Medicine, the Body, and Chemistry

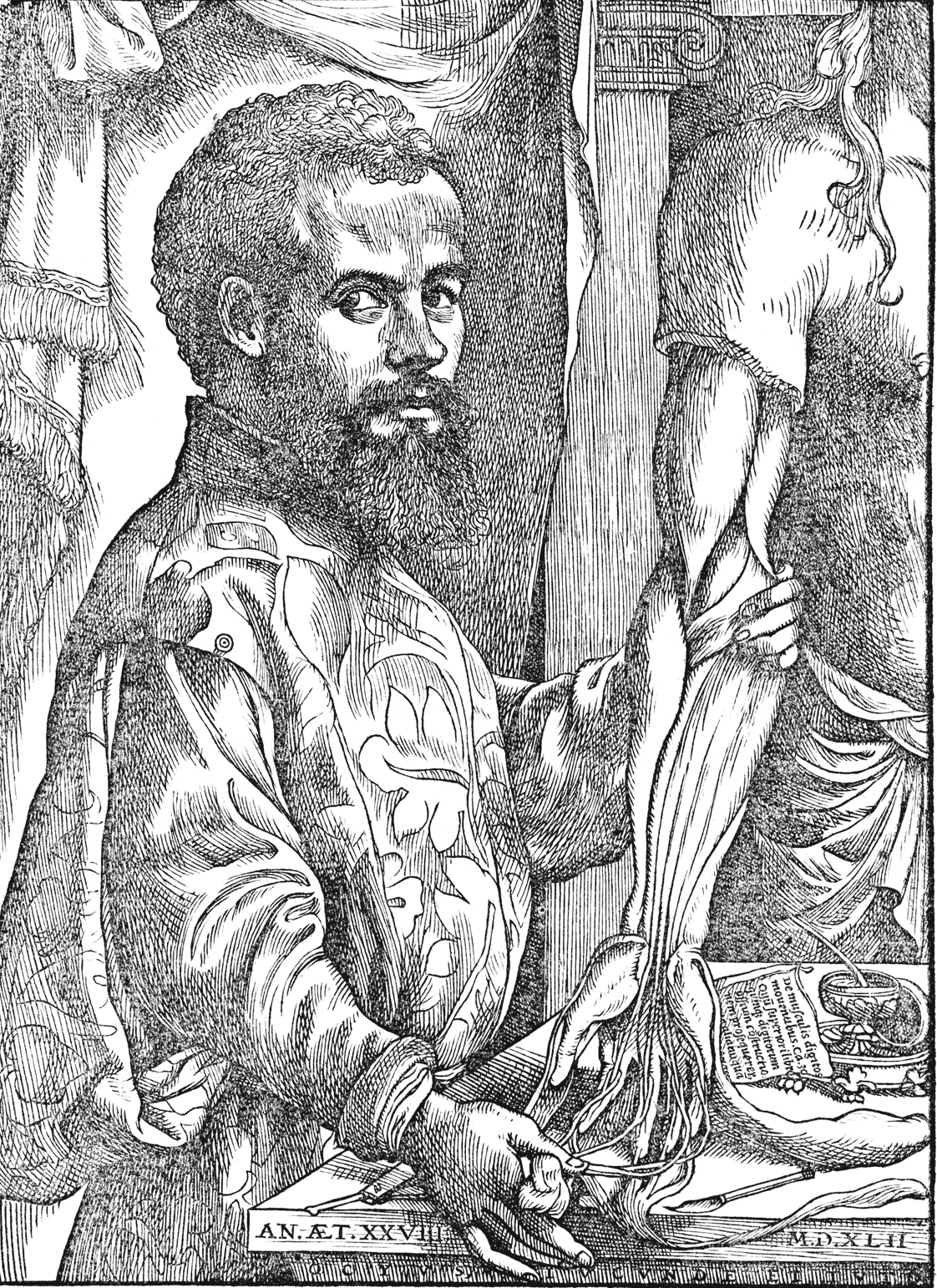

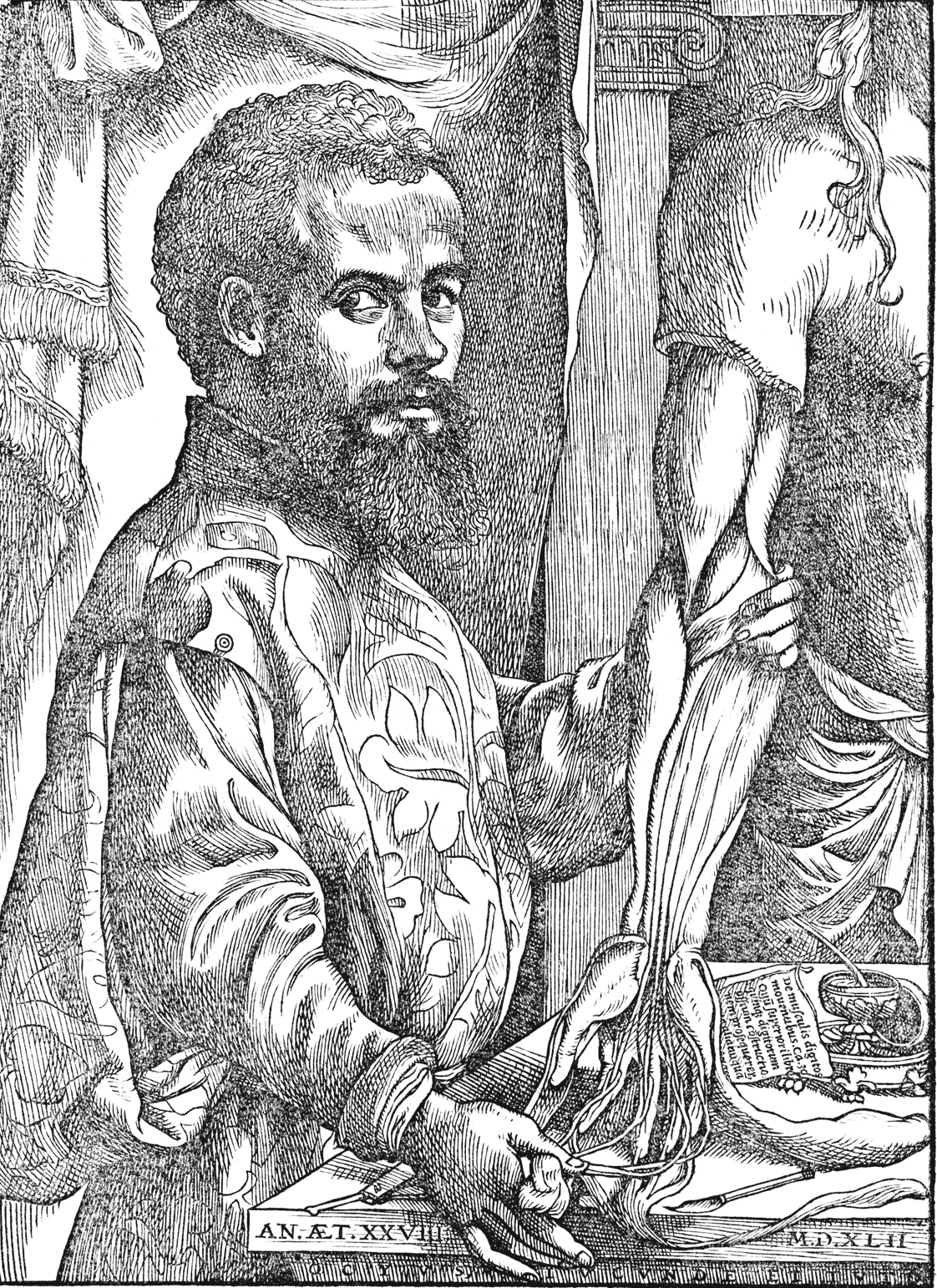

Frontispiece to De Humani Corporis Fabrica (On the Structure of the Human Body) The frontispiece to Vesalius’s pioneering work, published in 1543, shows him dissecting a corpse before a crowd of students. This was a revolutionary new hands-on approach for physicians, who usually worked from a theoretical, rather than a practical, understanding of the body. Based on direct observation, Vesalius replaced ancient ideas drawn from Greek philosophy with a much more accurate account of the structure and function of the body. (© SSPL/Science Museum/The Image Works)

The Scientific Revolution, which began with the study of the cosmos, soon transformed understanding of the microcosm of the human body. For many centuries the ancient Greek physician Galen’s explanation of the body carried the same authority as Aristotle’s account of the universe. According to Galen, the body contained four humors: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. Illness was believed to result from an imbalance of these humors.

Swiss physician and alchemist Paracelsus (1493–1541) was an early proponent of the experimental method in medicine and pioneered the use of chemicals and drugs to address what he saw as chemical, rather than humoral, imbalances. Another experimentalist, Flemish physician Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564), studied anatomy by dissecting human bodies. In 1543, the same year Copernicus published On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, Vesalius issued On the Structure of the Human Body. Its two hundred precise drawings revolutionized the understanding of human anatomy, disproving Galen, just as Copernicus and his successors had disproved Aristotle and Ptolemy. The experimental approach also led English royal physician William Harvey (1578–1657) to discover the circulation of blood through the veins and arteries in 1628. Harvey was the first to explain that the heart worked like a pump and to explain the function of its muscles and valves.

Irishman Robert Boyle (1627–1691) was a key figure in the victory of experimental methods in England and helped create the Royal Society in 1660. Boyle’s scientific work led to the development of modern chemistry. Following Paracelsus’s lead, he undertook experiments to discover the basic elements of nature, which he believed was composed of infinitely small atoms. Boyle was the first to create a vacuum, thus disproving Descartes’s belief that a vacuum could not exist in nature, and he discovered Boyle’s law (1662), which states that the pressure of a gas varies inversely with volume.