Thinking Like a Historian: Christian and Muslim Views of the Crusades

Christian and Muslim Views of the Crusades

Both Christians and Muslims wrote accounts of the Crusades as they happened, which circulated among those who could read and served as the basis for later histories and visual depictions. How do Christian and Muslim views differ, and how are they similar?

| 1 |

Peter Tudebode on the fall of Antioch, 1098. Peter Tudebode was a French priest who accompanied the First Crusade and later wrote an account of it. |

There was a Turkish emir [high-ranking army officer], Firuz, who became very friendly with Bohemond [a Norman noble, one of the leaders of the First Crusade]. Often through mutual messengers Bohemond suggested that Firuz admit him to Antioch; and, in turn, the Norman offered him the Christian religion along with great wealth from many possessions. Firuz, in accepting these provisions, replied: “I pledge freely the delivery of three towers of which I am a custodian.”. . . The knights took to the plain and the footmen to the mountain, and all night they maneuvered and marched until almost daybreak, when they came to the towers which Firuz guarded. Bohemond immediately dismounted and addressed the group: “Go in dare-devil spirit and great elan, and mount the ladder into Antioch, which shall soon be in our hands if God so wills.” They then went to a ladder, which was raised and lashed to the walls of the city, and almost sixty of our men scaled the ladder and divided their forces in the towers guarded by Firuz. . . . [W]e crashed down the gate, and poured into Antioch. . . . At sunup the crusaders who were outside Antioch in their tents, upon hearing piercing shrieks arising from the city, raced out and saw the banner of Bohemond flying high on the hill. Thereupon they rushed forth and each one speedily came to his assigned gate and entered Antioch, killing Turks and Saracens whom they found. . . . Yaghi Siyan, commander of Antioch, in great fear of the Franks, took to heel along with many of his retainers. . . . All of the streets of Antioch were choked with corpses so that the stench of rotting bodies was unendurable, and no one could walk the streets without tripping over a cadaver.

There was a Turkish emir [high-ranking army officer], Firuz, who became very friendly with Bohemond [a Norman noble, one of the leaders of the First Crusade]. Often through mutual messengers Bohemond suggested that Firuz admit him to Antioch; and, in turn, the Norman offered him the Christian religion along with great wealth from many possessions. Firuz, in accepting these provisions, replied: “I pledge freely the delivery of three towers of which I am a custodian.”. . . The knights took to the plain and the footmen to the mountain, and all night they maneuvered and marched until almost daybreak, when they came to the towers which Firuz guarded. Bohemond immediately dismounted and addressed the group: “Go in dare-devil spirit and great elan, and mount the ladder into Antioch, which shall soon be in our hands if God so wills.” They then went to a ladder, which was raised and lashed to the walls of the city, and almost sixty of our men scaled the ladder and divided their forces in the towers guarded by Firuz. . . . [W]e crashed down the gate, and poured into Antioch. . . . At sunup the crusaders who were outside Antioch in their tents, upon hearing piercing shrieks arising from the city, raced out and saw the banner of Bohemond flying high on the hill. Thereupon they rushed forth and each one speedily came to his assigned gate and entered Antioch, killing Turks and Saracens whom they found. . . . Yaghi Siyan, commander of Antioch, in great fear of the Franks, took to heel along with many of his retainers. . . . All of the streets of Antioch were choked with corpses so that the stench of rotting bodies was unendurable, and no one could walk the streets without tripping over a cadaver.

| 2 |

Ibn al-Athir on the fall of Antioch. Ali Ibn al-Athir (1160–1223), a Kurdish scholar and historian who lived in Mosul (today’s Iraq), wrote a history of the First Crusade that relied on Arab sources. |

Yaghi Siyan, the ruler of Antioch, showed unparalleled courage and wisdom, strength and judgment. If all the Franks who died had survived they would have overrun all the lands of Islam. He protected the families of the Christians in Antioch and would not allow a hair of their heads to be touched. After the siege had been going on for a long time the Franks made a deal with . . . an armor-maker called Ruzbih whom they bribed with a fortune in money and lands. He worked in the tower that stood over the riverbed, where the river flowed out of the city into the valley. The Franks sealed their pact with the armor-maker, God damn him! and made their way to the watergate. They opened it and entered the city. Another gang of them climbed the tower with their ropes. At dawn, when more than 500 of them were in the city and the defenders were worn out after the night watch, they sounded their trumpets. . . . Panic seized Yaghi Siyan and he opened the city gates and fled in terror, with an escort of thirty pages. . . . This was of great help to the Franks, [who] entered the city by the gates and sacked it, slaughtering all the Muslims they found there. . . .

