Independence from Britain

As fighting spread, the colonists moved slowly toward open calls for independence. The uncompromising attitude of the British government and its use of German mercenaries did much to dissolve loyalties to the home country and to unite the separate colonies. Common Sense (1775), a brilliant attack by the recently arrived English radical Thomas Paine (1737–

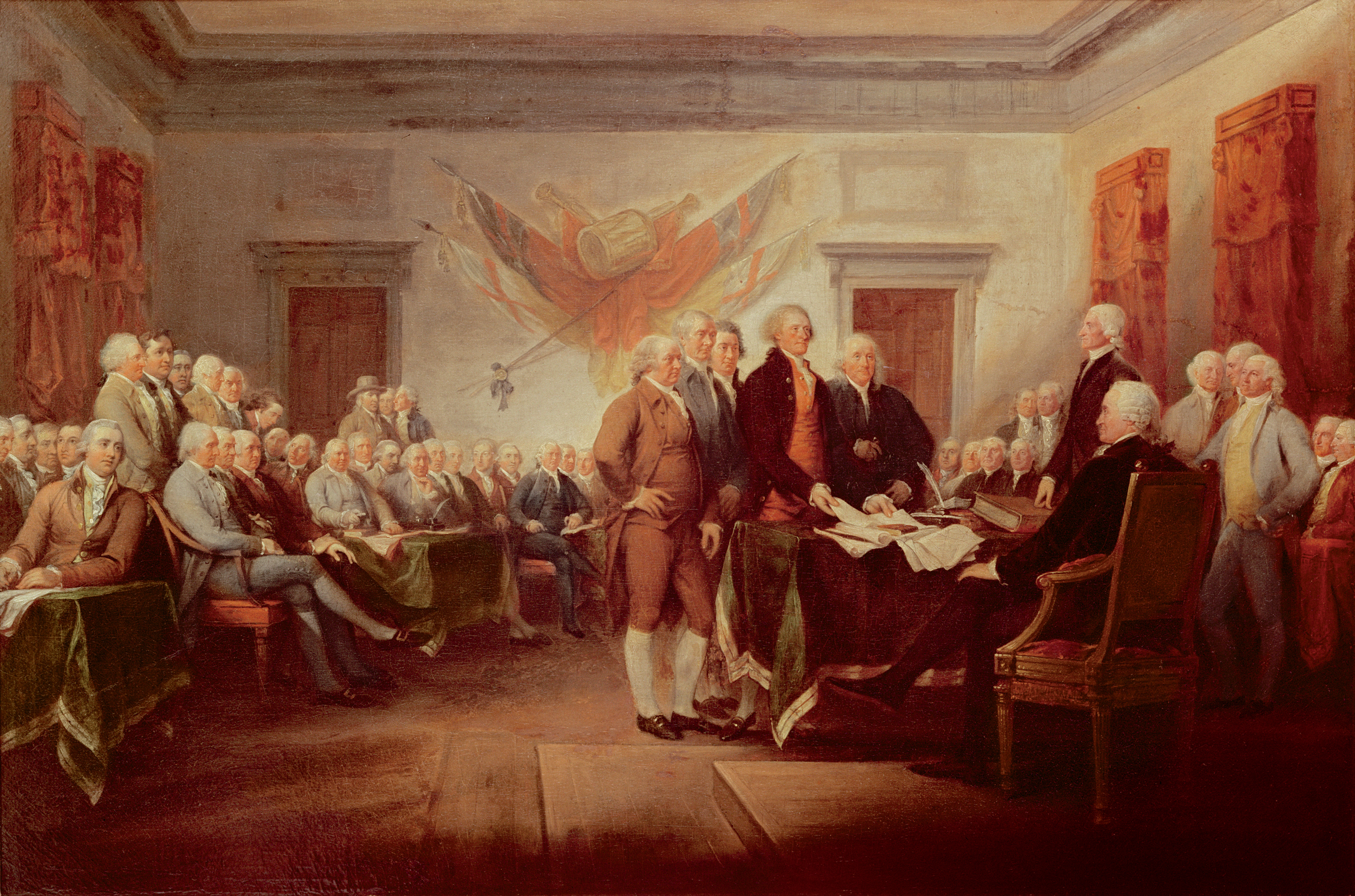

On July 4, 1776, the Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence. Written by Thomas Jefferson and others, this document boldly listed the tyrannical acts committed by George III (r. 1760–

After the Declaration of Independence, the conflict often took the form of a civil war pitting patriots against Loyalists, those who maintained an allegiance to the Crown. The Loyalists, who numbered up to 20 percent of the total white population, tended to be wealthy and politically moderate. They were few in number in New England and Virginia, but more common in the Deep South and on the western frontier. British commanders also recruited Loyalists from enslaved people by promising freedom to any slave who left his master to fight for the mother country.

Many wealthy patriots — such as John Hancock and George Washington — willingly allied themselves with farmers and artisans in a broad coalition. This coalition harassed the Loyalists and confiscated their property to help pay for the war, causing sixty thousand to eighty thousand of them to flee, mostly to Canada. State governments extended the right to vote to many more men, including free African American men in some cases, but not to women.

On the international scene, the French wanted revenge against the British for the humiliating defeats of the Seven Years’ War. Thus they sympathized with the rebels and supplied guns and gunpowder from the beginning of the conflict. By 1777 French volunteers were arriving in Virginia, and a dashing young nobleman, the marquis de Lafayette (1757–

Thus by 1780 Britain was engaged in an imperial war against most of Europe as well as the thirteen colonies. In these circumstances, and in the face of severe reverses in India, in the West Indies, and at Yorktown in Virginia, a new British government decided to cut its losses and end the war. American officials in Paris were receptive to negotiating a deal with England alone, for they feared that France wanted a treaty that would bottle up the new United States east of the Allegheny Mountains and give British holdings west of the Alleghenies to France’s ally, Spain. Thus the American negotiators deserted their French allies and accepted the extraordinarily favorable terms Britain offered.

Under the Treaty of Paris of 1783, Britain recognized the independence of the thirteen colonies and ceded all its territory between the Allegheny Mountains and the Mississippi River to the Americans. Out of the bitter rivalries of the Old World, the Americans snatched dominion over a vast territory.

KEY EVENTS OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION

| 1765 | Britain passes the Stamp Act |

| 1773 | Britain passes the Tea Act |

| 1774 | Britain passes the Coercive Acts in response to the Tea Party in the colonies; the First Continental Congress refuses concessions to the English crown |

| April 1775 | Fighting begins between colonial and British troops |

| July 4, 1776 | The Second Continental Congress adopts the Declaration of Independence |

| 1777– |

The French, Spanish, and Dutch side with the colonists against Britain |

| 1783 | The Treaty of Paris recognizes the independence of the American colonies |

| 1787 | The U.S. Constitution is signed |

| 1791 | The first ten amendments to the Constitution are ratified (the Bill of Rights) |