The Qin Unification, 221–206 B.C.E.

In 221 B.C.E., after decades of constant warfare, Qin (chin), the state that had adopted Legalist policies during the Warring States Period (see “Legalism” in Chapter 4), succeeded in defeating the last of its rivals, and China was unified for the first time in many centuries. Deciding that the title “king” was not grand enough, the king of Qin invented the title “emperor” (huangdi). He called himself the First Emperor (Shihuangdi) in anticipation of a long line of successors. His state, however, did not long outlast him.

Once he ruled all of China, the First Emperor and his shrewd Legalist minister Li Si embarked on a sweeping program of centralization that touched the lives of nearly everyone in China. To cripple the nobility of the defunct states, who could have posed serious threats, the First Emperor ordered the nobles to leave their lands and move to the capital. The private possession of arms was outlawed to make it more difficult for subjects to rebel. The First Emperor dispatched officials to administer the territory that had been conquered and controlled the officials through a long list of regulations, reporting requirements, and penalties for inadequate performance. These officials owed their power and positions entirely to the favor of the emperor and had no hereditary rights to their offices.

To harness the enormous human resources of his people, the First Emperor ordered a census of the population. Census information helped the imperial bureaucracy to plan its activities: to estimate the cost of public works, the tax revenues needed to pay for them, and the labor force available for military service and building projects. To make it easier to administer all regions uniformly, the Chinese script was standardized, outlawing regional variations in the ways words were written. The First Emperor also standardized weights, measures, coinage, and even the axle lengths of carts (important because roads became deeply rutted from carts’ wheels). To make it easier for Qin armies to move rapidly, thousands of miles of roads were built. Good roads indirectly facilitated trade. Most of the labor on the projects came from drafted farmers or convicts working out their sentences.

Some modern Chinese historians have glorified the First Emperor as a bold conqueror who let no obstacle stop him, but the traditional evaluation was almost entirely negative. For centuries Chinese historians castigated him as a cruel, arbitrary, impetuous, suspicious, and superstitious megalomaniac. Hundreds of thousands of subjects were drafted to build the Great Wall (ca. 230–

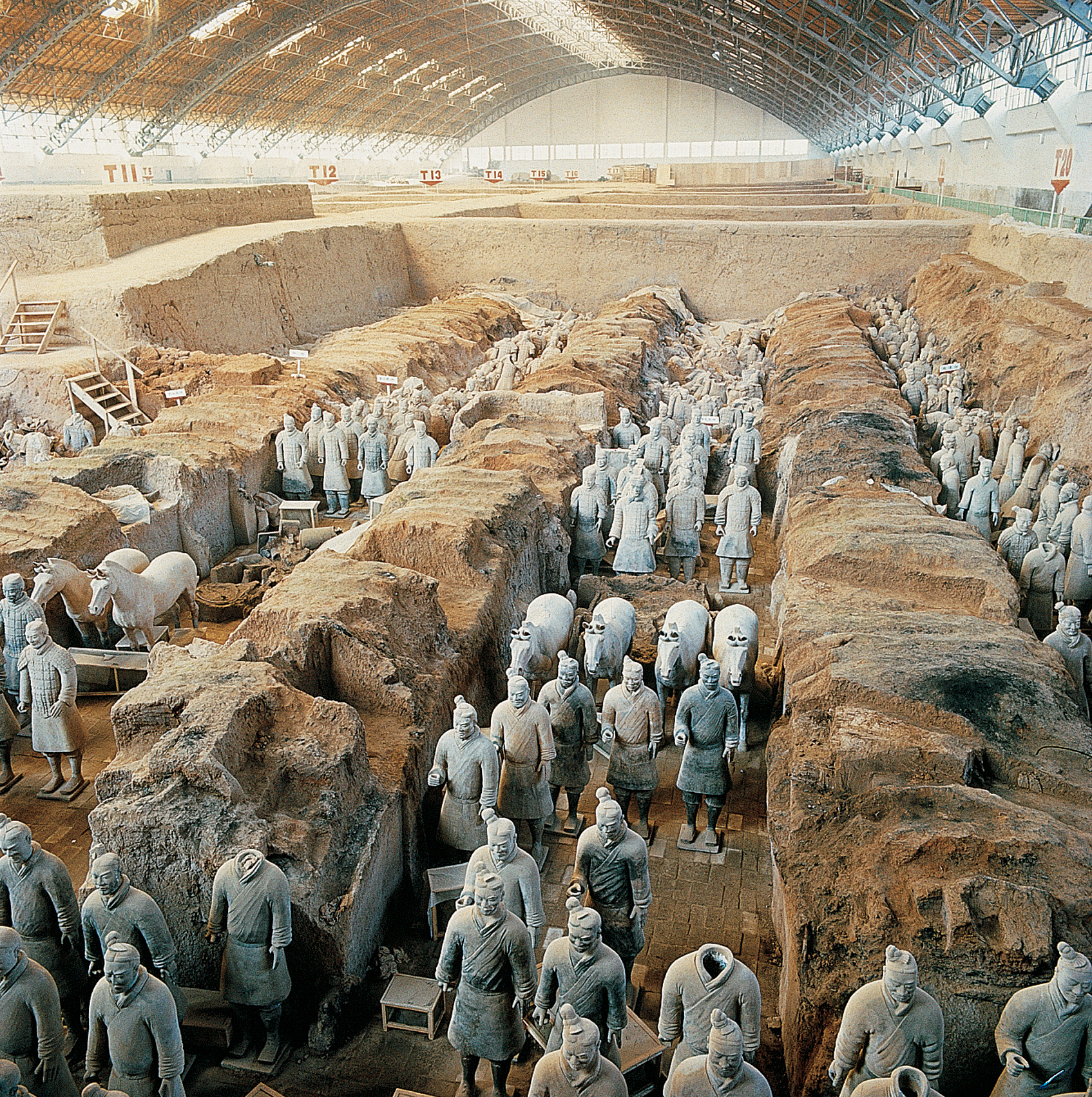

Assassins tried to kill the First Emperor three times, and perhaps as a consequence he became obsessed with discovering the secrets of immortality. He spent lavishly on a tomb designed to protect him in the afterlife. Although the central chambers have not yet been excavated, in nearby pits archaeologists have unearthed thousands of life-

Like Ashoka in India a few decades earlier (see “The Reign of Ashoka, ca. 269-232 B.C.E.” in Chapter 3), the First Emperor erected many stone inscriptions to inform his subjects of his goals and accomplishments. He had none of Ashoka’s modesty, however. On one stone he described the conquest of the other states this way:

The six states, insatiable and perverse, would not make an end of slaughter, until, pitying the people, the emperor sent troops to punish the wicked and display his might. His penalties were just, his actions true, his power spread far, all submitted to his rule. He wiped out tyrants, rescued the common people, brought peace to the four corners of the earth. His enlightened laws spread far and wide as examples to All Under Heaven until the end of time. Great is he indeed! The whole universe obeys his sagacious will; his subjects praise his achievements and have asked to inscribe them on stone for posterity.1

After the First Emperor died in 210 B.C.E., the Qin state unraveled. The Legalist institutions designed to concentrate power in the hands of the ruler made the stability of the government dependent on his strength and character, and his heir proved ineffective. The heir was murdered by his younger brother, and uprisings soon followed.