Yaghi Siyan, the ruler of Antioch, showed unparalleled courage and wisdom, strength and judgment. If all the Franks who died had survived they would have overrun all the lands of Islam. He protected the families of the Christians in Antioch and would not allow a hair of their heads to be touched. After the siege had been going on for a long time the Franks made a deal with . . . an armor-maker called Ruzbih whom they bribed with a fortune in money and lands. He worked in the tower that stood over the riverbed, where the river flowed out of the city into the valley. The Franks sealed their pact with the armor-maker, God damn him! and made their way to the watergate. They opened it and entered the city. Another gang of them climbed the tower with their ropes. At dawn, when more than 500 of them were in the city and the defenders were worn out after the night watch, they sounded their trumpets. . . . Panic seized Yaghi Siyan and he opened the city gates and fled in terror, with an escort of thirty pages. . . . This was of great help to the Franks, [who] entered the city by the gates and sacked it, slaughtering all the Muslims they found there. . . .

It was the discord between the Muslim princes . . . that enabled the Franks to overrun the country.

| 3 |

Fulcher of Chartres on the fall of Jerusalem to the Crusaders, 1099. Fulcher was a chaplain to military leaders on the First Crusade and over several decades wrote a long and influential chronicle. |

Soon thereafter the Franks gloriously entered the city at noon on the day known as Dies Veneris, the day in which Christ redeemed the whole world on the Cross. [That is, a Friday.] Amid the sound of trumpets and with everything in an uproar they attacked boldly, shouting “God help us!” At once they raised a banner in the city on the top of the wall. . . . They ran with the greatest exultation as fast as they could into the city and joined their companions in pursuing and slaying their wicked enemies without cessation. . . . If you had been there your feet would have been stained to the ankles in the blood of the slain. What shall I say? None of them were left alive. Neither women nor children were spared. How astonishing it would have seemed to you to see our squires and footmen, after they discovered the trickery of the Saracens, split open the bellies of those they had just slain in order to extract from the intestines the bezants [gold coins minted in Byzantium] which the Saracens had gulped down their loathsome throats while still alive! . . . After this great slaughter they entered the houses of the citizens, seizing whatever they found in them. This was done in such a way that whoever first entered a house, whether he was rich or poor, was not challenged by any other Frank. In this way many poor people became wealthy.

Soon thereafter the Franks gloriously entered the city at noon on the day known as Dies Veneris, the day in which Christ redeemed the whole world on the Cross. [That is, a Friday.] Amid the sound of trumpets and with everything in an uproar they attacked boldly, shouting “God help us!” At once they raised a banner in the city on the top of the wall. . . . They ran with the greatest exultation as fast as they could into the city and joined their companions in pursuing and slaying their wicked enemies without cessation. . . . If you had been there your feet would have been stained to the ankles in the blood of the slain. What shall I say? None of them were left alive. Neither women nor children were spared. How astonishing it would have seemed to you to see our squires and footmen, after they discovered the trickery of the Saracens, split open the bellies of those they had just slain in order to extract from the intestines the bezants [gold coins minted in Byzantium] which the Saracens had gulped down their loathsome throats while still alive! . . . After this great slaughter they entered the houses of the citizens, seizing whatever they found in them. This was done in such a way that whoever first entered a house, whether he was rich or poor, was not challenged by any other Frank. In this way many poor people became wealthy.

| 4 |

Al-Isfahani on Saladin’s retaking of Jerusalem, 1187. Imad ad-Din al-Isfahani (1125–1187) was a Persian scholar who served as secretary to Saladin and accompanied him on many of his military campaigns. |

