Listening to the Past: Reyita Castillo Bueno on Slavery and Freedom in Cuba

Reyita Castillo Bueno was born in Cuba in 1902. When she narrated her life to her granddaughter, she reflected on her own grandmother, an Angolan woman brought to Cuba in the illicit slave trade of the mid-

My Grandma Flew Away

“From my earliest years there are some things I haven’t forgotten, subjects of conversation among the grown-

My grandmother’s name was Antonina, although everyone called her Tatica; she died in 1917. She had beautiful skin, not black-

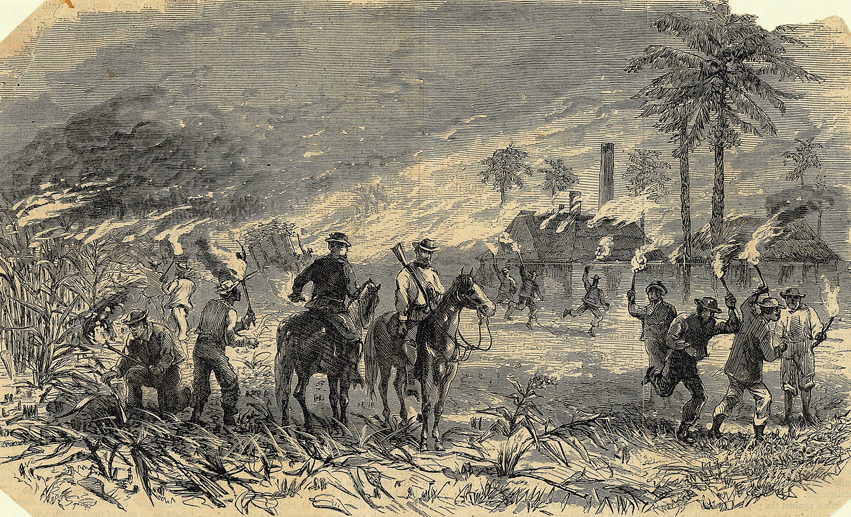

One evening, when the family was at home, having finished working in the fields, and the children were playing, they suddenly heard explosions and shouting. It was a group of white men with guns who were attacking the village, burning the houses and capturing women and men, killing children and old people. It was a terrible massacre. My great-

After such horror came the long march to the steamer — as she used to say — she never managed to figure out how long it lasted. They tied them to each other so they couldn’t escape. . . . On the way they’d be beaten if they fell down from exhaustion or thirst.

The ship that took them from Africa was crammed with men, women and even children, though not many. . . . She said they were the ones the whites couldn’t wrench out of their mothers’ arms. Since it was so full, there was some problem, and although Tatica didn’t know precisely what was wrong, they started throwing men overboard — the oldest, the most frail. What an outrage! Just hearing about it made you want to cry, and even now my eyes well up with tears and you feel tremendously indignant because they threw them overboard alive, with no compassion whatsoever.

When they reached land, Tatica and my aunts didn’t know where they were, it was much later that they found out this was Cuba. They took them to a big hut where they were fed and had water thrown over them. . . . A person from the Hechavarría family bought all three of them. . . . The Hechavarrías also bought other Africans, there were about fifteen or twenty altogether on the plantation. One of them was young and strong and not from my grandmother’s village. His name was Basilio and he and Tatica fell in love.

They lived together secretly so that the masters wouldn’t find out. Although my grandmother didn’t want to have children — and she took preventative infusions of herbs and roots — she got pregnant and had a daughter they named Socorro, who had to work very hard from a very young age. Later my mother was born, she had to work as a slave doing housework for the masters, even though this was after the law of free wombs.

My mother wasn’t Basilio’s daughter, but one of my grandmother’s masters was her father. The slaves couldn’t resist when the masters wanted to take advantage of them. It would have cost them a whipping and the stocks. There was an immoral hypocrisy in those men: on the one hand they looked down on them, but when it came to rape they didn’t care what colour their skin was.

After the abolition of slavery in 1886, Tatica went to live in a little hut which Basilio built on a tiny piece of land he was given. . . . When Basilio joined up with the independence forces in the war of 1895, Tatica took to the hills with him. . . .

Tatica didn’t like Catholicism, she was very superstitious and believed in life after death. I remember what my grandmother used to say about Africans who lived far away from their countries. She said their spirits returned to their lands when they died. I couldn’t go to her funeral because I didn’t live in La Maya anymore. . . . I cried so much! But when I calmed down and closed my eyes I seemed to see her rise up to the sky and fly through the clouds, on the way back to her native land, towards her beloved, never forgotten Africa, which I learned to love too from all the stories she told us.”

The 1912 Afro-

“Many people gathered in my uncle’s house. They’d get me to stand guard at the door; they’d shut themselves into the little room off the patio where they kept the things for making candies. One day several men came, among them Pedro Ivonet and Evaristo Estenoz. When my aunt Mangá went to greet them, Estenoz put his arm around me and kissed me. Ivonet too; Estenoz was very handsome. There was another one, another handsome black man — I can’t remember his name — who made speeches; he spoke beautifully.

Back then I didn’t know how important they were in the movement. They were leaders of the Independent Coloured Party; but I had heard that a senator called Morúa Delgado had voted in a law against the creation of political parties for blacks, or rather, for people of only one race. ‘Coloured’ people considered this law unjust, because they realized they needed a political organization that would allow them to look for their own solutions to problems, because the white ones weren’t helping at all. . . . Estenoz met with the President of the Republic, who said he’d support them in gaining this right, that they should pretend to take up arms against the government so he could get the Assembly and the Senate to believe there would be war between blacks and whites and to avoid it they must vote down the Morúa law, and thus the Party would be approved.

[President Gómez’s] real interest lay in securing the black vote, because he wanted to be re-

Just imagine! How were they to defend themselves? With old shotguns? With machetes? Since they didn’t have enough weapons — and moreover they weren’t intending to wage war — they were hunted town and captured. Poor souls! I saw them when they brought them down from the hills, tied up. They killed them, threw them in pots and set them on fire. Many of those who surrendered were taken to a place called Arroyo Blanco and there they were murdered.”

Source: Maria de los Reyes Castillo Bueno, Reyita: The Life of a Black Cuban Woman in the Twentieth Century (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2000), pp. 23–

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- How does Reyita Castillo Bueno understand race?

- How does culture change for the different generations in Castillo Bueno’s narrative?

- How does Castillo Bueno convey the abolition of slavery and the wars of independence to readers?