Global Trade: Indigo

Indigo is the oldest and most important natural colorant, and it serves as an illustrative example of the prodigious growth of world trade in the nineteenth century. Indigo is made from the leaves of a small bush, which are carefully fermented in vats; the extract is then processed into cakes of pigment. It has been highly prized since antiquity because it dyes all fabrics, does not fade with time, and yields tints ranging from light blue to the darkest purple-

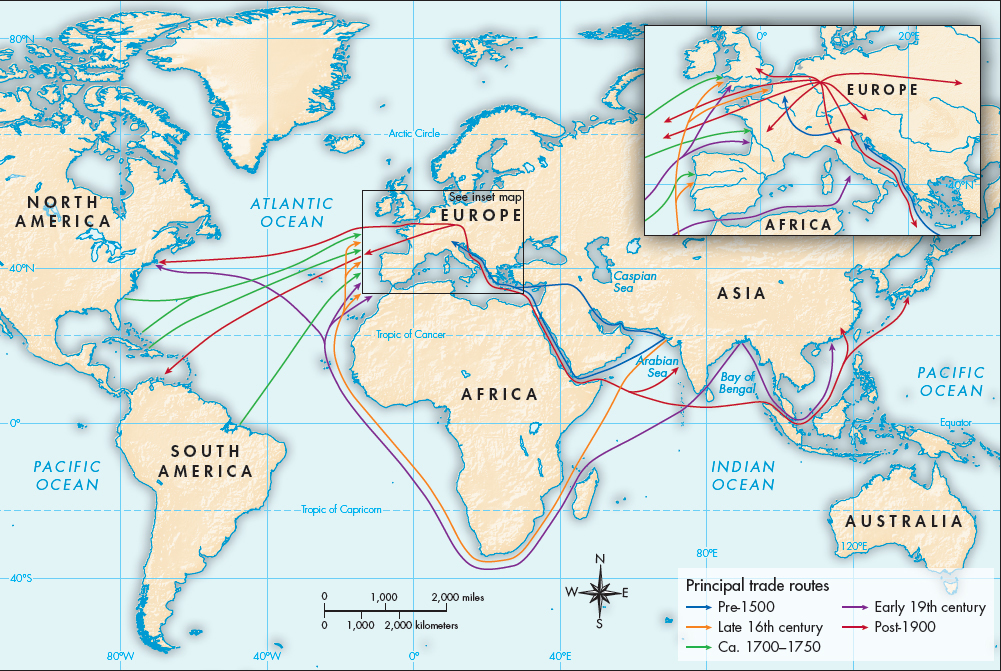

Widely grown and used in Asia, indigo trickled into Europe from western India in the High Middle Ages but was very expensive. Woad — an inferior homegrown product — remained Europe’s main blue dye until the opening of a direct sea route to India by the Portuguese in 1498 reconfigured the intercontinental trade in indigo. Bypassing Muslim traders in the Indian Ocean, first Portuguese and then Dutch and English merchants and trading companies supplied European dyers and consumers with cheaper, more abundant indigo.

In the early seventeenth century indigo became one of the British East India Company’s chief articles of trade, and it was exported from India to Europe more than ever before. As European governments adopted mercantilist policies, they tried to control trade and limit the flow of gold and silver abroad for products like indigo. The result was a second transformation in the global trade in indigo.

Europeans established indigo plantations in their American colonies. By the first half of the eighteenth century very little indigo continued to reach Europe from peasant producers in western India. Indigo plantations in Brazil, Guatemala, Haiti and the Caribbean, and South Carolina were big capitalistic operations and often very profitable. They depended heavily on the work of slaves brought from Africa, as did the entire Atlantic economy at that time.

In the late eighteenth century the geography of the indigo trade shifted dramatically once again: production returned to India, now largely controlled by the British. Why did this happen? Political upheaval in the revolutionary era played a key role. American independence left South Carolina outside Britain’s mercantilist system; the slave rebellion in Haiti in 1791 decimated some of the world’s richest indigo producers; and Britain’s continental blockades cut off Spain and France from their colonies. On the economic side, the takeoff in the British textile industry created surging demand for indigo. Thus in the 1780s the British East India Company hired experienced indigo planters from the West Indies to develop indigo production in Bengal. Leasing lands from Indian zemindars (landlords who doubled as tax collectors), British planters coerced Bengali peasants into growing indigo, which the planters processed in their factories. Business expanded rapidly, as planters made — and lost — fortunes in the boom-

In 1859 Bengali peasants revolted and received unexpected support from British officials advocating free-

Even as the Indigo Disturbances agitated Bengal, industrializing Europe discovered on its doorstep a completely new source of colorants: thick, black coal tar. This residue, a noxious byproduct of the destructive distillation of soft coal for the gas used in urban lighting and heating, was emerging as the basic material for the chemistry of carbon compounds and a new synthetic dye industry. British, German, and French chemists synthesized a small number of dyes between 1856 and 1869, when the first synthetic dye replaced a natural dye. Thereafter, German researchers and Germany’s organic chemical companies built an interlocking global monopoly that produced more than 90 percent of the world’s synthetic dyes.

Indigo was emblematic of this resounding success. Professor Adolf Bayer first synthesized indigo in 1880. But an economically viable process required many years of costly, systematic research before two leading German companies working together achieved their objective in 1897. Producers’ groups in India slashed indigo prices drastically, but to no avail. Indian exports of natural indigo plummeted. Synthetic indigo claimed the global market, German firms earned high profits, and Indian peasants turned to different crops. Today, nearly all the world’s indigo is synthetic, although limited production of natural indigo still occurs in India, as well as in parts of Africa and South America.