Saladin marched forward to take the reins of Jerusalem. . . . [T]he Franks despaired of finding any relief from their situation and decided all to give their lives (in defense of Jerusalem). . . . The Sultan mounted catapults, and by this means milked the udders of slaughter. . . . [I]n every heart on either side burned the fire of longing, faces were exposed to the blade’s kiss, hearts were tormented with longing for combat. . . . Every onslaught was energetic and achieved its object, the goal was reached, the enemy wounded. . . . The city became Muslim and the infidel belt around it was cut. . . . By striking coincidence the date of the conquest of Jerusalem was the anniversary of the Prophet’s ascension to heaven. Great joy reigned for the brilliant victory won, and words of prayer and invocation to God were on every tongue. . . . Ibn Barzun [Balian of Ibelin, one of the Crusader leaders] came out to secure a treaty with the Sultan, and asked for an amnesty for his people. . . . [A]n amount was fixed for which they were to ransom themselves and their possessions . . . ten dinar for every man, five for a woman, and two for a boy or girl. . . . Every man who paid left his house in safety, and the rest were to be enslaved. . . . The Franks began selling their possessions and taking their precious things out of safe-keeping. . . . They scavenged in their own churches and stripped them of their ornaments of gold and silver. . . . Then I said to the Sultan, “These are things of great riches; do not allow these rascals to keep this in their grasp.” But he replied, “If we interpret the treaty to their disadvantage they will accuse us of breaking faith.” So they carried away the most precious and lightest [objects] and shook from their hands the dust of their heritage.

Saladin marched forward to take the reins of Jerusalem. . . . [T]he Franks despaired of finding any relief from their situation and decided all to give their lives (in defense of Jerusalem). . . . The Sultan mounted catapults, and by this means milked the udders of slaughter. . . . [I]n every heart on either side burned the fire of longing, faces were exposed to the blade’s kiss, hearts were tormented with longing for combat. . . . Every onslaught was energetic and achieved its object, the goal was reached, the enemy wounded. . . . The city became Muslim and the infidel belt around it was cut. . . . By striking coincidence the date of the conquest of Jerusalem was the anniversary of the Prophet’s ascension to heaven. Great joy reigned for the brilliant victory won, and words of prayer and invocation to God were on every tongue. . . . Ibn Barzun [Balian of Ibelin, one of the Crusader leaders] came out to secure a treaty with the Sultan, and asked for an amnesty for his people. . . . [A]n amount was fixed for which they were to ransom themselves and their possessions . . . ten dinar for every man, five for a woman, and two for a boy or girl. . . . Every man who paid left his house in safety, and the rest were to be enslaved. . . . The Franks began selling their possessions and taking their precious things out of safe-keeping. . . . They scavenged in their own churches and stripped them of their ornaments of gold and silver. . . . Then I said to the Sultan, “These are things of great riches; do not allow these rascals to keep this in their grasp.” But he replied, “If we interpret the treaty to their disadvantage they will accuse us of breaking faith.” So they carried away the most precious and lightest [objects] and shook from their hands the dust of their heritage.

