, 1978), p. 121.