Aryan Dominance in North India

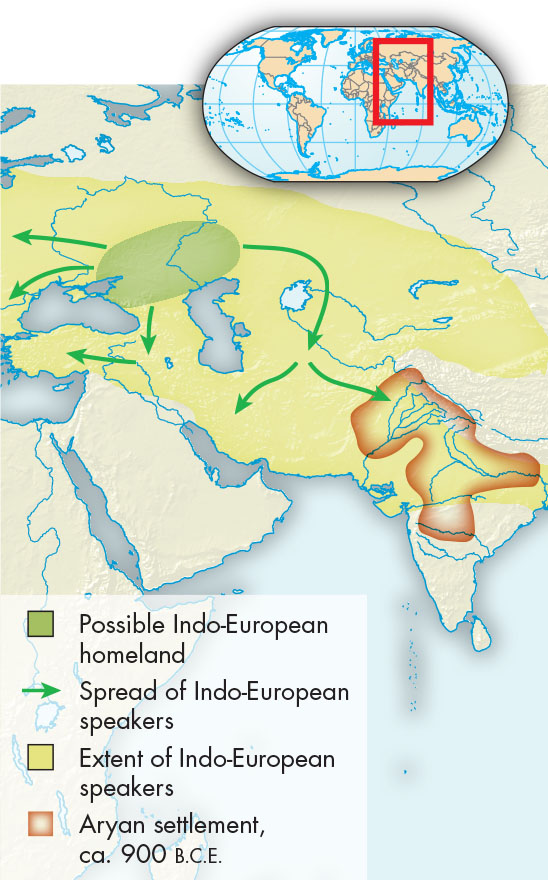

Until relatively recently, the dominant theory was that the Aryans came into India from outside, perhaps as part of the same movements of people that led to the Hittites occupying parts of Anatolia, the Achaeans entering Greece, and the Kassites conquering Sumer — all in the period from about 1900 B.C.E. to 1750 B.C.E. Some scholars, however, have proposed that the Indo-

Modern politics complicates analysis of the appearance of the Aryans and their role in India’s history. Europeans in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries developed the concept of Indo-

The central source of information on the early Aryans is the Rig Veda, the earliest of the Vedas, originally an oral collection of hymns, ritual texts, and philosophical treatises composed in Sanskrit between 1500 B.C.E. and 500 B.C.E. Like Homer’s epics in Greece, written in this same period (see “The Dark Age” in Chapter 5), these texts were transmitted orally and are in verse. The Rig Veda portrays the Aryans as warrior tribes who glorified military skill and heroism; loved to drink, hunt, race, and dance; and counted their wealth in cattle. The Aryans did not sweep across India in a quick campaign, nor were they a disciplined army led by one conqueror. Rather they were a collection of tribes that frequently fought with each other and only over the course of several centuries came to dominate north India. (See “Viewpoints 3.1: Divine Martial Prowess from the Rig Veda and the Epic of Gilgamesh.”)