| 5 |

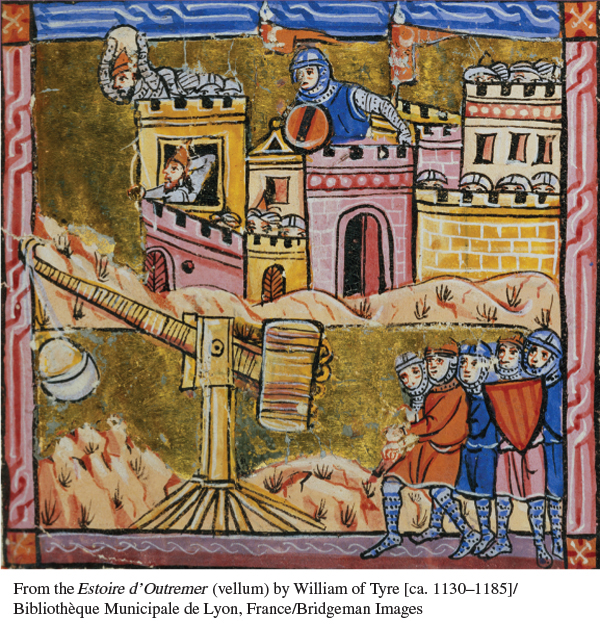

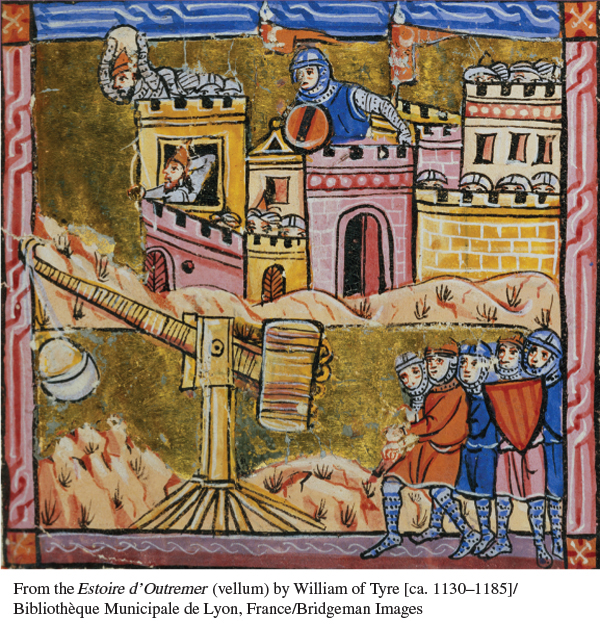

Capture of Antioch. This illustration comes from a 1280 version of William of Tyre’s A History of Deeds Beyond the Sea, the most widely read account of the Crusades, which drew extensively on earlier histories. |

(From the Estoire d’Outremer (vellum) by William of Tyre [ca. 1130–1185]/Bibliothèque Municipale de Lyon, France/Bridgeman Images)

- How do Sources 1 and 2 differ in how they portray Yaghi Siyan and the man who opened the towers of Antioch to Christian forces? How do these and other differences influence the story?

- In Sources 3 and 4, how is the course of the two battles for Jerusalem different? How is the aftermath different?

- How does the artist who painted Source 5 convey his ideas about why the battle ended as it did?

- How do these accounts balance the various aims—religious devotion, military glory, economic gain—of the two sides?

Using the sources above, along with what you have learned in class and in this chapter, write a short essay that analyzes Christian and Muslim views of the Crusades. How did they differ, and how were they similar? How did the Crusades help shape the understanding that Christians and Muslims had of each other?

Sources: (1) Peter Tudebode, Historia de Hierosolymitano Itinere, trans. and ed. John H. Hill and Laurita L. Hill (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1974), pp. 56–57; (2) Francesco Gabrieli, trans. and ed., Arab Historians of the Crusades, pp. 3–5. Translation © 1969 by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. Published by the University of California Press. Used by permission of the University of California Press and by permission of Taylor & Francis Books UK; (3) Fulcher of Chartres, A History of the Expedition to Jerusalem, 1095–1127, trans. Frances Rita Ryan and ed. Harold S. Fink (Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 1969), pp. 121–122; (4) Gabrieli, Arab Historians of the Crusades, pp. 147, 150, 154, 155, 156, 157–158, 162.

![]() There was a Turkish emir [high-

There was a Turkish emir [high-![]() Yaghi Siyan, the ruler of Antioch, showed unparalleled courage and wisdom, strength and judgment. If all the Franks who died had survived they would have overrun all the lands of Islam. He protected the families of the Christians in Antioch and would not allow a hair of their heads to be touched. After the siege had been going on for a long time the Franks made a deal with . . . an armor-

Yaghi Siyan, the ruler of Antioch, showed unparalleled courage and wisdom, strength and judgment. If all the Franks who died had survived they would have overrun all the lands of Islam. He protected the families of the Christians in Antioch and would not allow a hair of their heads to be touched. After the siege had been going on for a long time the Franks made a deal with . . . an armor-![]() Soon thereafter the Franks gloriously entered the city at noon on the day known as Dies Veneris, the day in which Christ redeemed the whole world on the Cross. [That is, a Friday.] Amid the sound of trumpets and with everything in an uproar they attacked boldly, shouting “God help us!” At once they raised a banner in the city on the top of the wall. . . .

Soon thereafter the Franks gloriously entered the city at noon on the day known as Dies Veneris, the day in which Christ redeemed the whole world on the Cross. [That is, a Friday.] Amid the sound of trumpets and with everything in an uproar they attacked boldly, shouting “God help us!” At once they raised a banner in the city on the top of the wall. . . .![]() Saladin marched forward to take the reins of Jerusalem. . . .

Saladin marched forward to take the reins of Jerusalem. . . .