The Fall of Imperial Russia

Imperial Russia in 1914 was still predominantly a rural and nonurbanized society. Russia came late to industrialization (see “The Modernization of Russia” in Chapter 24), and, although rapidly expanding, industrialization was still in its early stages. Peasants made up perhaps 80 percent of the population, although by 1914 a large number of these did seasonal work in the cities. To prevent peasant unrest, Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin (stal-EE-pihn) instituted agrarian reforms between 1906 and 1911 to replace the communal system of peasant land use with one that encouraged individual, private landownership. Stolypin hoped to create a class of politically conservative, capitalist farmers — an agrarian bourgeoisie. The permanent urban working class remained small, and many of these were simply commuters from the countryside. Besides the royal family and the nobility, Russian society consisted of the bourgeoisie (the elite, educated upper and middle classes, such as liberal politicians, propertied and professional classes, military officer corps, and landowners) and the proletariat (the popular masses, such as the urban working class, and rank-and-file soldiers and sailors). These two factions contended for power when the tsar abdicated in 1917.

Like their allies and their enemies, Russians embraced war with patriotic enthusiasm in 1914. At the Winter Palace, while kneeling throngs sang “God Save the Tsar,” Tsar Nicholas II (r. 1894–1917) vowed never to make peace as long as the enemy stood on Russian soil. For a moment Russia was united, but soon the war began to take its toll.

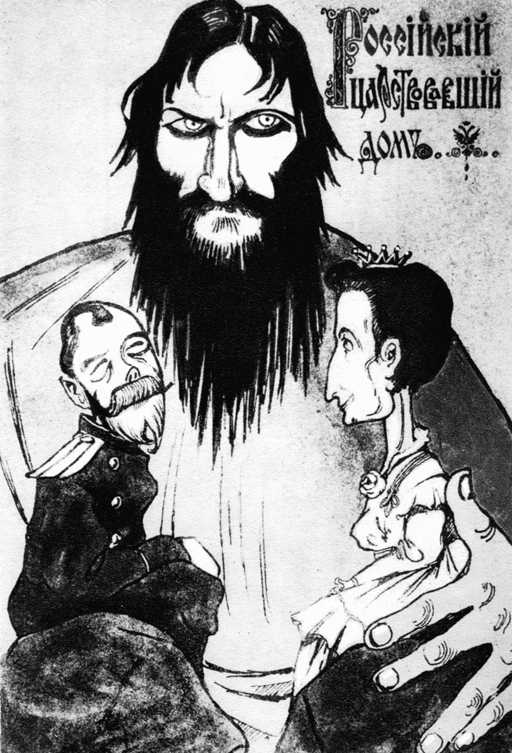

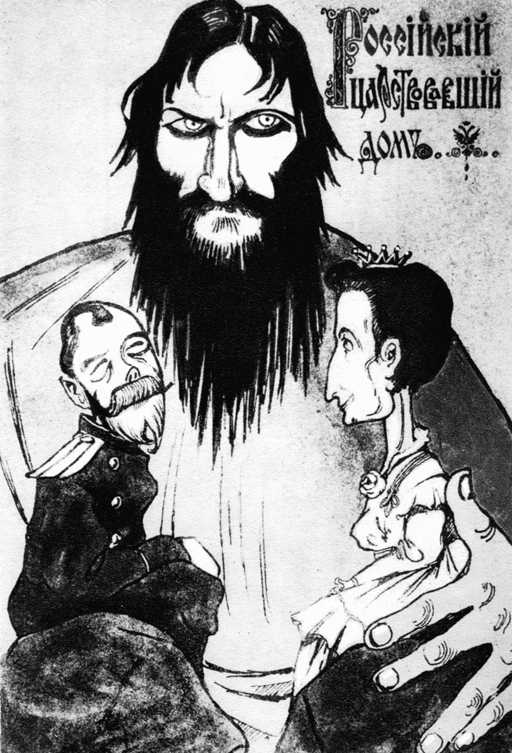

“The Russian Ruling House” This wartime cartoon captures the ominous, spellbinding power of Rasputin over Tsar Nicholas II and his wife, Alexandra. Rasputin’s manipulations disgusted the Russian public and contributed to the monarchy’s collapse. (© INTERFOTO/Alamy)

Unprecedented artillery barrages quickly exhausted Russia’s supplies of shells and ammunition, and better-equipped German armies inflicted terrible losses — 1.5 million casualties and nearly 1 million captured in 1915 alone. Russian soldiers were sent to the front without rifles; they were told to find their arms among the dead. The Duma, Russia’s lower house of parliament, and zemstvos (zemst-vohs), local governments, led the effort toward full mobilization on the home front. These efforts improved the military situation, but overall Russia mobilized less effectively for total war than did the other warring nations.

Although limited industrial capacity was a serious handicap in a war against highly industrialized Germany, Russia’s real problem was leadership. Under the constitution resulting from the 1905 revolution (see “The Modernization of Russia” in Chapter 24), the tsar retained complete control over the bureaucracy and the army. A kindly, slightly dull-witted man, Nicholas distrusted the moderate Duma and rejected popular involvement. As a result, the Duma, whose members came from the elite classes, and the popular masses became increasingly critical of the tsar’s leadership and the appalling direction of the war. In response, Nicholas (who had no military background) traveled to the front in September 1915 to lead Russia’s armies — and thereafter received all the blame for Russian losses.

His departure was a fatal turning point. His German-born wife, Tsarina Alexandra, took control of the government and the home front. She tried to rule absolutely in her husband’s absence with an uneducated Siberian preacher, Rasputin, as her most trusted adviser. Rasputin gained her trust by claiming he could stop the bleeding of her hemophiliac son, Alexei, heir to the throne. On November 1, 1916, opposition party leader Pavel Milyukov, speaking before the Duma, recounted the government’s failures and demanded, “Is this stupidity or is it treason?”9 In a desperate attempt to right the situation, three members of the high aristocracy murdered Rasputin in December 1916. In this atmosphere of unreality, the government slid steadily toward revolution.

Large-scale strikes, demonstrations, and protest marches were now commonplace, as were bread shortages. On March 8, 1917, a women’s bread march in Petrograd (formerly St. Petersburg) started riots, which spread throughout the city. While his ministers fled the city, the tsar ordered that peace be restored, but discipline broke down, and the soldiers and police joined the revolutionary crowd. The Duma declared a provisional government on March 12, 1917. Three days later, Nicholas abdicated.