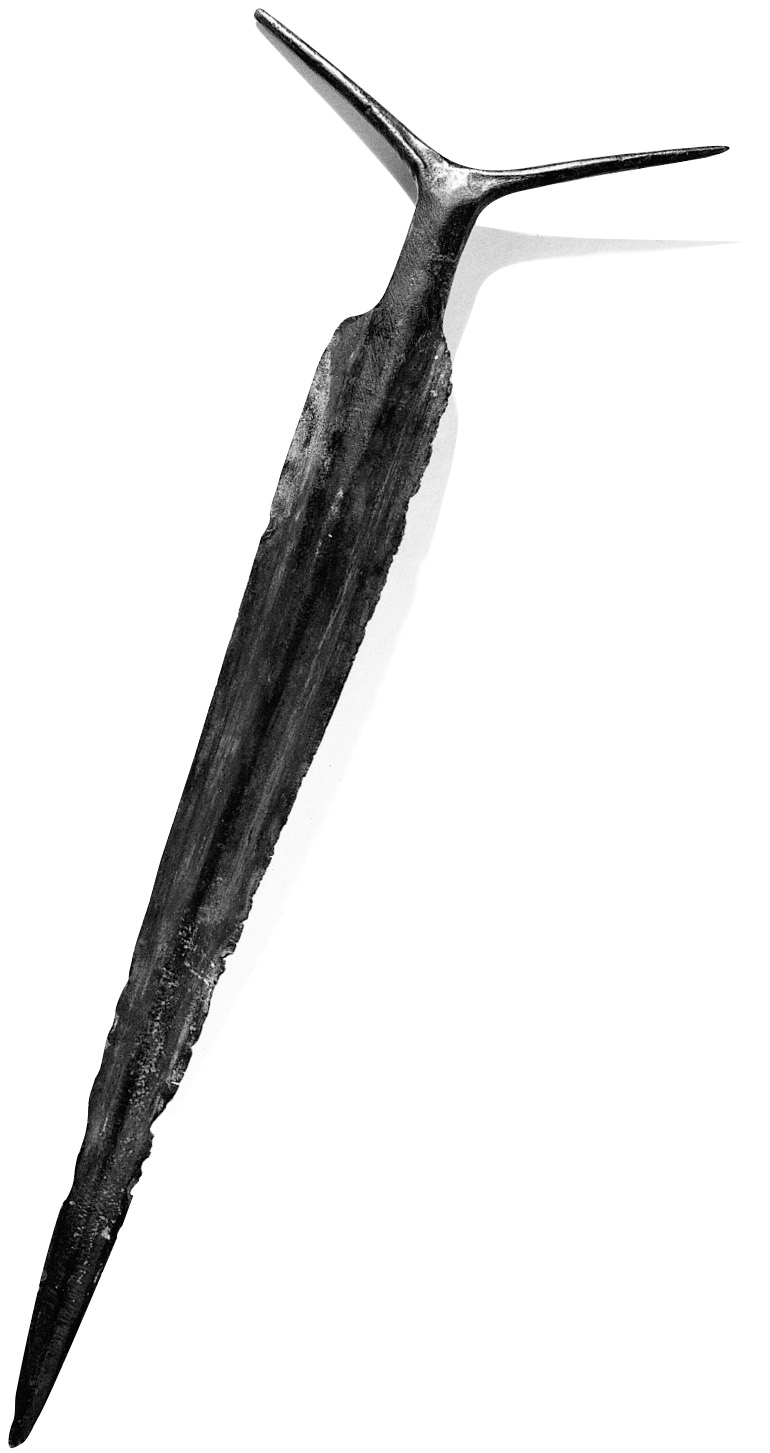

The key to the Aryans’ success probably lay in their superior military technology. Those they fought often lived in fortified towns and put up a strong defense against them, but Aryan warriors had superior technology, including two-

At the head of each Aryan tribe was a chief, or raja (RAH-

Over the course of several centuries, the Aryans pushed farther east into the valley of the Ganges River, at that time a land of thick jungle populated by aboriginal forest peoples. The tremendous challenge of clearing the jungle was made somewhat easier by the introduction of iron around 1000 B.C.E., probably by diffusion from Mesopotamia. (See “Global Trade: Iron.”) Iron made it possible to produce strong axes and knives relatively cheaply.

The Aryans did not gain dominance over the entire Indian subcontinent. South of the Vindhya range, people speaking Dravidian languages maintained their control. In the great Aryan epics the Ramayana and Mahabharata, the people of the south and Sri Lanka are spoken of as dark-

As Aryan rulers came to dominate large settled populations, the style of political organization changed from tribal chieftainship to territorial kingship. In other words, the ruler now controlled an area with people living in permanent settlements, not a nomadic tribe that moved as a group. Moreover, kings no longer needed to be elected by the tribe; it was enough to be invested by priests and to perform the splendid royal ceremonies they designed. The priests, or Brahmins, supported the growth of royal power in return for royal confirmation of their own power and status. The Brahmins also served as advisers to the kings. In the face of this royal-