Popular Entertainment

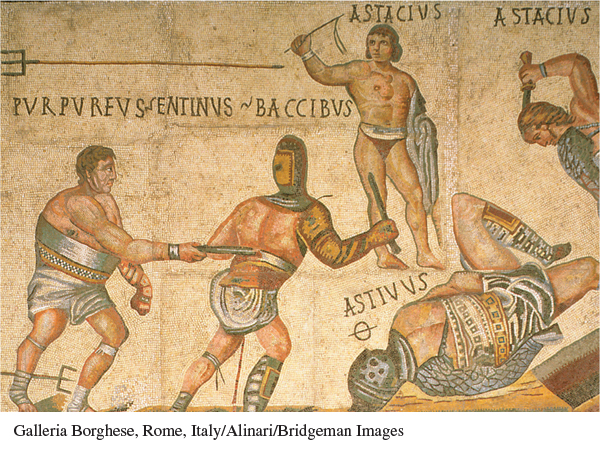

In addition to supplying grain, the emperor and other wealthy citizens also entertained the Roman populace, often at vast expense. This combination of material support and popular entertainment to keep the masses happy is often termed “bread and circuses.” The most popular forms of public entertainment were gladiatorial contests and chariot racing. Gladiatorial combat had begun as a private event during the republic, sponsored by men seeking new ways to honor their ancestors. By the early empire it had grown into a major public spectacle, with sponsors sometimes offering hundreds of gladiator fights along with battles between animals or between animals and humans. Games were advertised on billboards, and spectators were given a program with the names and sometimes the fighting statistics of the pairs, so that they could place bets more easily.

Men came to be gladiators through a variety of ways. Many were soldiers captured in war, sent to Rome or other large cities to be gladiators instead of being killed. Some were criminals, especially slaves found guilty of various crimes. By the imperial period increasing numbers were volunteers, often poor immigrants who saw gladiatorial combat as a way to support themselves. All gladiators were trained in gladiatorial schools and were legally slaves, although they could keep their winnings and a few became quite wealthy. The Hollywood portrayal of gladiatorial combat has men fighting to their death, but this was increasingly rare, as the owners of especially skilled fighters wanted them to continue to compete. Many — perhaps most — did die at a young age from their injuries or later infections, but some fought more than a hundred battles over long careers, retiring to become trainers in gladiatorial schools. Sponsors of matches sought to offer viewers ever more unusual spectacles: left-

The Romans were even more addicted to chariot racing than to gladiatorial shows. Under the empire four permanent teams competed against one another. Each had its own color — red, white, green, or blue. Two-

171

Roman spectacles such as gladiator fights and chariot racing are fascinating subjects for movies and computer games, but they were not everyday activities for Romans. As is evident on tombstone inscriptions, ordinary Romans were proud of their work and accomplishments and affectionate toward their families and friends. An impression of them can be gained from their epitaphs. (See “Living in the Past: Roman Epitaphs: Death Remembers Life.”)