Listening to the Past: C. L. R. James on Pan-African Liberation

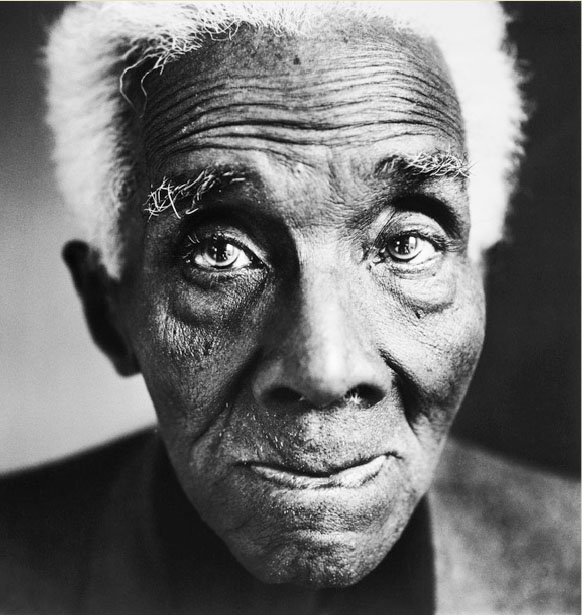

Trinidadian historian Cyril Lionel Robert James (1901–

Africa

“The dozen years that have unfolded since the winning of independence by the Gold Coast in 1957 are some of the most far-

They accepted the African leader and his African colleagues. But that is precisely why in African state after African state, with almost the rapidity with which independence was gained, military dictatorship after military dictatorship has succeeded to power. . . . What are the reasons for this rapid decay and decline of African nationalism? . . .

The states which the African nationalist leaders inherited were not in any sense African. With the disintegration of the political power of the imperialist states in Africa, and the rise of militancy of the African masses, a certain political pattern took shape. Nationalist political leaders built a following, they or their opponents gained support among the African civil servants who had administered the imperialist state, and the newly independent African state was little more than the old imperialist state only now administered and controlled by Black nationalists. That these men, western-

The United States

“Summer after summer has seen tremendous struggles by the Black masses, led by unknown, obscure, local leaders. Perhaps the most significant was that which followed the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, the world-

One can only record the question most often and most seriously asked: can any government mobilize the white population, or a great majority of it, in defence of white racism against militant Blacks? The only legitimate answer lies in the continuing militancy or retreat of the Black population. This population is at least 30 million in number, strategically situated in the heart of many of the most important cities in the United States. If the Black population continues to resist racism, the militants and youth actively and the middle classes sympathetic or neutral, then the physical defeat of the Black struggle against racism will involve the destruction of the United States as it has held together since 1776.”

Source: C. L. R. James, A History of Pan-

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- How does James explain the rise of military dictators in Africa?

- How does James equate the struggles in Africa and the United States?

- What does James mean when he says that a defeat in the civil rights struggle would mean the destruction of the United States?