The World Market

World trade was a powerful stimulus to economic development in the nineteenth century. In 1913 the value of world trade was about twenty-

Great Britain played a key role in using trade to tie the world together economically. In 1815 Britain already possessed a colonial empire, with India, Canada, Australia, and other scattered areas remaining British possessions after American independence. The technological breakthroughs of the Industrial Revolution encouraged British manufacturers to seek export markets around the world. After Parliament repealed laws restricting grain importation in 1846, Britain also became the world’s leading importer of foreign goods. Free access to Britain’s market stimulated the development of mines and plantations in Africa and Asia.

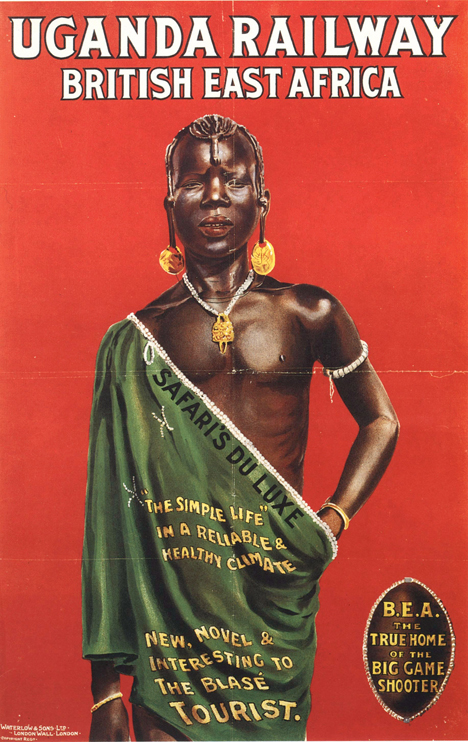

The conquest of distance facilitated the growth of trade. The earliest railroad construction occurred in Europe and in America north of the Rio Grande; railroads were built in other parts of the globe after around 1860. By 1920 about a quarter of the world’s railroads were in Latin America, Asia, Africa, and Australia. Wherever railroads were built, they drastically reduced transportation costs, opened new economic opportunities, and called forth new skills and attitudes.

Much of the railroad construction undertaken in Africa, Asia, and Latin America connected seaports with inland cities and regions, as opposed to linking and developing cities and regions within a country. Thus railroads dovetailed with Western economic interests, facilitating the inflow and sale of Western manufactured goods and the export and development of local raw materials.

Steam power also revolutionized transportation by sea. Long used to drive paddle wheelers on rivers, particularly in Russia and North America, steam power finally began to supplant sails on the world’s oceans in the late 1860s. Lighter, stronger, cheaper steel replaced iron, which had replaced wood. Passenger and freight rates tumbled, and the shipment of low-

The revolution in land and sea transportation helped European settlers seize vast, thinly populated territories and produce agricultural products and raw materials for sale in Europe. Improved transportation enabled Asia, Africa, and Latin America to export not only the traditional tropical products — spices, dyes, tea, sugar, coffee — but also new raw materials for industry, such as jute, rubber, cotton, and peanut and coconut oil. (See “Global Trade: Indigo.”)

Intercontinental trade was enormously facilitated by the Suez Canal and the Panama Canal (see “The Panama Canal” in Chapter 27). Of great importance, too, was large and continual investment in modern port facilities, which made loading and unloading cheaper, faster, and more dependable. Finally, transoceanic telegraph cables inaugurated rapid communications among the world’s financial centers and linked world commodity prices in a global network.

The growth of trade and the conquest of distance encouraged Europeans to make massive foreign investments beginning about 1840, but not in European colonies or protectorates in Asia and Africa. About three-