Christianity and Classical Culture

The growth of Christianity was not simply a matter of institutions such as the papacy and monasteries, but also a matter of ideas. The earliest Christian thinkers sometimes rejected Greco-Roman culture, but as Christianity grew from a tiny persecuted group to the official religion of the Roman Empire, its leaders and thinkers gradually came to terms with classical culture (see Chapter 6). They incorporated elements of Greek and Roman philosophy and learning into Christian teachings, modifying them to fit with Christian notions.

Saint Jerome (340–419), for example, a distinguished theologian and linguist regarded as a father of the church, translated the Old and New Testaments from Hebrew and Greek into vernacular Latin. Called the Vulgate, his edition of the Bible served as the official translation until the sixteenth century, and scholars rely on it even today. Familiar with the writings of classical authors, Saint Jerome believed that Christians should study the best of ancient thought because it would direct their minds to God. He maintained that the best ancient literature should be interpreted in light of the Christian faith.

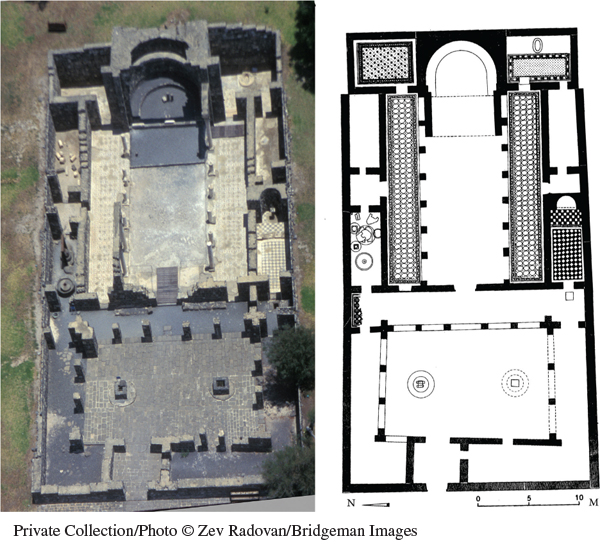

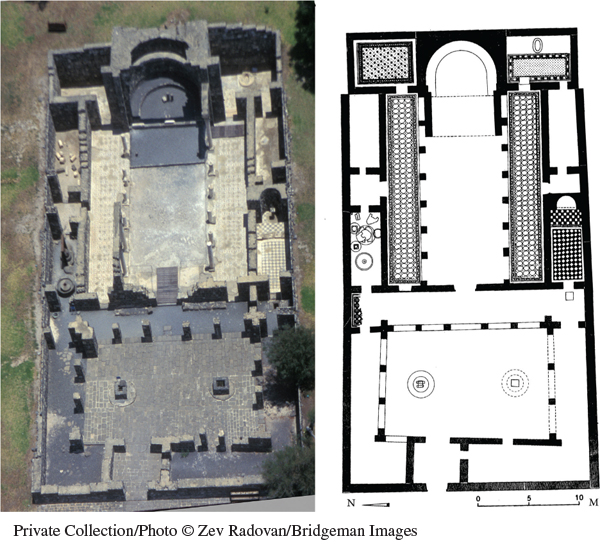

Floor Plan and Foundation of Kursi Monastery Church Built on the eastern shore of the Sea of Galilee in the fifth century at a major pilgrimage site, this walled monastery had living quarters for the monks, a guesthouse, and a bath for pilgrims. It contained a church modeled on the type of Roman public building known as a basilica, with an open courtyard with two wells (near the bottom in the pictures), mosaic floors, and a central nave separated from side aisles by rows of arched columns. In one side chapel (on the left in the pictures) was a small baptismal font, and in another a press for olive oil, a major source of income for the monastery. The skeletons of thirty monks were found in a crypt when the site was uncovered during road construction in 1970.

(Private Collection/Photo © Zev Radovan/Bridgeman Images)