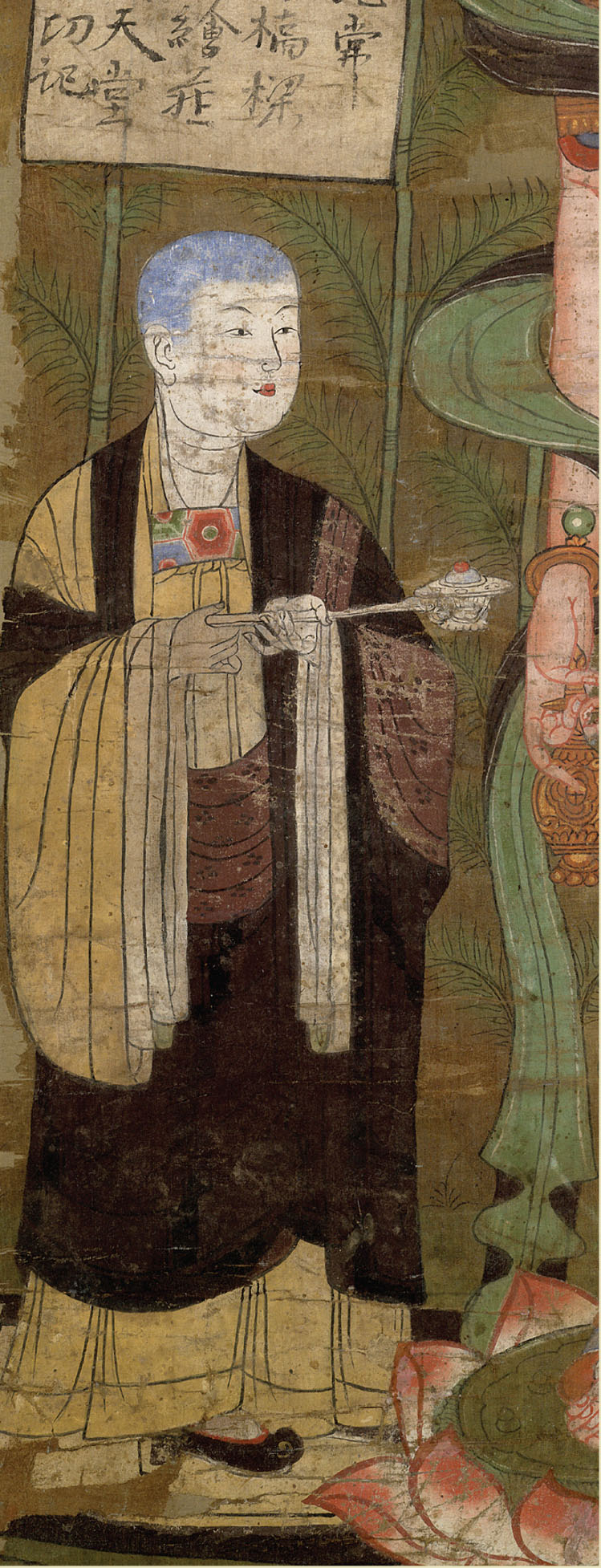

Listening to the Past: Sixth-Century Biographies of Buddhist Nuns

Women drawn to Buddhism could leave secular life to become nuns. Most nuns lived with other nuns in convents, but they could also work to spread Buddhist teachings outside the cloister. The first collection of biographies of eminent nuns in China was written in 516. Among the sixty-

Kang Minggan

“Minggan’s secular surname was Zhu, and her family was from Kaoping. For generations the family had venerated the [Buddhist] teachings known as the Great Vehicle.

A bandit who wanted to make her his wife abducted her, but, even though she suffered increasing torment, she vowed not to give in to him. She was forced to serve as a shepherdess far from her native home. Ten years went by and her longing for her home and family grew more and more intense, but there seemed to be no way back. During all this she kept her mind fixed on the Three Treasures, and she herself wished to become a nun.

One day she happened to meet a Buddhist monk, and she asked him to bestow on her the five fundamental precepts [of a Buddhist householder]. He granted her request and also presented her with a copy of the Bodhisattva Guanshiyin Scripture, which she then practiced chanting day and night without pause.

Deciding to return home to build a five-

As Minggan approached old age, her moral cultivation was even more strict and lofty. All the men and women north of the Yangtze River honored her as their spiritual teacher in whom they could take refuge.

In the spring of 348 of the Jin dynasty, she, together with Huichan and others — ten in all — traveled south, crossed the Yangtze River, and went to see the minister of public works, He Chong, in the capital of the Eastern Jin dynasty. As soon as he met them, he showed them great respect. Because at that time there were no convents in the capital region He Chong converted one of his private residences into a convent for them.

He asked Minggan, “What should the convent be named?”

She replied, “In the great realm of the Jin dynasty all the four Buddhist assemblies of monks, nuns, and male and female householders are now established for the first time. Furthermore, that which you as donor have established will bestow blessings and merit. Therefore, let us call the convent ‘Establishing Blessings Convent.’” He Chong agreed to her suggestion. Not long afterward Minggan took sick and died.”

Daoqiong

“Daoqiong’s secular surname was Jiang. Her family was from Danyang. When she was a little more than ten years old, she was already well educated in the classics and history, and after her full admission to the monastic assembly she became learned in the Buddhist writings as well and also diligently cultivated a life of asceticism. In the Taiyuan reign period [376–

In 431 she had many Buddhist images made and placed them everywhere: in Pengcheng Monastery, two gold Buddha images with a curtained dais and all accessories; in Pottery Office Monastery, a processional image of Maitreya, the future Buddha, with a jeweled umbrella and pendants; in Southern Establishing Joy Monastery, two gold images with various articles, banners, and canopies. In Establishing Blessings Convent, she had an image of the reclining Buddha made, as well as a hall to house it. She also had a processional image of the bodhisattva, Puxian [or Samantabhadra], made. Of all these items, there was none that was not extremely beautiful. Again, in 438, Daoqiong commissioned a gold Amitayus [or Infinite Life] Buddha, and in the fourth month and tenth day of that same year a golden light shone forth from the mark between the eyebrows of the image and filled the entire convent. The news of this event spread among religious and worldly alike, and all came to pay honor, and, gazing at the unearthly brilliance, there was none who was not filled with great happiness. Further, using the materials bequeathed to her by the Yuan empress consort, she extended the convent to the south to build another meditation hall.”

Daozong

“Daozong, whose family origins are unknown, lived in Three-

On the full-

Source: Kathryn Ann Tsai, trans., Lives of the Nuns: Biographies of Chinese Buddhist Nuns from the Fourth to Sixth Centuries. Copyright © 1994 University of Hawai‘i Press. Reprinted with permission of the University of Hawai‘i Press.

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- Why were the lives of these three particular nuns considered worth recording? What was admirable or inspiring about their examples?

- What do the nuns’ spiritual journeys reveal about the virtues associated with Buddhist monastic life?

- Do you see a gender element in these accounts? Were the traits that made a nun admirable also appropriate for monks?