Science for the Masses

The intellectual achievements of the Scientific Revolution (see Chapter 19) had resulted in few practical benefits, and theoretical knowledge had also played a relatively small role in the Industrial Revolution in England. But breakthroughs in industrial technology stimulated basic scientific inquiry as researchers sought to explain how such things as steam engines and blast furnaces actually worked. The result from the 1830s onward was an explosive growth of fundamental scientific discoveries that were increasingly transformed into material improvements for the general population.

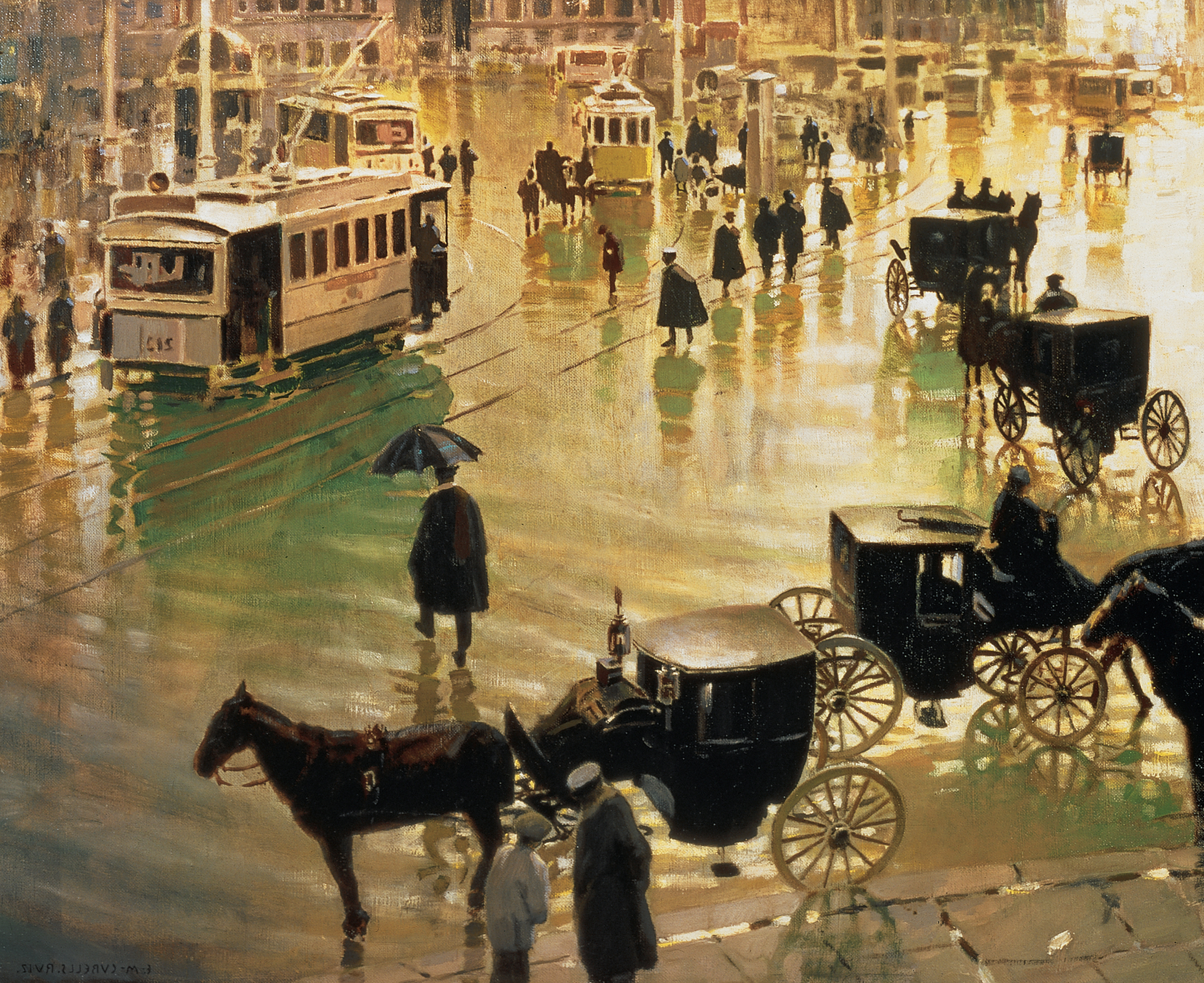

A perfect example of the translation of better scientific knowledge into practical human benefits was the work of Louis Pasteur and his followers in biology and the medical sciences (see “Urban Development”). Another was the development of the branch of physics known as thermodynamics, the study of the relationship between heat and mechanical energy. By midcentury physicists had formulated the fundamental laws of thermodynamics, which were then applied to mechanical engineering, chemical processes, and many other fields. Electricity was transformed from a curiosity in 1800 to a commercial form of energy, first used in communications (the telegraph), then in electrochemistry, and finally in central power generation (for lighting, streetcars, and industrial motors). By 1890 the internal combustion engine fueled by petroleum was an emerging competitor to steam and electricity.

Though ordinary citizens continued to lack detailed scientific knowledge, everyday experience and innumerable articles in newspapers and magazines impressed the importance of science on the popular mind. The methods of science acquired unrivaled prestige after 1850. Many educated people came to believe that the union of careful experiment and abstract theory was the only reliable route to truth and objective reality. The Enlightenment idea that natural processes were determined by rigid laws, leaving little room for either divine intervention or human will, won broad acceptance.

Living in an era of rapid change, nineteenth-

Ever since humans began shaping the world around them tens of thousands of years ago, they have engaged in intentional selection and selective breeding in plants and animals to produce, for example, a new color of rose, a faster racehorse, or chickens that lay more eggs. Natural selection is not intentional; it results when random variations give some individuals an advantage in passing on their genetic material. Combined with the groundbreaking work in genetics carried out by the Augustinian priest and scientist Gregor Johann Mendel (1822–

Darwin’s theory of natural selection provoked resistance, particularly because he extended the theory to humans. His findings reinforced the teachings of secularists such as Marx, who scornfully dismissed religious belief in favor of agnostic or atheistic materialism. Many writers also applied the theory of biological evolution to human affairs. Herbert Spencer (1820–

Not only did science shape society, but society also shaped science. As nations asserted their differences from one another, they sought “scientific” proof for those differences, which generally meant proof of their own superiority. European and American scientists, anthropologists, and physicians measured skulls, brains, and facial angles to prove that whites were more intelligent than other races, and that northern Europeans were more advanced than southern Europeans, perhaps even a separate “Nordic race” or “Aryan race.” Africans were described and depicted as “missing links” between chimpanzees and Europeans, and they were occasionally even displayed as such in zoos and fairs. This scientific racism extended to Jews, who were increasingly described as a separate and inferior race, not a religious group. In the late nineteenth century a German author coined the term “anti-