Thinking Like a Historian: Gender Roles in Classical Athens

84

Gender Roles in Classical Athens

Athenian men’s ideas about the proper roles for men and women, conveyed in written and visual form, became a foundation of Western notions of gender. How do the qualities they view as ideal and praiseworthy for men compare with those they view as ideal for women?

| 1 | Pericles’s funeral oration, from Thucydides’s History of the Peloponnesian War, 430 B.C.E. In this speech given in honor of those who had died in the war, the Athenian leader Pericles glorifies the achievements of Athenian men and women. |

![]() If we look to the laws, they afford equal justice to all in their private differences; if to social standing, advancement in public life falls to reputation for capacity, class considerations not being allowed to interfere with merit; nor again does poverty bar the way, if a man is able to serve the state, he is not hindered by the obscurity of his condition. . . .

If we look to the laws, they afford equal justice to all in their private differences; if to social standing, advancement in public life falls to reputation for capacity, class considerations not being allowed to interfere with merit; nor again does poverty bar the way, if a man is able to serve the state, he is not hindered by the obscurity of his condition. . . .

If I must say anything on the subject of female excellence to those of you who will now be in widowhood, it will be all comprised in this brief exhortation: Great will be your glory in not falling short of your natural character; and greatest will be hers who is least talked of among the men whether for good or for bad.

| 2 | Xenophon, Oeconomicus, ca. 360 B.C.E. In a treatise on household management, the historian, soldier, and philosopher Xenophon creates a character, Isomachus, who provides his much younger wife with advice and informs her about ideal gender roles. “God” in this selection means all of the gods, personified as male; “law” is personified as female (“law gives her consent”). |

![]() ISOMACHUS: “God made provision from the first by shaping, as it seems to me, the woman’s nature for indoor and the man’s for outdoor occupations. Man’s body and soul He furnished with a greater capacity for enduring heat and cold, wayfaring and military marches; or, to repeat, He laid upon his shoulders the outdoor works. While in creating the body of woman with less capacity for these things,” I continued, “God would seem to have imposed on her the indoor works; and knowing that He had implanted in the woman and imposed upon her the nurture of new-

ISOMACHUS: “God made provision from the first by shaping, as it seems to me, the woman’s nature for indoor and the man’s for outdoor occupations. Man’s body and soul He furnished with a greater capacity for enduring heat and cold, wayfaring and military marches; or, to repeat, He laid upon his shoulders the outdoor works. While in creating the body of woman with less capacity for these things,” I continued, “God would seem to have imposed on her the indoor works; and knowing that He had implanted in the woman and imposed upon her the nurture of new-

85

| 3 | Aristotle, The Politics. In The Politics, one of his most important works, Aristotle examines the development of government, which he sees as originating in the power relations in the family and household. |

![]() The city belongs among the things that exist by nature, and man is by nature a political animal. . . .

The city belongs among the things that exist by nature, and man is by nature a political animal. . . .

It is clear that the rule of the soul over the body, and of the mind and the rational element over the passionate, is natural and expedient; whereas the equality of the two or the rule of the inferior is always hurtful. The same holds good of animals in relation to men; for tame animals have a better nature than wild, and all tame animals are better off when they are ruled by man; for then they are preserved. Again, the male is by nature superior, and the female inferior; and the one rules, and the other is ruled; this principle, of necessity, extends to all mankind. . . .

A similar question may be raised about women and children, whether they too have virtues: ought a woman to be temperate and brave and just, and is a child to be called temperate, and intemperate, or not? . . . Here the very constitution of the soul has shown us the way; in it one part naturally rules, and the other is subject, and the virtue of the ruler we maintain to be different from that of the subject; the one being the virtue of the rational, and the other of the irrational part. Now, it is obvious that the same principle applies generally, and therefore almost all things rule and are ruled according to nature. . . .

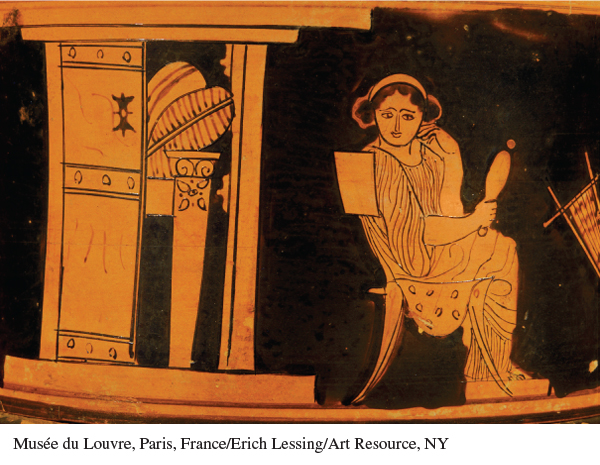

| 4 |

Vase painting showing Athenian woman at home, fifth century B.C.E. A well- |

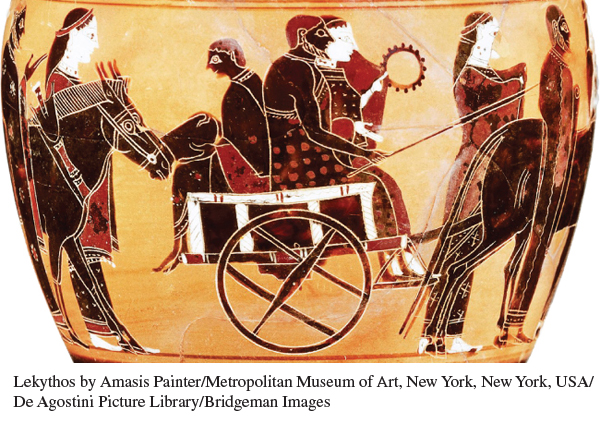

| 5 | Lekythos (oil flask), with a wedding scene, attributed to the Amasis Painter, ca. 550 B.C.E. In this early representation of an Attic wedding procession, the bearded groom drives the cart to his home, while the bride (right) pulls her veil forward in a gesture associated with marriage in Greek art. |

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

- In Sources 1–3, what qualities do the authors see as praiseworthy in men? In women?

- In Sources 2 and 3, what do Xenophon and Aristotle view as the underlying reasons for gender differences?

- The two paintings in Sources 4 and 5 show scenes that were normal parts of real Athenian life, but how do they also convey ideals for men and women? What are these ideals?

- Because no writing or art by Athenian women has survived, we have to extrapolate women’s opinions from works by men. What does the body language and expression of the young woman in Source 4 suggest she thought about her situation?

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Using the sources above, along with what you have learned in class and in Chapter 3, write a short essay that compares ideals for men and women in classical Athens. How did these ideas about gender roles both reflect and shape Athenian society and political life?

Sources: (1) Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War (London: J. M. Dent; New York, E. P. Dutton, 1910), at Perseus Digital Library; (2) Xenophon, The Economist, trans. H. G. Dakyns, at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1173/1173-