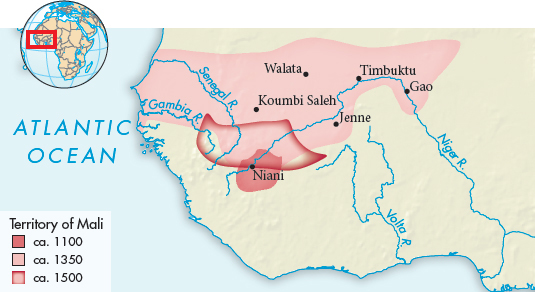

The Kingdom of Mali, ca. 1200–1450

Ghana and its capital of Koumbi Saleh were in decline between 1100 and 1200, and a cloud of obscurity hung over the western Sudan. The old empire split into several small kingdoms that feuded among themselves. One people, the Mandinka, from the kingdom of Kangaba on the upper Niger River, gradually asserted their dominance over these kingdoms. The Mandinka had long been part of the Ghanaian empire, and the Mandinka and Soninke belonged to the same language group. Kangaba formed the core of the new empire of Mali. Building on Ghanaian foundations, Mali developed into a better-

Mali owed its greatness to two fundamental assets. First, its strong agricultural and commercial base supported a large population and provided enormous wealth. Second, Mali had two rulers, Sundiata (soon-

The earliest surviving evidence about the Mandinka, dating from the early eleventh century, indicates that they were extremely successful at agriculture. Consistently large harvests throughout the twelfth and thirteenth centuries meant a plentiful food supply, which encouraged steady population growth. Kangaba’s geographical location also ideally positioned the Mandinka in the heart of the West African trade networks. Earlier, during the period of Ghanaian hegemony, the Mandinka had acted as middlemen in the gold and salt traffic flowing north and south. In the thirteenth century Mandinka traders formed companies, traveled widely, and gradually became a major force in the entire West African trade.

Mali’s founder, Sundiata (r. ca. 1230–

These expansionist policies were continued in the fourteenth century by Sundiata’s descendant Mansa Musa (r. ca. 1312–

Mansa Musa built on the foundations of his predecessors. Malian society’s stratified aristocratic structure perpetuated the pattern set in Ghana, as did the system of provincial administration and annual tribute. The emperor took responsibility for the territories that formed the heart of the empire and appointed governors to rule the outlying provinces and dependent kingdoms. But Mansa Musa made a significant innovation: in a practice strikingly similar to a system used in both China and France at the time, he appointed royal family members as provincial governors. He could count on their loyalty, and they received valuable experience in the work of government.

In another aspect of administration, Mansa Musa also differed from his predecessors. He became a devout Muslim. Although most of the Mandinka clung to their ancestral animism, Islamic practices and influences in Mali multiplied.

The most celebrated event of Mansa Musa’s reign was his pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324–

This man Mansa Musa spread upon Cairo the flood of his generosity: there was no person, officer of the court, or holder of any office of the Sultanate who did not receive a sum of gold from him. The people of Cairo earned incalculable sums from him, whether by buying and selling or by gifts. So much gold was current in Cairo that it ruined the value of money.11

For the first time, the Mediterranean world learned firsthand of Mali’s wealth and power, and the kingdom began to be known as one of the world’s great empires. Mali retained this international reputation into the fifteenth century. Musa’s pilgrimage also had significant consequences within Mali. He gained some understanding of the Mediterranean countries and opened diplomatic relations with the Muslim rulers of Morocco and Egypt. His zeal for the Muslim faith and Islamic culture increased. Musa brought back from Arabia the distinguished architect al-

Timbuktu began as a campsite for desert nomads, but under Mansa Musa it grew into a thriving entrepôt (trading center), attracting merchants and traders from North Africa and all parts of the Mediterranean world. They brought with them cosmopolitan attitudes and ideas. In the fifteenth century Timbuktu developed into a great center for scholarship and learning. Architects, astronomers, poets, lawyers, mathematicians, and theologians flocked there. One hundred fifty schools, for men only, were devoted to Qur’anic studies. The school of Islamic law enjoyed a distinction comparable to the prestige of the Cairo school (see “Education and Intellectual Life” in Chapter 9). The vigorous traffic in books that flourished in Timbuktu made them the most common items of trade. Timbuktu’s tradition and reputation for African scholarship lasted until the eighteenth century.

Moreover, in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries many Arab and North African Muslim intellectuals and traders married native African women. The necessity of living together harmoniously, the traditional awareness of diverse cultures, and Timbuktu’s cosmopolitan atmosphere contributed to a rare degree of racial tolerance and understanding. After visiting the court of Mansa Musa’s successor in 1352–

[T]he Negroes possess some admirable qualities. They are seldom unjust, and have a greater abhorrence of injustice than any other people. Their sultan shows no mercy to anyone who is guilty of the least act of it. There is complete security in their country. Neither traveler nor inhabitant in it has anything to fear from robbers. . . . They do not confiscate the property of any white man who dies in their country, even if it be uncounted wealth. On the contrary, they give it into the charge of some trustworthy person among the whites.12

The third great West African empire, Songhai, succeeded Mali in the fourteenth century. It encompassed the old empires of Ghana and Mali and extended its territory farther north and east to become one of the largest African empires in history (see Map 10.2).